A second report from a recent cultural pilgrimage to New York by Paul

Zahl:

They were all broadcast at nine-thirty, Friday nights on CBS, starting

in March of 1961, right before The Twilight Zone.

I'm referring to the insanely scary episodes of Roald Dahl's

short-lived television series entitled Way Out.

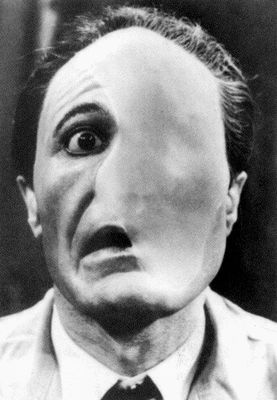

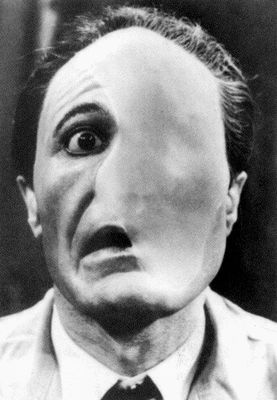

[That's Dahl above, about six years before he did Way Out.]

Do you remember them?

They were grisly, brief, almost always with surprising and shocking

endings, and made a huge impression on watchers of any age.

When I compare the impact of Way Out to The Outer Limits, which was

great, and The Twilight Zone, which was greater . . .

. . . Way Out wins the race.

There was not one single element of humor, except that of the henpecked

or cuckolded, and therefore vengeful, husband — a frequent theme.

The music, by Robert Cobert — who would later do Dark Shadows, Kolchak the Night Stalker, and all the Dan Curtis productions of the

1970s — was extremely eerie.

And Dick Smith, who went on to become a Hollywood legend, did the

Gothic makeup jobs.

But the thing is, you can't see them! They're impossible to see.

They've never been officially released to DVD or video, although four,

and four only, are unofficially available in very poor video versions.

The reason they haven't been released involves some complicated rights

issues — but David Susskind, who produced the series, gave copies of

the shows to The Museum of Broadcasting in New York City, now known as

the Paley Media Center, on West 52nd Street.

It is only there that these shocking little segments of early Sixties

television can be viewed.

They can be viewed, however.

Last Thursday, after seeing Our Town at the Barrow Street Theatre the

night before, I went up to midtown and staked out a scholar's console

in the Library of the Paley Center.

I was able to watch four episodes of Way Out, all of which I had seen

in 1961, with a child's (haunted) eyes; and none of which I had seen

again since those unsettling Friday nights in Georgetown, D.C.

The one I was most interested in seeing was the scariest, at least

then, and is called “Soft Focus”.

“Soft Focus” is 29 minutes of Barry Morse playing a photographer who

has invented a retouching agent for his portraits of people, which has

the side effect of retouching their actual faces. Thus a little boy

loses an ugly birthmark which “Dr. Pell” has erased in the lab. Then,

too, an actress whose face has been scarred is able to be beautiful

again with the help of Dr. Pell. Dr. Pell's wife, however, Louise, is

involved with her husband's young assistant. Louise doesn't know that

her husband knows what is going on.

He begins to 'touch up' a photograph of her. She starts to age. (He

touches up his own photograph, too, to make himself look younger.) When she

begins to look about 50 or so — and she looks awful — her boyfriend

jilts her. Enraged and abandoned, she enters her husband's studio and

right in front of his eyes, pours the whole bottle of solution on his

portrait. He screams, and in the climax, which no one who saw it in

1961 ever forgot, he turns towards his gloating wife, and towards the

camera, with half his face wiped away, a perfect blank.

Dick Smith accomplished the effect perfectly. Barry Morse just stares

at you, the left side of his face a smooth nothing of putty.

“Soft Focus” was written by Phil Riesman, Jr., a prolific TV writer who

specialized in history-based shows but wrote three episodes of Way

Out. The basic idea of Reisman's script for “Soft Focus”, the

unrelenting evil of the villain's vengeance, and of his philandering

wife's vengeance in return, is completely uncompromised. The

television mise-en-scène is perfect, mostly closeups, with two long

shots, one to show that Dr. Pell knows about his wife's infidelity; and

the last shot of the show, viewing the screaming, flailing, helpless

victim of his own wrath in shadow, shadow, shadow.

There is no moral or religious significance to “Soft Focus”, nor to

any of the Way Out teleplays — and I am interested in finding such

significance when I can. “Soft Focus” is a completely shattering use

of the small screen to horrify and make an indelible impression on the

viewer, again of any age.

Take the time to visit the Paley Media Center on the north side of

52nd Street between Fifth Avenue and Sixth Avenue. There's much else to

see.

I was told by the very nice keeper of the consoles that no one ever

asks for these Way Out episodes except one peculiar gentleman who

comes twice a year and asks to see them all.

She doesn't know his name but seems to remember the face. This is

really true.

I wonder if his name is Pell. I wonder if his face is even more

memorable than she says.

[Editor's Note: There was a bit of humor in the series, provided by

Dahl's on-camera introductions, in the first of which he said, “The

story we are about to see is

not for children, nor young lovers, nor people with queasy stomachs. It

is for wicked old women.”