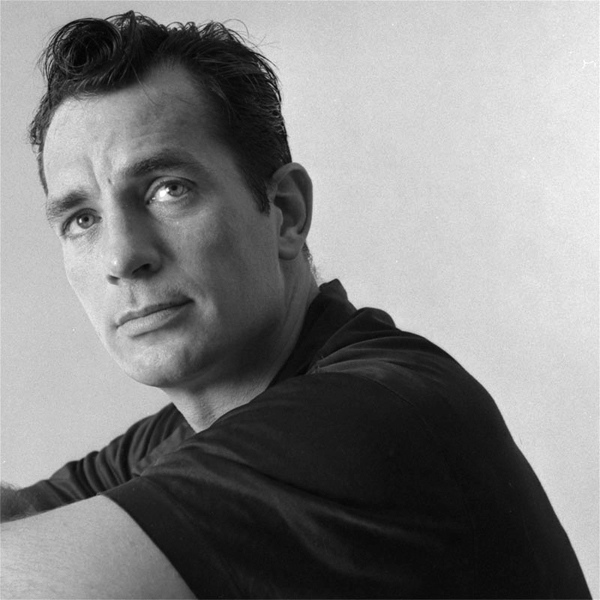

There are 1000 guys in Lowell who know more about heaven than I do.

— Jack Kerouac

Jack Kerouac left an amazing portrait of America in the second half of the 20th century — paying attention to the everyday warp and woof of things and their mythic role in the unconscious epic of the nation. To find anything comparable in the art of our time you have to look to the photographs of Walker Evans and William Eggleston, especially Eggleston.

Kerouac celebrated and eviscerated American places in long, impressionistic passages in his writing and in brief epithets tossed off in passing. These epithets, taken together, have something of the quality of the Catalog Of the Ships in The Iliad.

Paul Zahl, a regular contributor here, discusses Kerouac's geographical epithets, about America and other places, with some choice examples:

A JACK KEROUAC GEOGRAPHICAL GLOSSARY

by Paul Zahl

Kerouac had a wonderful way with vivid adjectival phrases.

In his letters especially, and wherever he could write free of

stricture or zealous editor, he would use jammed-together phrases to

describe the places he visited, the people he met, and the phenomena he

observed.

I have made a little study of Kerouac's descriptive phrases for the

cities and towns, and even foreign countries, in which he spent time.

For example he described Morocco as the place where one could see “the

true glory of religion once and for all; in these humble, often

mean-to-animals people”.

If you have spent time in a Middle-Eastern country, this phrase

instantly connects. How many people I know who have left their

inherited religion in the West and are impressed by exactly the phenomenon

Kerouac observes, right down to the flogging of the camels.

Here is a little 'Beat' geographical glossary, from the man who saw,

and wrote what he saw.

Oh, and some of them may offend you if you actually live in the place

he is describing. When Kerouac refers to “rainytown Pittsburgh”, he

captures the essence of that particular city. But Pittsburghers don't

see it this way at all!

So hold on to your hats. And get ready to smile, and maybe wince a

little.

(All these phrases come from the letters of Jack Kerouac composed

between 1957 and 1969, which are collected in the 1999 Viking Press publication edited by Ann Charters.)

Rock n Roll Hooligan England

sick old Buddhaless Europe

California TOO MANY COPS AND TOO MANY LAWS and general killjoy culture

Total Police Control America

Doom Mexico

(Kerouac survived an earthquake in Mexico City, and was

also fascinated by the interest in death which he saw in the culture

there.)

“Orlando Florida”

(Kerouac complained that you could not buy On the

Road at any newsstand in Orlando, where he and his mother lived for two

fairly long periods, so that city for him would always be in quotes.)

nightmare New Orleans

thank God for Spain! All living creatures are Don Quixote

San Francisco, that town of poetry and hate

unholy Frisco

Muckland Central Florida in Febiary (sic)

midtown New York sillies world

this New York world of telephones and appointments

peaceful Florida, winter Florida, Florida peace

Massachusetts boy-dreams of Harvard

the South where everybody is DEAD

And thinking globally . . .

so goes the Dostoyevskyan world

And from Visions of Gerard . . .

That hat, with its strange Dostoyevskyan slant, belongs to the West,

this side of this hairball, earth

the world, the uncooperative and unmannerly divisionists, the bloody

Godless forever

Home again . . .

overcommunicating America

You could probably write an essay on every pungent phrase that Kerouac

comes up with. You may also be offended by his incautious descriptions. Furthermore, they were mostly written down under the influence of

alcohol, by the author's own admission.

Yet they are evocative and at times (to me) inspired. They are also

very funny. After just a few days in London, thirty years before the rise of the

“soccer yob”, Kerouac spoke of “Rock n Roll Hooligan England”. What prescient voice is this?

If this starter glossary re-connects you with Kerouac's

voice, the voice of a man Allen Ginsberg described as “heaven's recording angel',

and sends you back to his work, try writing down more of these phrases as they catch your eye. As your Catalog grows you'll wonder, “Where did this man receive his wisdom?” and “Did

he not grow up right here in Nazareth, and do we not know his mother

and his brothers and his sisters?”

[Editor's Note: “Overcommunicating America” — we live there now, all right. And even a man who could write, decades ago, “California TOO MANY COPS AND TOO MANY LAWS and general killjoy culture” might be surprised at the way The Wellness State has calcified into his most extreme vision of the place. Jack apparently never visited my hometown, Las Vegas, but he would have nailed it, too, I imagine, in a way that would make me wince . . . and laugh. Paul Zahl just moved away from a suburb of Washington, D. C., where Kerouac and Gregory Corso once dropped in unannounced on the poet Randall Jarrell and found him “hobnobbing in Chevy Chase”, a world center of hobnobbing. Kerouac will find you wherever you are, America — you can run but you can't hide from heaven's recording angel.]

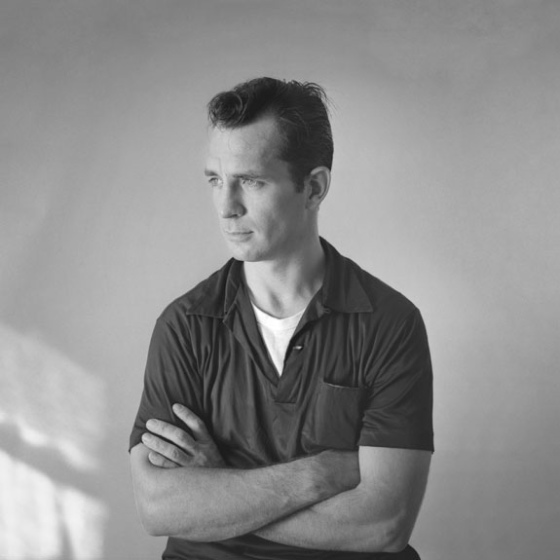

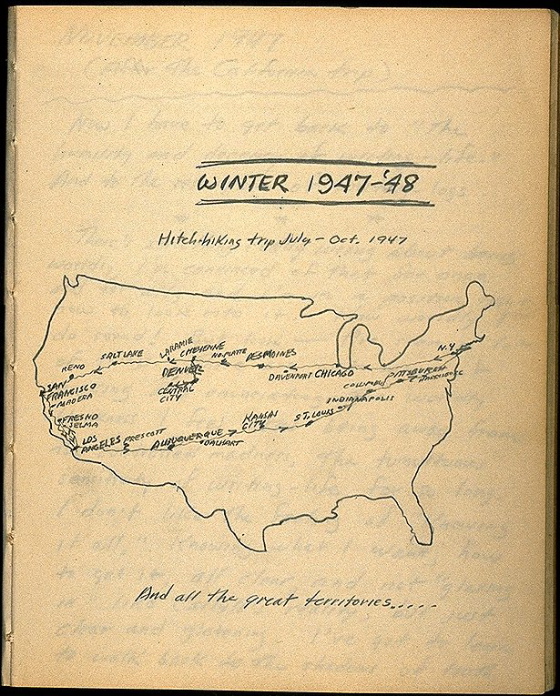

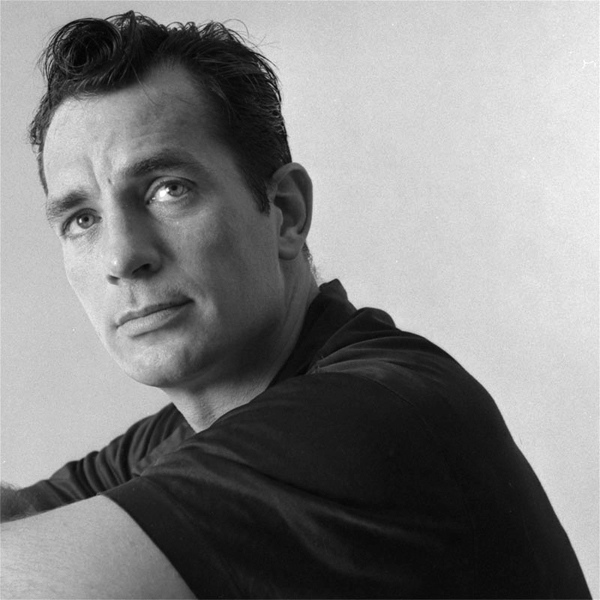

The map above is from one of Kerouac's diaries. The portraits are by Tom Palumbo. You can find more of Paul's articles in The Zahl File here.