A classic strip by George McManus, delightfully drawn and sometimes very funny.

Monthly Archives: March 2009

THE STORIES OF WOMEN

The stories of women go unheard, I heard her to say, Lila.

“No one knows what happens to women. No one knows how bad it is, or how good it is, either. Women can’t talk — we know too much.”

From the short story “Ceil” by Harold Brodkey, published in The New Yorker, 1983.

[Image: “Venus Rising From the Sea — A Deception”, by Raphaelle Peale, 1822.]

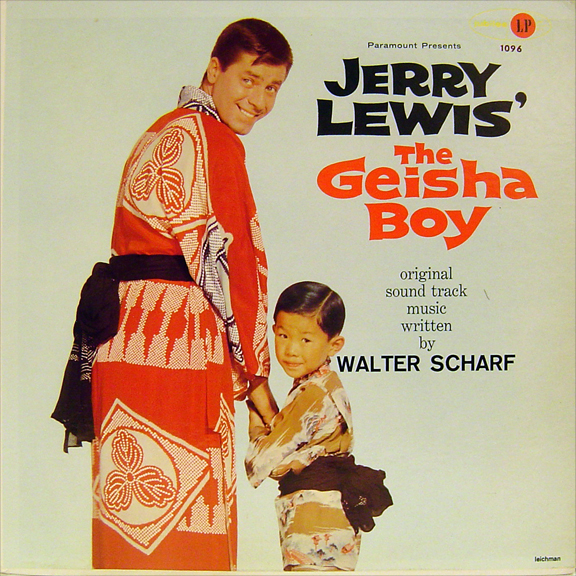

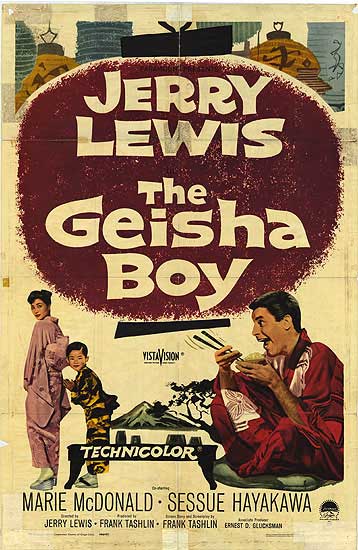

JERRY LEWIS, FRANK TASHLIN AND GOD (OH, MY!)

Religiosity in 20th-Century art has been a problematic subject for mainstream intellectual critics, unless it could be given a negative twist, treated as a form of neurosis — Hitchcock's “Catholic guilt” being a prime example. This leaves many aspects of many artists' work unexamined.

mardecortesbaja welcomes ventures into problematic subjects and therefore presents without further ado a post about explicit religiosity in the films of Jerry Lewis, written by my friend and fellow film buff P. F. M. Zahl:

Jerry Lewis is often accused of sentimentality, of embarrassing sentimentality, in relation to the films he made in his classic period.

The sentimentality is in massive evidence within The Family Jewels (1965), in which a poor little rich girl who has been orphaned is required to choose her new 'father' from among her eccentric uncles. Lewis plays them all, or over-plays them all. Yet I defy you to not wipe away a tear at the conclusion of the movie, when the nature of her chosen 'father's' sacrificial love comes out. I defy you not to be moved. Even after you have winced through two hours of hammering slapstick.

The God question in Lewis is even more fraught than the question of his sentimentality. I'm not sure that even the French can handle this one.

I am thinking of two of the main Jerry Lewis movies that were written and directed by Frank Tashlin. Tashlin, or “Tash”, as Lewis called him, taught his more famous student 'everything I ever learned' about movie-making, and then Jerry took it from there. But to much contemporary sensibility — today, that is — the God factor in two films, The Disorderly Orderly (above, 1964) and The Geisha Boy (1958) is just too hot to handle. And I am not even going to mention Who's Minding the Store? (1963), with its “We're Sorry” denouement written touchingly on the placards that all the lead characters wear as they plead for Jerry to forgive them. Nor will I mention Rock a Bye Baby (1958), with its soaring Grace on the part of the devastatingly unselfish TV repairman (Lewis) who brings up someone else's baby triplets alone.

In The Disorderly Orderly Jerry prays fervently for an old girlfriend, who did once spurn him and continues to spurn him, when she is brought into the emergency room after an almost successful attempt at suicide. Then when she recovers, Jerry prays again — and overdoes it a little — to God, thanking God for answering his prayer. He then proceeds to basically redeem this selfish but also hurt woman, winning her affection in a most 'Christian' manner, if I could put it that way. Every time I show The Disorderly Orderly to a group, the whole place dissolves at the end. And that's almost 50 years after it was made.

To be noted is Frank Tashlin's religion, which he by no means wore on his sleeve and would probably never have referred to. But we also know that “Tash” wrote and directed a short animated film for the Lutheran Church in 1949 entitled The Way of Peace, which is as explicit a Christian warning concerning nuclear war as ever was filmed during that era in Hollywood. This religious short subject had disappeared, and I had the privilege two years ago of bringing it back to the surface from the ELCA (i.e., Evangelical Lutheran Church in America) archives. I believe it can now be YouTubed. In any case, The Way of Peace is an important clue to Frank Tashlin's religious views. [Editor's note: I've written about The Way Of Peace previously, here.]

But it is The Geisha Boy where Jerry and God connect at the most length. Jerry stars as The Great Wooley, a magician on tour with the USO in occupied Japan. He charms a little boy whose parents are both dead and who has not smiled or laughed for five years. Jerry and little Mitsuo connect, and Mitsuo tells Jerry that he is the answer to his prayers. Jerry is moved, comments, and tells Suzanne Pleshette. Jerry then goes to Korea and performs for the GI's, taking time, in a sustained and extremely pointed scene, to pray before an altar — a sort of makeshift battlefield altar — for the little boy back in Japan. Prayer is referred to again, and finally The Great Wooley adopts the boy, takes him (together with his Japanese aunt, whom he marries) back to America, and all three become a happy family magic act. It is not actually all that maudlin.

As someone who believes in prayer, and who sure believes in reconciliation between previously estranged people, I find The Geisha Boy moving and also full of love. Plus, the Technicolor palette is out of sight, from the first shot to the last.

I would even go so far as to 'pair' The Geisha Boy with Kurosawa's Ikiru because they relate to the exact same period in the history of Japan, and in The Geisha Boy the little boy's last name is Watanabe; and as we all know, the hero of Ikiru is named Watanabe. In fact, the 'son' character in Ikiru is named Mitsuo Watanabe and the 'son' character in The Geisha Boy is named Mitsuo Watanabl. You can't convince me that Taslin hadn't seen Ikiru, especially when you hear Kurosawa report that it took them two full weeks to come up with the unusual 'Watanabe' name for the hero of that great classic of world cinema.

Jerry Lewis and God. Jerry Lewis and Frank Tashlin and God. Or maybe it was just the Fifties and early Sixties. But watch for God to appear within the Lewis canon. I also think He's still there, in the telethons. I see God pop up in the telethons all the time. I also know that Lewis, right in the heart of his heyday, treasured above all awards, above all European honors and medals, an award he received from the State of Israel. If you don't think God is friends with Jerry Lewis, then look again. Oh, and note the Buddhist tie-in, too, within The Geisha Boy, in the thumping importance given to the character of Harry the Hare. I don't think that's a coincidence either.

mardecortesbaja would just like to add that it's common, but hardly quite responsible, intellectually speaking, to admire Tashlin and Lewis for their radical dislocations of cinematic convention and their radical critiques of American society and to ignore the spiritual values (or the spiritual sentimentality, if you prefer) which also informs their work. You have ask, was the spiritual dimension an embarrassing aberration in that work, or one of the key sources of its radical attitudes? See my post on The Way Of Peace for further thoughts on this subject, especially as it relates to Tashlin.

THE FUNNY PAPERS: LITTLE NEMO, 1924

The final panel from a Sunday page published in 1924.

THE RIVER (1929)

Frank Borzage's The River is a turbid erotic fairytale about a boy-man and a “fallen woman” who awakens him sexually and is in turn saved by his innocence.

It's a film uncharacteristic of Hollywood in that its sensuality is both frank and serious — it takes adult sexuality as a given and presents it without the adolescent leer and snicker or the aura of the exotic which usually accompany erotic idylls in American cinema. In this film, Huck Finn meets Sadie Thompson at a dam construction site and learns about currents more treacherous than the Mississippi's.

The River stars Charles Farrell and Mary Duncan, who would be re-teamed a year later in Murnau's City Girl (above) — a very different kind of film, reviewed earlier here. Murnau, for all the poetic imagery in City Girl, was trying to create a more naturalistic atmosphere than he had in Sunrise — it was a break from his characteristic expressionism, an attempt to situate the story in a recognizably American context, as opposed to the mythic, vaguely European storybook environment of Sunrise.

The setting of The River isn't quite European but it's fantastic — the construction camp, with its tiers of workers' cabin jacked up on stilts on the side of a mountain, looks like something from Middle Earth. The narrative has a feverish, dreamlike tone which accords with its odd setting. One might link it to the home-grown American expressionism of Hawthorne and Poe, minus the high-Gothic spookiness.

Mary Duncan gives an extraordinary performance, as she does in City Girl — perfectly conveying a raunchy kind of lust mixed with cynicism mixed with a longing for something she can believe in. She's very sexy and very touching at the same time, much as Swanson was in Sadie Thompson. Farrell's mixture of naivete and virility is almost as impressive.

The plot of The River gets wildly melodramatic but the movie doesn't feel exactly like a melodrama — everything reads as metaphor, never to be taken quite literally. Farrell chopping down tall lumber to relieve his sexual frustration, nearly freezing to death in a snowstorm before Duncan's body heat restores him to life — it's all about sex and not much else.

Only one print of the film has survived and it's incomplete, missing a few early scenes and the whole last reel. The version on the recent Murnau, Borzage and Fox box set is a reconstruction using production stills and intertitles derived from the script to fill in the gaps. The loss of the last reel is very frustrating — one is desperate to know if Borzage was able to give the final action sequence the climactic excitement and release the tale demands.

We are left with a fragment (about half) of a minor masterpiece of the silent screen and one of the most original erotic reveries in all of cinema.

THE FUNNY PAPERS: LITTLE NEMO, 1924

The penultimate panel from a Sunday page published in 1924 — final panel coming soon!

CATCHING UP WITH JERRY LEWIS

Matt Barry, over at The Art and Culture Of Movies, has just posted a superb appreciation of Jerry Lewis's films, pointing out the indisputable (and somewhat depressing) truth that they're still way ahead of their time . . . that modern movie comedies rarely evince half the daring and originality of the ones Lewis was making forty years ago.

THE FUNNY PAPERS: LITTLE NEMO, 1924

The fifth panel from a Sunday page published in 1924 — curiouser and curiouser. Successive panels to follow!

EARLY MURNAU

This month, Kino is releasing two early Murnau films that haven't been available on DVD before in this country — The Haunted Castle (from 1921) and The Finances Of the Grand Duke (from 1924). Here are reviews of both films:

THE HAUNTED CASTLE

Murnau made radically diverse kinds of films in the early Twenties — still feeling his way as filmmaker. In The Haunted Castle we see him at his most conventional — and least interesting. The film is

a cheesy melodrama based on a magazine story. It is exceptionally

well-designed and carefully photographed, in something resembling a

“studio style” — handsome, elegant, tasteful, uninspired.

On its face the tale is a kind of simple-minded Agatha Christie-type

murder mystery in which a gang of aristocrats assembles at a country

estate for a hunting weekend and dire secrets are exposed. There's a

monk among the party, whose tragically unconvincing tonsure appliance

immediately gives away the climactic gag involving assumed identity.

On the other hand, the impeccable interior sets, the graceful if

unimaginative mise-en-scène, the generally excellent acting and the

occasional flights of visual fancy give the production a weight which

the story can't begin to support. The mood and pace of the film evoke The Rules Of the Game even as the narrative evokes The Old Dark

House. Ultimately it has the feel of an assignment — or a

demonstration piece in which Murnau proved he could deliver a classy, conventional,

“well-made” commercial product.

As usual when Murnau moves outdoors, there are beautiful images of the

countryside — always involving a dynamic spatial dimension . . . not

just pretty pictures of pretty places but images of a geography

penetrated and revealed by carefully choreographed movement though its space. There are some sweet and

lyrical and memorable images illustrating a flashback to the halcyon

days of a marriage that went very wrong.

And there is one goofy interpolation which alone feels like Murnau being

Murnau. A kitchen assistant gets hold of a bag of whipped cream and

violates it with antic lust — thrusting two fingers deep into the bag

and then thrusting the fingers deep into his mouth. Later, the boy

dreams of having another crack at the cream, this time with the monk

standing over him approvingly and sanctioning his delight as the boy

takes a slurp of cream and then slaps the head cook who scolded him for

stealing it in real life. There's a gleeful homoerotic aspect to the

gag and a tone which violates the grave hokum of the rest of the film.

THE FINANCES OF THE GRAND DUKE

In The Finances Of the Grand Duke, a much

more confident Murnau expands on the juvenile glee of the whipped cream

gag and makes a whole fluffy dessert out of it. A tiny island Duchy is

about to go bankrupt — the carefree Grand Duke has a hard time taking

the crisis seriously. He prefers throwing the last coins remaining from

his fortune into the ocean for a group of half-naked boys to dive

after.

Salvation appears in the form of a speculator who wants to buy

part of the island in order to exploit the sulfur deposits there. The

Grand Duke imagines his subjects fainting from the fumes — but really

what disturbs him, we know, is the sheer bad taste of the thing . . .

the simply awful smell. A rich Russian Grand Duchess, who doesn't

actually know the Grand Duke but has heard good things about him,

offers salvation of a different kind, if only she can escape her

brother, trying to track her down before she can offer herself in marriage to the penniless

sovereign.

Meanwhile the speculator has concocted a rebellion among the

subjects of the island, with the aid of four scoundrels, one of whom is

played by Max Schreck. Without the Nosferatu make-up and with a full

head of hair, and with a charming dumb smile, he looks quite human and

harmless — a burlesque version of Max Von Sydow.

The silliness multiplies exponentially and all comes right in the end,

of course, and the result is a real little jewel of a movie, with a

very distinctive tone — juvenile in spirit but visually elegant,

feckless but good-hearted, frothy but really funny, too. (It played

wonderfully in the crowded theater where I first saw it, with genuine happy laughter — as

opposed to “knowing” film-buff chortles — throughout.)

Here is Richard Ellman on Oscar Wilde, from his magisterial biography

of the writer: “As for his wit, its balance was more hazardously

maintained than is realized. Although it lays claim to arrogance, it

seeks to please us. Of all writers, Wilde was perhaps the best company.

Always endangered, he laughs at his plight, and on his way to the loss

of everything he jollies society for being so much harsher than he is,

so much less graceful, so much less attractive.”

One can't help seeing Murnau in the Grand Duke of this film — the

director bedeviled by the money men, the homosexual threatened by

exposure, by the loss of everything, yet so sure of himself, of his

genius, so exhilarated by life and the energy of creation that he just

can't take the grim side of things too seriously.

The sheer joy that radiates throughout this movie — the joy in

filmmaking, the joy in beautiful places (like the gorgeous Dalmation

coast locations where the film was shot), the joy of watching people

and ships and waves inhabit and transform space — is finally very

moving. We rarely get to share this aspect of genius, which is usually

engaged in weightier endeavors. This movie is weightless — like a

helium balloon — and it's marvelous to watch it rise up and disappear

into nothingness.

The films will be available separately from Kino or as part of a box set with a new edition of Faust and previously released versions of Nosferatu, The Last Laugh and Tartuffe. I haven't seen the Kino versions of the new titles but I'm looking forward to checking them out and you should be, too. I mean, it's Murnau.

THE FUNNY PAPERS: LITTLE NEMO, 1924

The fourth panel from a Sunday page published in 1924 — successive panels to follow!

THE CRUNCH

Last November I predicted that the stock market would bottom out somewhere between five and six thousand points. It looks as though we'll be there soon — the Dow closed today below seven thousand for the first time in almost twelve years. I also said that once the Dow dropped below six thousand it would probably rebound to slightly above six thousand and hover there until a general economic recovery kicked in.

The Dow belongs at just above six thousand, since that's where it was before the high-tech bubble, followed by the real-estate bubble, inflated the value of stocks irrationally.

At the same time, though, I predicted that if the Dow dropped below five thousand, which remains a possibility, it would signal a total collapse of confidence in the system and its ability to recover. This would probably lead to a worldwide panic, plunging us into a catastrophic depression from which we would not emerge for decades.

In other words, it's crunch time — a favorable moment, perhaps, to stock up on canned goods and gather a supply of cash or, better still, gold, for a potential emergency.

THE FUNNY PAPERS: LITTLE NEMO, 1924

The third panel from a Sunday page published in 1924 — successive pages to follow!

THE FUNNY PAPERS: LITTLE NEMO, 1924

The second panel from a Sunday page published in 1924 — successive panels to follow!