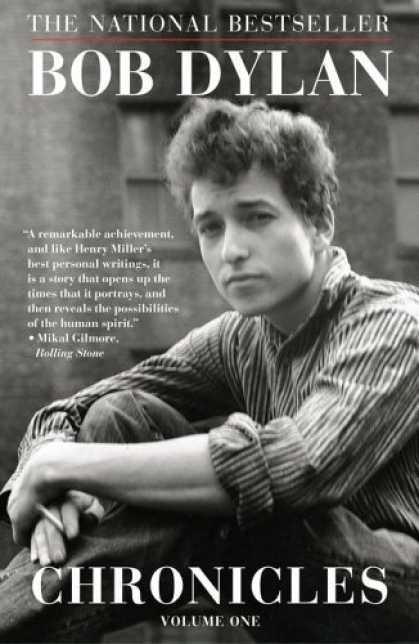

In his brilliant and eccentrically revealing memoir Chronicles: Volume One, Bob Dylan talks about a crucial inspiration in his development as a songwriter — the first time he heard “Pirate Jenny”, from Brecht and Weill's The Threepenny Opera. The lyric is written in the voice of an oppressed young girl, who recounts her fantasy of a pirate ship which will appear in the harbor of her city and bombard it in her name, destroying all her enemies and rescuing her from a life of servitude.

It is thus a surreal fiction set within the slightly less surreal fiction of the opera itself, both modes operating here within a single song. Dylan says this expanded his notion of what a song could be. He was of course already familiar with the narrative conventions of folk songs, especially the murder ballads, and he would follow these conventions in many of his own works, telling self-contained fictional or historical tales, usually with a strong social message, but “Pirate Jenny” set him off on another strategy, involving fantastical tales within tales.

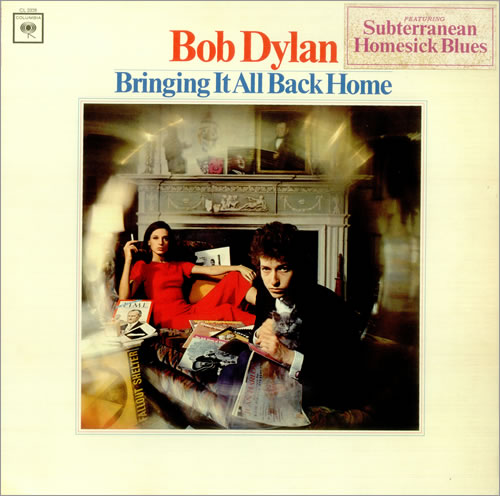

In “Bob Dylan's 115th Dream”, from Bringing It All Back Home, Dylan tells a tale in the voice of a crew member of the Mayflower, which is somehow commanded by Melville's Captain Ahab and lands in America for a series of comic anachronistic adventures. (Among the artifacts surrounding Dylan in the photograph on the cover of Bringing It All Back Home is the Lotte Lenya album on which he first heard “Pirate Jenny”.)

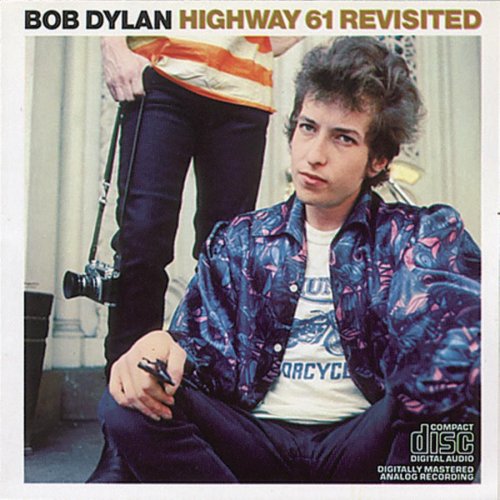

“Desolation Row”, from Highway 61 Revisited, offers a similar bit of jumbled-up, surreal narrative but has become less buffoonish, more poetic.

“Desolation Row” conjures up a vision of a very specific place inhabited by an improbable cast of characters, drawn from every aspect of culture. The real-life poets Pound and Eliot have a mythical fistfight, The Phantom Of the Opera shares the scene with Ophelia and Cassanova. It's a vision, on one level, of culture as it's actually experienced in the imagination. Lon Chaney and Charles Laughton and Victor Hugo are forever linked by The Hunchback of Notre Dame — Desolation Row is that precinct of the mind where all four of them meet up and hang out together.

On the same album, in “Just Like Tom Thumb's Blues”, Dylan presents a variation on this fractured narrative strategy, this time with a series of vignettes and anecdotes about some beat characters hanging out in Mexico. Each element of the song seems to open onto a whole narrative episode which, however, is only suggested, not recounted. It's like shards of a Kerouac novel discovered at an archaeological dig and displayed in glass cases, inviting the viewer to reconstruct the whole from them. (This is, of course, just an extension, or extreme compression, of the fragmented narrative style of Kerouac himself.)

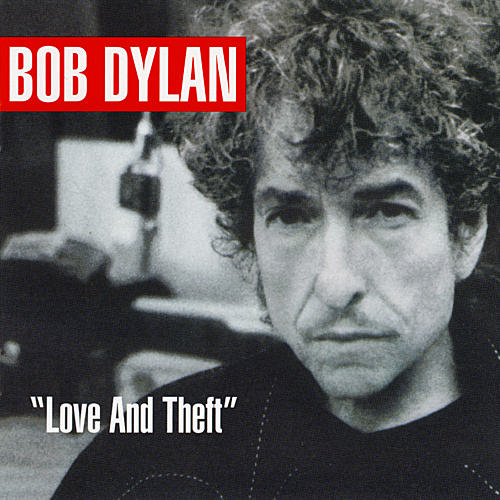

Many Dylan songs can be seen as collages of poetic images, but most are more acutely perceived as collages of story fragments, micro fictions, which suggest great narrative vistas seen fleetingly through a narrow window whose shutters open and close quickly. His song “Floater”, from Love and Theft, suggests a whole cycle of Faulknerian novels glimpsed in this way. Ironically, many lines in “Floater” were lifted almost straight from a Japanese as-told-to autobiography called Confessions Of A Yakuza, yet Dylan has used them in the context of a series of interconnected micro fictions about a place and time and characters that seem indigenously, essentially American.

Here are eight lines from “Floater”:

My grandfather was a duck trapper

He could do it with just dragnets and ropes

My grandmother could sew new dresses out of old cloth

I don't know if they had any dreams or hopes

I had 'em once though, I suppose, to go along

With all the ring dancin' Christmas carols on all of them Christmas Eves

I left all my dreams and hopes

Buried under tobacco leaves

I doubt if any of this reflects actual memories from Dylan's own life, but the lines do seem to sum up the whole life of some particular person, in a kind of generational saga told through lightning flashes of imagery.

The precise details, the dragnets and ropes, the old cloth, the ring dancing, seduce us into emblematic episodes, in somewhat the same way that the brief flashbacks in A Christmas Carol seduce us into emblematic episodes from the happier early years of Scrooge. And Dylan doesn't just leave his hopes and dreams behind, he leaves them “buried under tobacco leaves”. Here the detail is more symbolic, more open — did the narrator lose his hopes and dreams in the drudgery of work, or just in wasted hours marked out by the smoke of cigarettes?

The details and episodes evoked in these lines propel the story Dylan is telling into our own imaginations, prompting us to fill in the rest, to travel back in time like Scrooge, to visit the narrator's lost world, to construct our own sense of it, our own dream of it. And this, of course, is what all good stories do. What's left out of them is what eventually belongs most securely to us, almost as if they were our own experiences, because we have collaborated in the making of them.

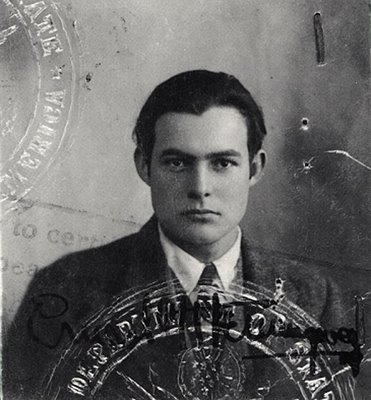

This was one of the secrets of storytelling that Hemingway knew well, and consciously, almost from the very beginning of his career as a writer. All of his best work uses this “strategic opacity”, as Stephen Greenblatt has called it, referring to Shakespeare's method of storytelling — this uncharted space that the hearer of the tale must fill in for herself.

Dylan is a great singer, a fine tunesmith and poet, but not least among his gifts is the gift of storytelling, in a fragmented, micro-fictional form of his own devising.