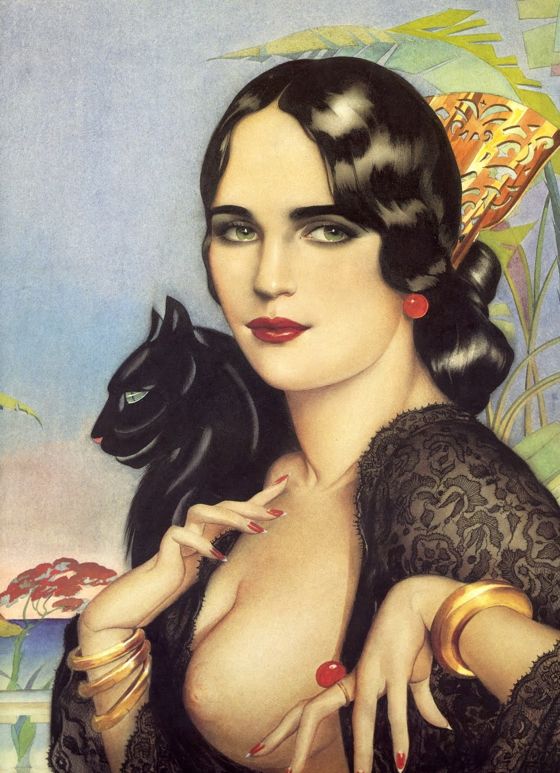

Spanish Gypsy, from 1928.

[Muchas gracias a Golden Age Comic Book Stories por la imagen.]

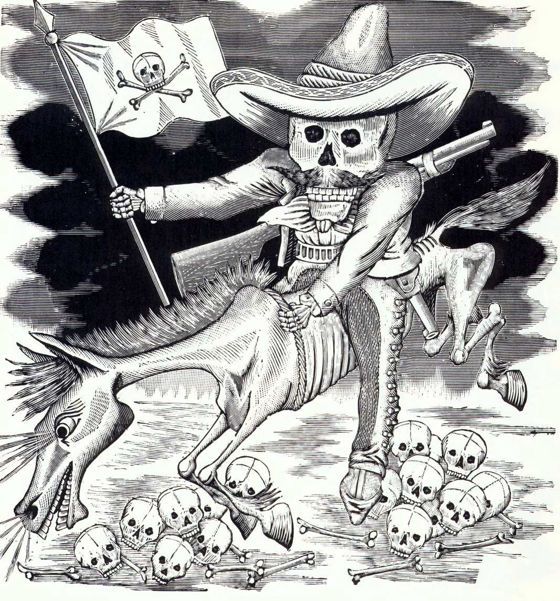

Zapatista calavera, by José Guadalupe Posada, early 20th Century.

The girls of Little River they're sweet and they're pretty

The Sabine and the Saber have many a beauty

The banks of Nacogdoches have girls by the score

But down by the Brazos I'll wander no more

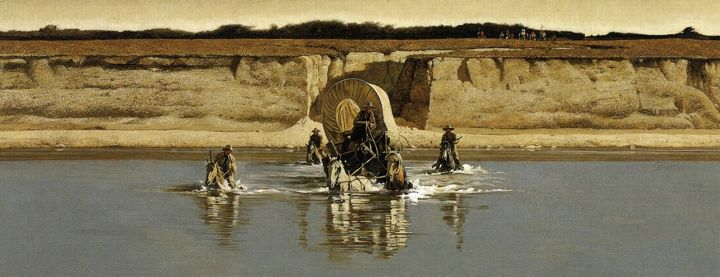

Another wonderful Western painting by Robert McGinnis. Horses and wagons crossing rivers are seminal images in movie Westerns — for Ford and Boetticher they had a spiritual quality. They would create little poems out of them, little arias, stopping the narrative to show the process in detail.

Here's Don Edwards singing the cowboy song quoted above — a Homeric catalogue of Western river names, laced with rue over a lost love:

Down By the Brazos

[Right grateful to Golden Age Comic Book Stories for the image.]

. . . a boy ever had.

On a drive up the Pacific Coast Highway with my friend Deane Evans, in a time before disco . . .

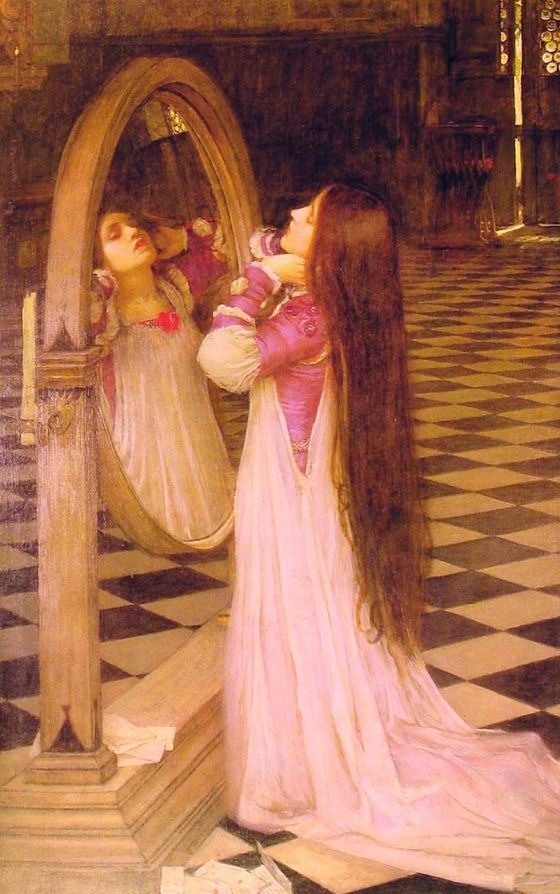

Percy Bysshe Shelley howls at the moon:

Art thou pale for weariness

Of climbing heaven and gazing on the earth,

Wandering companionless

Among the stars that have a different birth,

And ever changing, like a joyless eye

That finds no object worth its constancy?

[Image by John William Waterhouse.]

Come, my friends,

‘Tis not too late to seek a newer world.

Push off, and sitting well in order smite

The sounding furrows; for my purpose holds

To sail beyond the sunset, and the baths

Of all the western stars, until I die.

— Tennyson

Red River Valley

The composition is a bit static, though I guess you could also call it monumental, iconic. Pretty cool, all the same.

Here's something you don't run across every day . . .

[Image by Edmund Blair Leighton from the gallant Golden Age Comic Book Stories.]

Ventura and Oxnard, the city it bleeds into towards the southeast, are

by volume mostly agricultural. Along the 101 Freeway that bisects them

is a succession of malls and outlet centers, and using only this artery

one could supply all the needs of life without ever thinking of these

cities as anything other than highway sprawl. You could miss entirely

the old downtown of Ventura, that runs along Main Street for a few

blocks near the restored mission, or the tiny beach community where I

live, “on the lanes”, as the older residents say — the little lanes

like mine that run off Pierpont Avenue and dead-end at the sea.

But if you take the surface roads that lead from my lane to the backs

of the shopping centers and malls, you drive through a landscape of

cultivated fields, some of which run down almost to the state beaches,

and grow strawberries and mushrooms and many other green things which I

do not recognize.

Downtown and the lanes, like these open fields, seem frozen in a

time-warp, images of the California coast towns long ago. It can't

last. Already one sees industrial parks and condo developments sitting

preposterously isolated on the edges of the farmland. In our lifetimes,

probably, the fields will give way entirely to such things, as they

have over the course of the last century in Los Angeles and in the San

Fernando Valley.

One navigates this dreamscape with a sense of loss already. One wants

to photograph it all, just to prove it really exists — to be able to

prove it once existed. The bright hand-painted signs at the fruit stands

near where Telephone Road becomes a dirt lane, minutes from the great

outlet malls of Oxnard, brood in melancholy gaiety.

They will not be preserved, like the Olivas Adobe, which sits surreally

on the edge of the Olivas Park Golf Course, testifying unconvincingly

to the age of the Spanish land grants. The tiny beach shacks on

Weymouth Lane where I live, where lower middle-class families could

once live within spitting distance of the Golden Coast, will not

survive another generation.

Ventura is a strange place, culturally arid, hard to love for any

obvious reasons — but the quiet doom that invests all of it makes it

very sweet . . . charms the spirit.

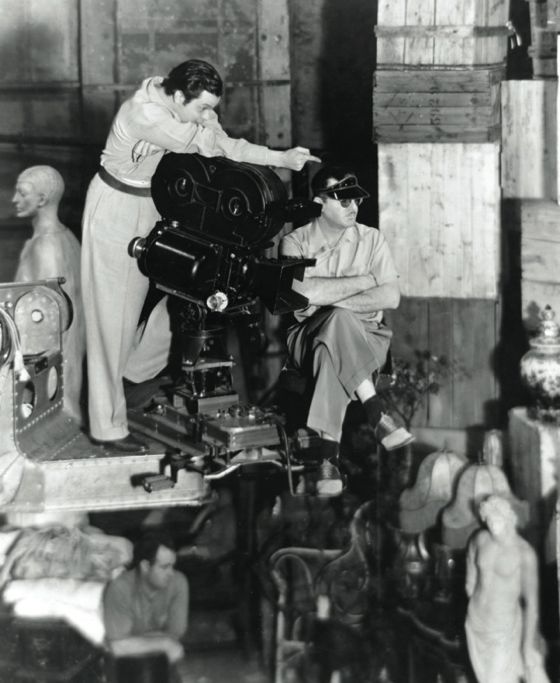

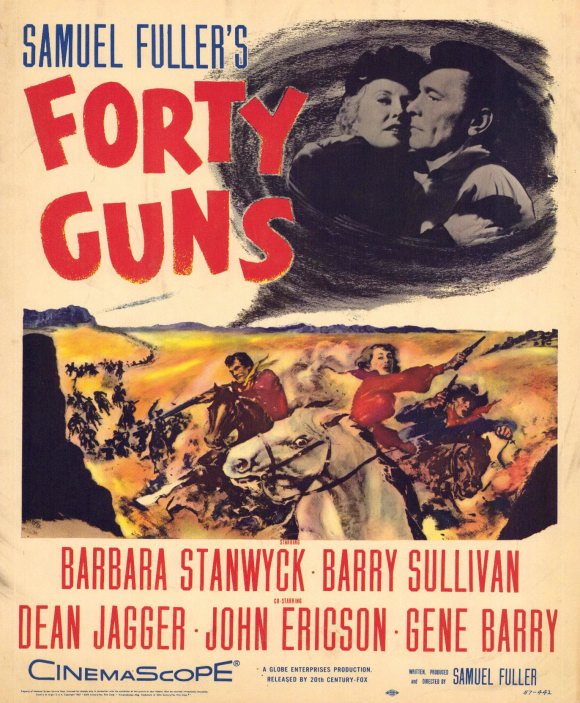

If you haven't seen it, there's no way I can convey to you how strange this 1957 Samuel Fuller Western is. I can tell you it's about a mythically powerful woman who rides the territory of her ranch with forty hired guns, like an escort of armed valets. She is a primal variant of the femme fatale, wreaking havoc on a world of collapsed males. Her type is not unknown in films of the Fifties, especially in film noir, but here she takes on the dimensions of a Greek goddess, terrible and timeless.

Her power is contested, and ultimately overcome, by a man willing to stand up to her, reducing her to a state of pliant femininity — which rarely happens in film noir — but at the same time she's such a vivid embodiment of the nightmare of the collapsed male that the triumph of the hero here feels provisional. She might have been vanquished in last night's dream, but she'll be back in tomorrow night's dream — you can count on it. The threat she poses is eternal. (Fuller had a darker fate in mind for his fatal femme but the studio vetoed the idea.)

What I can't convey is the American-Gothic vision of the Old West Fuller has concocted — it's as though Poe has lit out for the territory and found the same sickly-sweet decay in the Western myth that he found in the European myths back east.

Fuller deconstructs the classic beauty of the best-looking Western films, of Ford and Wyler and Hawks, by pushing their methods into realms of extreme self-consciousness. His camera travels endlessly on tracks, swoops deliriously on cranes, exaggerating the conventions into a new form, one with no restraints on style.

This is a Rococo Western, in which style breaks loose from narrative goals and serves only archetype.

It's a very odd and very beautiful film, and not like any other I know. By the time directors like Godard began to embrace Fuller's daring methods of self-conscious filmmaking, they were ready to abandon genre itself, except as an ironic referent. (It's worth noting, however, that Godard quoted a shot from Forty Guns in Breathless — it was clearly on his mind as he began to forge his own style.)

Fuller stays inside the Western genre in Forty Guns but lays waste to it mercilessly from within. Only a man who loved the form could have done this, just as only a man who loved women could have feared them as much as Fuller fears the commander of the forty guns, the high ridin' woman with the whip.