Edna Ferber's Show Boat isn't a great novel but it's great fun — a good story told in a lively way.

It's easy to see, too, why it appealed to Oscar Hammerstein II and Jerome Kern as material for a musical play. It's a book infused with a sentimental love for theater and nostalgia for the romance of its bygone days.

The era of the show boat, coming to an end when Ferber published the book in 1926, is presented as a kind of lost Eden of American show business, somehow magically recovered by modern performers who remember the old ways.

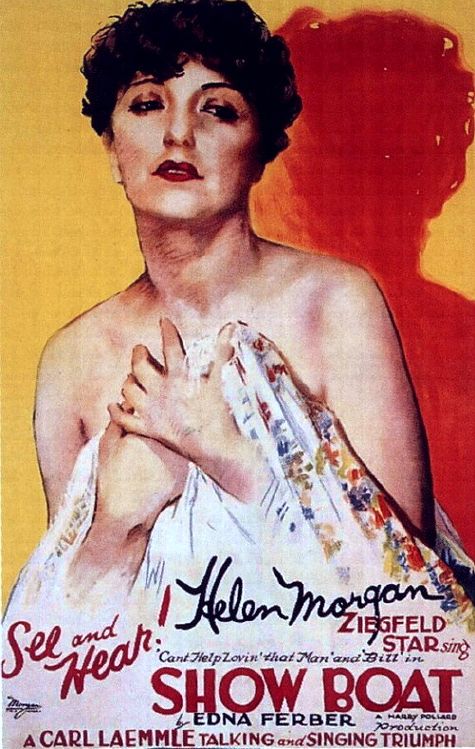

It also deals quite explicitly with the most crucial but often disguised conversation at the heart of American popular entertainment — that between whites and blacks. (Above is a portrait of Jules Bledsoe, the stage musical's original Joe.) Ferber is sensitive to the dynamic quality of this conversation and also to the injustice and hypocrisy that inform it. Julie Dozier, the actress of mixed race expelled from the Eden of Captain Andy's Cotton Blossom, is both an emotional and theatrical inspiration to the novel's (white) female protagonist, Magnolia Hawks. It is only race that condemns Julie, along with all African-American performers, to a life on the margins of show business, and Ferber's book bristles with outrage over this. (The poster below features Helen Morgan, the stage musical's original Julie, who reprised her role in the 1929 part-talkie film version.)

Hammerstein and Kern, like most show folk, were clearly sentimental about “the business”, and like most lovers of American music, they were both inspired and instructed by black musical culture. It remains astonishing, some eighty years on, that they had the ambition to deal with these themes in such a mature and serious way in their stage production of Show Boat. It was ahead of its time in 1927, and in some ways it remains ahead of our time, too.

Kern's music, of course, exists outside of time, and would have been a miracle in any age.