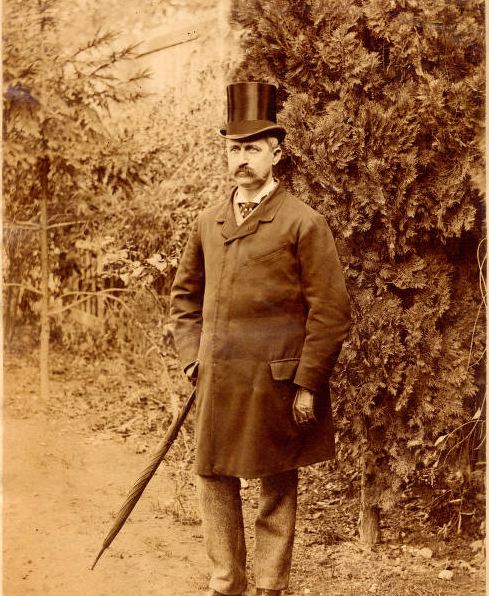

Julius LeBlanc Stewart, whose work I discovered via Femme Femme Femme, was an American artist who studied and worked mostly in Europe. He was a pupil of Jean-Léon Gérôme and Raimundo de Madrazo. He absorbed Gérôme's technical skills, to a degree, but generally followed de Madrazo in his choice of subjects, contemporary interiors and portraits, mostly of women, that usually featured a sensual treatment of fabrics. These portraits remind one strongly of John Singer Sargent's and are often very fine:

Stewart, like Sargent, was a late Victorian — he lived until 1919 — and like Sargent was attracted to the free brush-strokes of the Impressionists, always allied, however, with a rigorous academic draftsmanship and a concern for the evocation of space for dramatic effects.

Like many Victorian academic painters, Stewart sketched very freely, with an eye to the surface effects of paint on canvas, preserved in a limited way in the more finished work he exhibited. Degas struck a different balance between sketch and “finish”, but the dynamic was exactly the same. Below is a Stewart sketch:

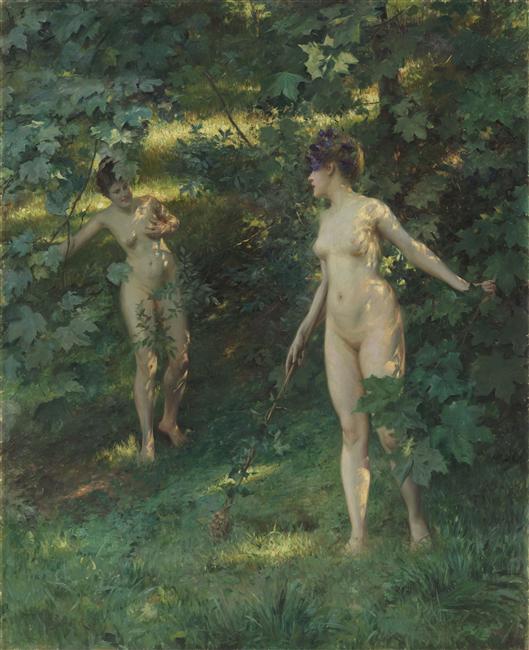

He did a series of nudes in outdoor settings that evoked mythological subjects, but only nominally. They have the frankness and the contemporary feel of Anders Zorn's very similar scenes:

Like Tissot, Stewart loved the spatial dramatics of figures on ships, as with the painting at the head of this post.

The late Victorians influenced by Impressionism but still not seduced away from academic formalism constitute a fascinating group, though Sargent is the only one of them who has any kind of reputation today, alas.