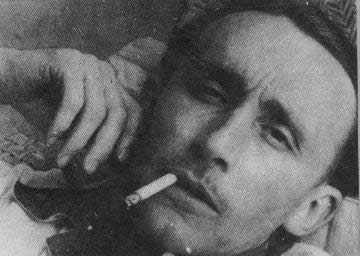

André Bazin (above) wrote some of the most penetrating analyses of how screen images work, but, as I’ve suggested before, he had a blind spot in his obsession with a movie’s connection to visual fact, its function in providing “evidence”. He was saying something important about the psychological effect of the camera’s intimate relationship to physical reality, but his theories can’t explain why the imaginary spaces created in animation, for example, can have the same emotional and psychological power, the same cinematic power, as spaces recorded photographically.

This blind spot also led Bazin to draw a misleading contrast between stage space and screen space. With stage space, he argued, we’re always half aware of the backstage machinery that creates theatrical illusion, while a screen image gives the illusion that it’s only a window onto a wider, complete world.

This is not always true, even — perhaps especially — in the work of one of Bazin’s heroes, Orson Welles. I recently ran across a passage from the critic Chris Fujiwara which sums the issue up nicely:

In radio, all space is “off” and is evoked by sound, which alone has

materiality. From his experience in radio, Welles sometimes brings to

film a purely vocal offscreen space, as in the scene of the dying Major

Amberson contemplating something that “must be in the sun.” But

offscreen space as conjured by the looks and movements of characters to

impose an imaginary spatial coherence – this is something Welles has

little interest in. He prefers to leave offscreen space unfilled, to

reorganize the world with each cut, or to deny the offscreen by

enfolding all space, all revelation within a single shot. Welles’s

cinema is a forgetting of offscreen space, a denial of its potency.

This strikes me as quite true. The amazing long take in The Magnificent Ambersons of George eating strawberry shortcake in the kitchen as he talks to Fanny and then to Uncle Jack behind him in a deep onscreen space, seems to me to represent a precise and wholly self-contained theatrical environment. Even though the shot records a convincingly “real” place, I still feel that Uncle Jack enters the scene in the far background from “the wings”.

Welles has thoroughly theatricalized that space — we have no appreciable sense at all of a wider, complete world beyond it.

[The Fujiwara quote comes from a special issue of La Furia Umana, an online cinema magazine, devoted to Welles — which I found via Wellesnet. The issue contains articles on Welles in English and in other languages.]