When my car got a flat on a country road in Vermont one chilly night back in 1997 my heart sank. I'd lent my jack to my brother-in-law three weeks before and had forgotten to get it back. I hadn't worried about it too much, because I had a new set of tires on the car, but I'd apparently picked up a nail on the road somewhere and now I was facing the consequences.

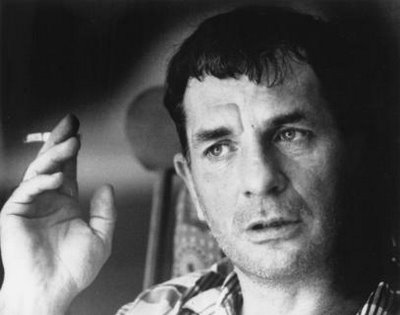

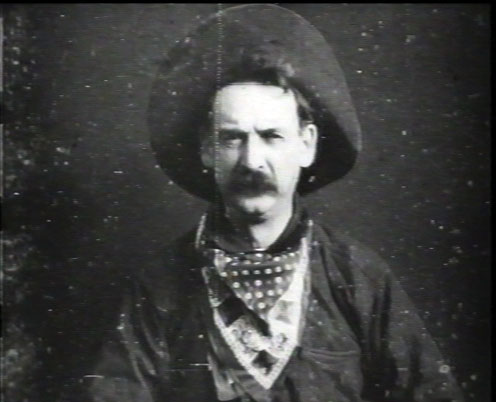

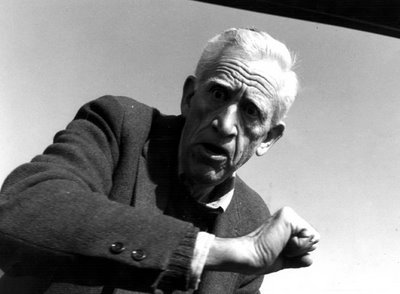

I saw the lights of a house through the trees and really had no choice but to walk up to it and ask to use a phone. An older man with gray hair, a long face and large ears opened the door, looking at me suspiciously. I described my predicament and asked if I could use his phone to call a local garage.

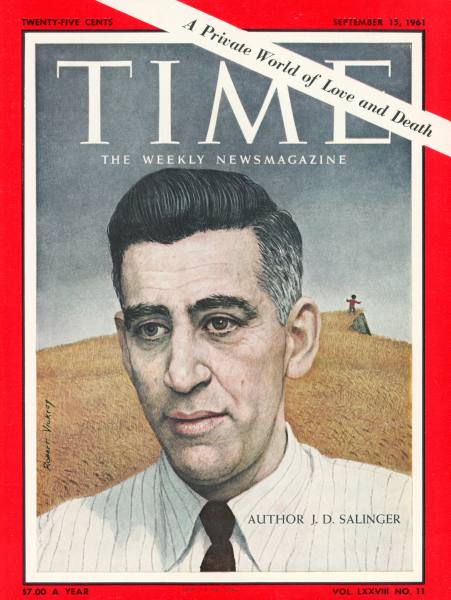

“What do you want from me?” he said. I figured he was hard of hearing and started my explanation over in a louder voice, but he waved me silent. “I'm not signing your copy of Catcher In the Rye,” he said, almost vehemently.

“I don't have a copy of Catcher In the Rye,” I said. “I had a copy in high school but I couldn't get through it so I gave it to my sister.”

“What's your angle?” he said.

I started to explain about my flat tire again but again he waved me silent. “You didn't like the book?” he asked. “Not much,” I said. “Why?” he asked. “Well, I like David Copperfield a lot, for one thing,” I explained. “I don't think it's crap.”

“I'm not answering any questions!” he shouted at me.

“Not even 'Can I use your phone?'?” I said. I realized I was dealing with a total hairpin, but he didn't look violent and it was awfully cold outside.

He showed me to the phone, gave me the number of a guy with a tow truck in Cornish, the nearest town, and hovered over me while I made the call. I asked him if I could wait inside until the tow truck arrived. “Yes,” he said, “but no photographs!”

“I don't have a camera,” I assured him, which should have been obvious. He fixed his gaze on me intently. “So . . .” he said finally, “you're more into the later books.” “What later books?” I asked.

He seemed totally bewildered. “You can't write about this night until after I'm dead!” he said. “If you do, you will hear from my lawyers!”

“You've got yourself a deal,” I said — and it's a deal I stuck to faithfully.