Part One — The Case For the Prosecution

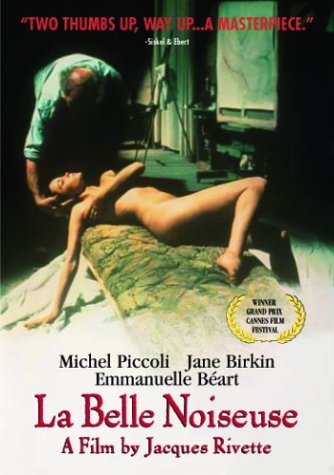

Jacques Rivette's La Belle Noiseuse is a fascinating film and, if you'll pardon the chauvinism, very French.

The psychological insights it serves up are almost unbelievably trite, which makes the grave and serious tone in which they are delivered almost laughable. But not quite. It is the préparation of the dish and the présentation which redeem it. It is a form of alchemy which one often encounters in the simplest French restaurants, where a salade frisée aux lardons will sometimes be put together as though the fate of civilization depends on its approach to perfection.

So in La Belle Noiseuse one appreciates the care and refinement of Rivette's filmmaking, the precision and elegance of the dialogue, even when the ingredients Rivette is working with are simple to the point of simple-mindedness.

One has to be on guard when an artist takes on the subject of how hard it is for a woman to live with an artist. Self-importance, self-regard and self-pity are almost always hidden among the twists and turns of such works, imperfectly masked by a self-laceration masquerading as humility but in fact presented as a higher form of the artist's noble commitment to honesty, which can apparently justify any human failing.

I don't think I'm misrepresenting Rivette's sensibility here. He's a guy who once ascribed the success of James Cameron's Titanic to the fact that Kate Winslett was fat, which allowed fat teenage girls to identify with her character. That same peevish misogyny, that same inability to penetrate the female psyche, are on full display in La Belle Noiseuse.

In La Belle Noiseuse an older artist whose creative springs have run dry is restored to his vocation by a younger woman, for whom he will be tempted to betray his long-suffering wife and partner, even as the younger woman is tempted to betray her love and partnership with an aspiring artist for whom the older man is a mentor and inspiration. (I should add that the betrayals involved here are not necessarily sexual in the usual sense of that word.)

I am prepared to believe that an older artist can be recalled to productivity by nubile flesh, and that there are women who find the role of muse intoxicating and irresistible at whatever cost it comes. The phenomenon doesn't tell us much about art, however. It probably plays itself out in every profession, and there are likely more artists inspired by a faithful lifetime companion than ones revivified by fresh meat.

Such a view, however, has no place in La Belle Noiseuse, where betrayal of a loved one for art must be seen as a tragic, bittersweet necessity — somehow intertwined with the truth of art itself. The twist at the end of the film's story, while humane on one level, only reinforces this mythology.

La Belle Noiseuse is, to put it very bluntly, nonsense, on a philosophical and psychological level, but it is a measure of the intricate delicacy of Rivette's treatment of this nonsense that one can still enjoy the film as a well-observed melodrama, unfolding with excruciating deliberation, and as an incisive portrait of people in the grip of delusions which the filmmaker himself gives every evidence of sharing.

In Part Two of this piece, I present The Case For the Defense, outlining the film's many miraculous pleasures.

Pingback: Swell belle | Hyfresh