A few more thoughts on Bob Dylan’s Christmas album . . .

Bob Dylan hasn’t referenced Christmas very often in his own songs, and the most notable references have been either wistful or rueful. There were, for example, the tatty, neglected Christmas decorations in “Three Angels”, looking down on the foibles of a heedless world . . . and these lovely, melancholy lines from “Floater”:

My grandfather was a duck trapper

He could do it with just dragnets and ropes

My grandmother could sew new dresses out of old cloth

I don’t know if they had any dreams or hopes

I had ’em once though, I suppose, to go along

With all the ring dancin’ Christmas carols on all of them Christmas Eves

I left all my dreams and hopes

Buried under tobacco leaves

This always reminds me of some other wistful lines about Christmas, in one of Robert Johnson’s songs:

If today was Christmas Eve

And tomorrow was Christmas Day

If today was Christmas Eve

And tomorrow was Christmas Day

Oh, babe, wouldn’t we have a time?

The idea in Johnson’s song is that it’s not Christmas Eve, and good times are not just around the corner — may never be again.

It’s a little surprising, then, to find Dylan in such a merry mood on his new Christmas album Christmas In the Heart. He really sounds as though he’s having fun on all the upbeat numbers — like a kid given the run of a toy store. On “Christmas Island” he seems to be contemplating a holiday in the tropics with unmitigated glee, and on “Must Be Santa”, you get a feeling he may have been dancing while he was putting down the vocal. His slightly curdled egg nog of a voice is laced with a jigger or two of intoxicating cheer.

On the more spiritual numbers, he conveys a different kind of joy — almost triumphal. He sings the first verse of “Adeste Fidelis” in Latin, punching out the words like a preacher on fire with the unimpeachable authority of the good news he’s delivering. (Now that Pavarotti has moved on, is there anybody left but Bob who can sing Latin like he means it?) When Bob sings, “Hark, the hee-rald angels sing!” you get a feeling he has them in view, or is perhaps himself a member emeritus of their band.

Christmas songs are encrusted with so many memories that singers rarely feel they have to do more than get them down, offer a respectful rendition. That’s why it’s such a shock to hear Dylan performing them, interpreting them, as though we might have forgotten what they mean, what their words are all about — not Christmas Eves past, lost times and unreachable dreams, but Christmas Mornings to come, peace on earth, goodwill to men.

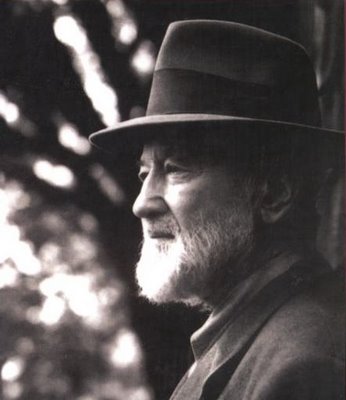

My friend Harvey Bojarsky had an interesting insight into the conceptual aspect of the album, comparing its strategy of musical collage — with echoes of American Christmas music of every kind popping up in unexpected combinations — to what Charles Ives (above) was doing in his Holiday Symphony. In that work, as Wikipedia notes, Ives wanted to write each movement as if it were based on a grown man’s memory of his childhood holidays. Ives said, “Here are melodies like icons, resonating with memory and history, with war, childhood, community, and nation.”

So it is with Christmas In the Heart. You’ve heard everything on it before, though now all the elements are mixed up together, out of sequence, out of context, the way they get mixed up in memory, and this allows you hear them anew, and see the connections between them — the secret, perhaps unconscious connections between them you’ve already made in your heart.

[Go here for some more thoughts on Christmas In the Heart.]