. . . change you can believe in.

Monthly Archives: July 2009

MIRAGE

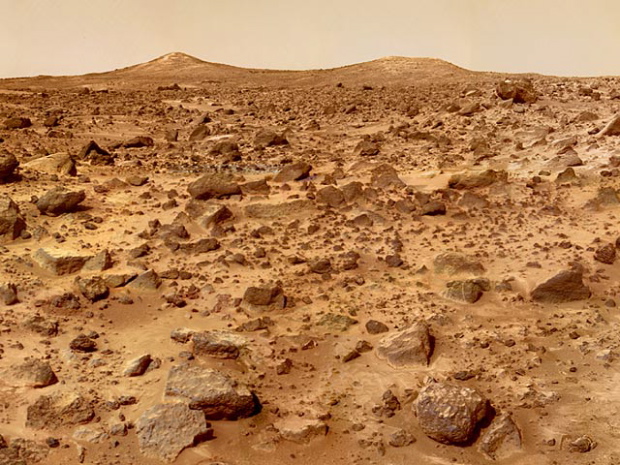

We were driving through a landscape reminiscent of ones you see in images beamed back to Earth from the Mars Rover (above) — severe, rocky, dry, empty, with no visible signs of life. It was a part of the Mojave Desert near Spring Mountain, just past the outskirts of Las Vegas, in the Lake Mead National Recreation Area.

We were myself, my sister and her two kids Harry and Nora, just arrived for their annual Dream Vacation in Las Vegas. Harry and Nora's dad, a film editor, sometimes known as the hardest working man in show business, is almost always on a job during their summer vacation, so my sister brings them here for an escape.

Rounding a bend on the twisting desert road we saw what we were looking for — a kind of mirage in the midst of the desert, Lake Las Vegas, an artificial lake at the edge of Henderson, Nevada, a Las Vegas suburb. It is surrounded by green swards, most of which are golf courses, and by what look like cookie-cutter versions of Italian villas, most of which are condos.

We parked near a little “village” at the edge of the lake, near the MonteLago Resort. This has shops and restaurants in a facsimile Italian lakeside town, next to a marina. It was violently hot and we headed more or less directly to a restaurant by the water called Bernard's Bistro. It was a genuinely charming place, somewhat upscale, and we had an exceptionally good lunch there.

This was the start of Harry and Nora's fifth summer visit to Las Vegas, and we'd wanted to see something we'd never seen before, something très Vegas, which means très weird but also weirdly amusing.

We saw it and were content.

[Photos courtesy of the Mars Rover, the Vegas Rover (Harry Rossi) and Lloydville.]

THE SEA, THE SEA

Marilyn at the beach.

What is it about that girl?

AMERICA, AMERICA

Keep your eye on the ball, baby.

[Post cover by Dick Sargent]

LA VIÈRGE AUX ANGES

This painting by Bouguereau, from 1881, is owned by the Forest Lawn Cemetery in Glendale, California, just over the hill from Hollywood. In 2005 it went up to the Getty Museum in Santa Monica on an extended loan in return for restoration, which primarily involved removing a coat of varnish that had yellowed, muting the original colors. The scan above records the restored work and comes by way of the always amazing Art Renewal Center.

I'm not sure whether or not the painting has gone back to Forest Lawn, but if you live in the Los Angeles area you're within striking distance of it, either way. If I lived in the Los Angeles area, I go see it immediately.

It's said that you either worship Bouguereau or you despise him — folks on either end of the spectrum tend to be a bit dogmatic on the subject. Anti-Modernists are inclined to place him in the Pantheon of the old masters, which seems extreme. I think Bouguereau is a great painter of the second or third rank, assuming, for example, that Jan Van Eyck is a painter of the first rank. Anti-Victorians are inclined to dismiss him out of hand as the embodiment of kitsch, which I think is even sillier.

The important thing is that his works are wonderful, in a very odd and original way. You can enjoy them immensely without worshiping them and you can recognize their limitations without despising them.

REPORT FROM NEW YORK: THE HIGH LINE

Folks who don't live in the New York City area might not know about the High Line — a stretch of elevated railroad tracks in lower Manhattan. It used to carry freight trains into Manhattan terminals but stood abandoned for years and attained a kind of mythical status, because it became overgrown with vegetation and constituted a bit of wilderness in the middle of the city. It was officially inaccessible but became familiar through photographs taken of it and the stories of people who sneaked up to have a look at it themselves.

The basic structure has remained sound and a campaign was launched to turn it into a park — a very odd park. The park opened this month and my friend Jae Song, a resident of Brooklyn, went to see it. He sends the following report of his initial impressions, illustrated with photos he took, mostly using the panorama mode on his cell-phone camera:

Went to visit the High Line.

For crowd control on opening day they set up a rule — you could only enter from one end and exit at the other. Even

though it wasn't opening day when I visited, and there was hardly anyone there, when I tried to go up the “exit” stairs there was some fascist

telling me I had to walk down to the entrance at the other end. (Why

can't people just think on their own? Why do they have to follow strict

rules without knowing what the rules are for?)

This should have tipped me off as to what I was about to experience . . .

At first — it was exciting to be able to go up to those old tracks that have been closed off for so long.

And it was really . . . nice.

A very well designed place.

There are benches that rise up from the ground in sleek fashion. There are big lounge chairs made of dark wood. There's a space with auditorium seating that looks out over 10th Avenue.

The palette is modern grey and dark brown

. . . with weeds carefully placed growing in patches here and there.

Everything is very well thought out and all . . . perfect.

I walked all the way to the far end and then went back to the middle and took a seat on one of the lounge chairs.

And as I sat there . . . I became incredibly sad.

The High Line is like one of those beautiful old historic factories that is converted into a clean modern luxury loft.

The modern sleekness has cleaned all emotion from the place. No mystery — no possibilities.

It's all too perfectly designed, too purposefully placed . . . everything —

every “haphazard” weed, every loose pebble. Even the concrete slabs on

the ground have perfectly placed irregularities. All of it makes it

impossible for me to make the space . . . my space. I can't connect with

it personally.

I can't do anything in the space that the architects and designers haven't already prepared for.

I feel controlled by whatever corporation it was that took it

over. The planners obviously wanted to keep the feel of the old High Line — but the old High Line was an iron

industrial structure that nature took over, in unpredictable ways. There's nothing unpredictable about it now.

It's like watching an M. Night Shyamalan movie. It is very well crafted — I

can't fault him for not making a very well-constructed movie — but most

of the time I don't really feel anything, and the movie has very little

life. It's not that I don't like the movie, it's that I feel I'm supposed to like it, I'm supposed to feel a certain way, but I don't, and I want to feel something but I don't . . . and that pisses me

off.

Unlike watching a Godard film. It's sloppy as hell but so exciting, and it makes me giggle, and sometimes I'm glued to the screen and I

don't even know why . . . I don't know what the hell's going on.

Why is there this need to make beautiful old things into clean

sterile piles of nothing? Do they make yuppies feel safe? Because they

don't have to think — they go, they know what they are suppose to do,

they do it, they post pics online, they check it off on their

experience list.

Why can't something just be, age and become whatever it is it is

becoming? What's with face lifts and boob jobs? What's with “luxury”

condos? What's with the High Line! Another place for people to make

money now I suppose. (There are bars and restaurants opening up all

over the neighborhoods near the High Line, and up on the High Line, too.) Personally I like a really nicely aged

steak rather than a fresh cut.

It is so sad to me . . . yet another thing in New York that has come to ruin . . .

Jae has made subsequent visits to the High Line and modified his opinion of it somewhat. New Yorkers are appropriating it and making it their own. That's what New Yorkers always do. When Central Park opened in 1873 one of its designers, Frederick Law Olmstead, wanted visitors to use it exactly as he imagined it being used — strolling its paths in a civilized manner, serenely admiring his vision of nature. He didn't want bars or bandstands or ball fields — anything that might attract or appeal to the baser natures of the great unwashed.

That didn't last long.

So there's hope for the High Line, too. Perhaps Jae will write a follow-up report on the progress of its re-incorporation . . . as a people's park.

[All photos © 2009 Jae Song]