From 1920, when Westerns were Westerns and movie posters were works of art.

[From (where else?) the wondrous Golden Age Comic Book Stories.]

From 1920, when Westerns were Westerns and movie posters were works of art.

[From (where else?) the wondrous Golden Age Comic Book Stories.]

I love the way she sits a horse — looking to sign on as her forty-first gun.

In the 1880s. Note the rider in the center holding a dog in his lap.

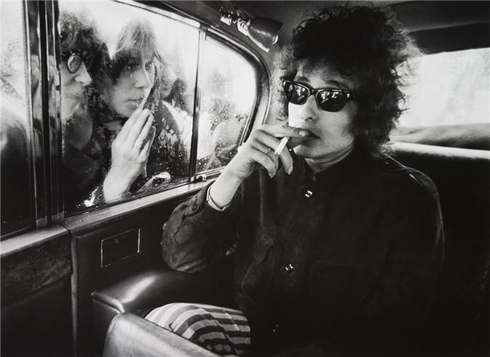

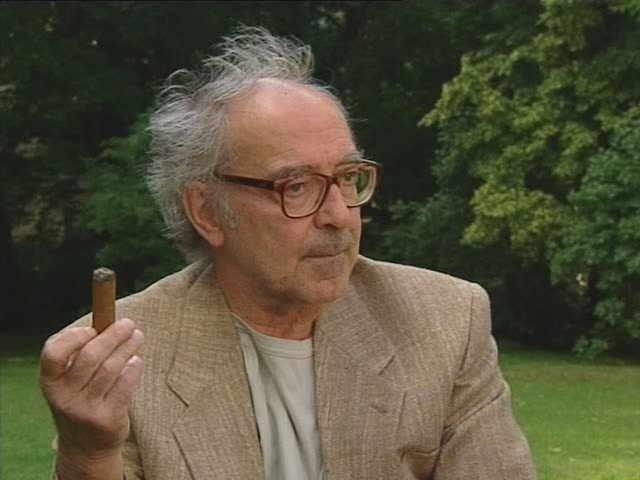

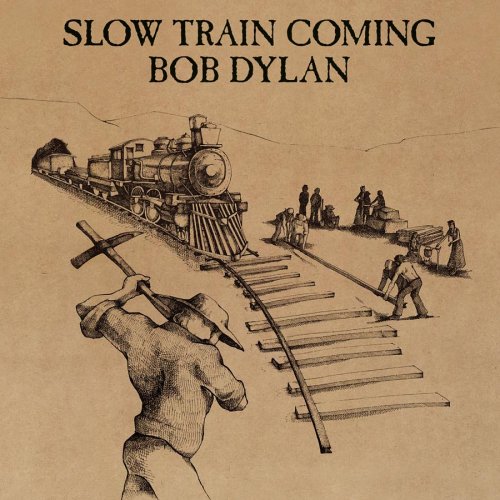

Jean-Luc Godard always had a strong identification with Bob Dylan, a sense that their careers, their artistic journeys and even their lives were somehow linked, even though they never worked together. The idea is not as strange as it sounds. Both were artists steeped in tradition, the tradition of cinema in Godard's case and the tradition of American music in Dylan's. Both were looking for ways to bring what they loved from those traditions into the present, to give them a form that would be alive for the future. Both were re-mixers, who made startling recombinations of old things that they then inflected with a purely contemporary resonance.

Both also had serious motorcycle accidents that resulted in periods of seclusion.

In the late 70s, each artist began to lose touch with his traditional audience — Dylan wasn't making much of a showing on the charts anymore, Godard was finding it harder and harder to get financing for his films. They weren't cutting the same figures on the cultural stage that they had in previous years.

Godard took an interest in Dylan's fortunes, kept track of his successes and failures — since they seemed in some ways to mirror his own. It wasn't just a question of sympathy with a fellow artist in a similar predicament — it was a question of an almost mystical identification with one of the only artists of the 20th Century operating at his level of genius and accomplishment, and thus one of the only artists of their time who could possibly understand what it felt like to be Jean-Luc Godard in commercial and cultural isolation.

Most surprisingly, Godard has reported that when Dylan “turned to Christ” in 1978, he said to himself, “That will happen to me, too.” Then he forgot about it, until he made Hail Mary in 1984. “Look,” he said. “Dylan warned me.”

[Photo by Jae Song]

Another micro movie essay on cinema, from the usual suspects, Kendra and the three J's — Champs

Contre Champs, French for shot-countershot, one of Jean-Luc Godard's

bêtes noires. Find out why!

Micro Movie Essay #4 — Champs Contre Champs:

YouTube

Facebook Fan Page

Prescription for the future of cinema — go back to the beginning and rethink everything.

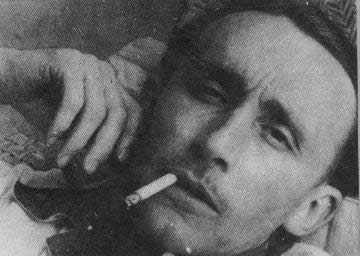

André Bazin (above) wrote some of the most penetrating analyses of how screen images work, but, as I’ve suggested before, he had a blind spot in his obsession with a movie’s connection to visual fact, its function in providing “evidence”. He was saying something important about the psychological effect of the camera’s intimate relationship to physical reality, but his theories can’t explain why the imaginary spaces created in animation, for example, can have the same emotional and psychological power, the same cinematic power, as spaces recorded photographically.

This blind spot also led Bazin to draw a misleading contrast between stage space and screen space. With stage space, he argued, we’re always half aware of the backstage machinery that creates theatrical illusion, while a screen image gives the illusion that it’s only a window onto a wider, complete world.

This is not always true, even — perhaps especially — in the work of one of Bazin’s heroes, Orson Welles. I recently ran across a passage from the critic Chris Fujiwara which sums the issue up nicely:

In radio, all space is “off” and is evoked by sound, which alone has

materiality. From his experience in radio, Welles sometimes brings to

film a purely vocal offscreen space, as in the scene of the dying Major

Amberson contemplating something that “must be in the sun.” But

offscreen space as conjured by the looks and movements of characters to

impose an imaginary spatial coherence – this is something Welles has

little interest in. He prefers to leave offscreen space unfilled, to

reorganize the world with each cut, or to deny the offscreen by

enfolding all space, all revelation within a single shot. Welles’s

cinema is a forgetting of offscreen space, a denial of its potency.

This strikes me as quite true. The amazing long take in The Magnificent Ambersons of George eating strawberry shortcake in the kitchen as he talks to Fanny and then to Uncle Jack behind him in a deep onscreen space, seems to me to represent a precise and wholly self-contained theatrical environment. Even though the shot records a convincingly “real” place, I still feel that Uncle Jack enters the scene in the far background from “the wings”.

Welles has thoroughly theatricalized that space — we have no appreciable sense at all of a wider, complete world beyond it.

[The Fujiwara quote comes from a special issue of La Furia Umana, an online cinema magazine, devoted to Welles — which I found via Wellesnet. The issue contains articles on Welles in English and in other languages.]

Kendra, James, Joe and Jae return in a new essay on cinema — Tracking!

— which critics are already calling the greatest micro movie ever

made. Personally, I don't see how it can ever be surpassed. Craig

Schober records sound and helps move the platform! David Ure assists!

The screen explodes with excitement!

Micro Movie Essay #3 — Tracking:

YouTube

Facebook Fan Page

Prescription for the future of cinema — go back to the beginning and rethink everything.

. . . the Jesus of the Gospels was transformed into some sort of cavalry or Boy Scout troop leader, complete with guidon. He's ready for business, church business, getting the organization in line.

This fresco by Piero della Francesca is a great work of art — Aldous Huxley once called it “the best picture in the world” — but I defy anyone to be moved by it, except on an aesthetic level. Easter is happening somewhere else . . . or so I've heard tell.

This is Arnold Böcklin's Mary Magdalene Weeping Over the Dead Christ. Almost everything about it strikes me as wrong — psychologically, dramatically, narratively, even theologically. The translucent black mantle lends the image a perverse erotic quality. The Magdalene's grief seems melodramatic, almost self-involved — the beautiful figure of the dead Christ becomes a prop for a diva.

And yet . . . it delivers a grisly, Gothic frisson, of the sort Böcklin specialized in, unsettling, macabre. It's hard to stop looking at it.

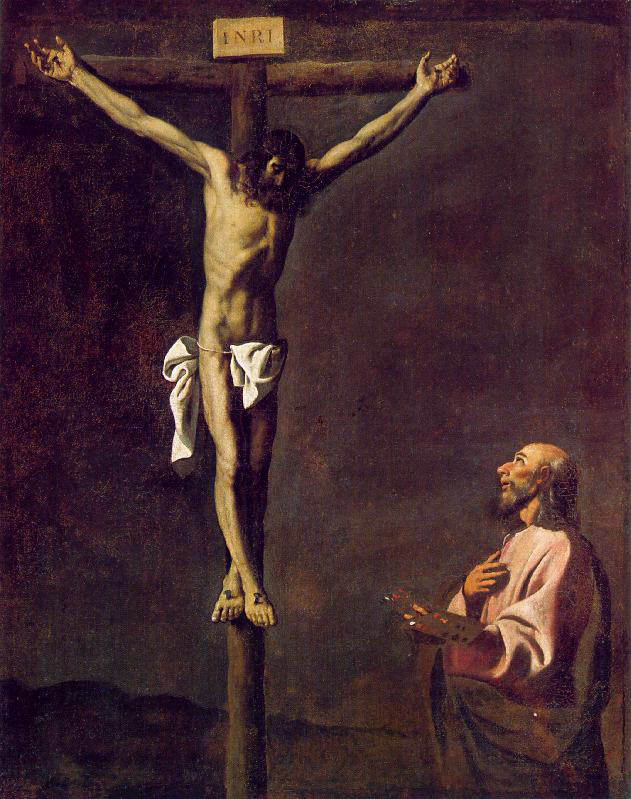

For Francisco de Zurbaran, Spanish artist of the 17th Century, painting Jesus on the cross was in some sense the same as standing before Jesus on the cross. The figure with the palette is said to be Saint Luke depicted as a painter, but surely Zurbaran was painting himself into the crucifixion scene — seeing his witness with oil paints as the virtual equivalent of eyewitness testimony.

I don't know if they do that kind of thing anymore.

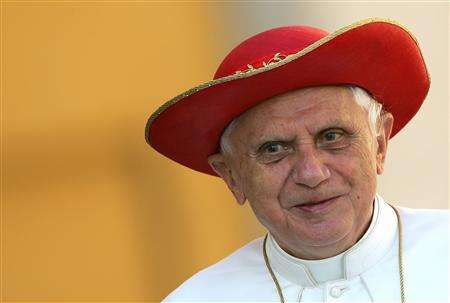

Like Blackwater and other large corporations beset by image problems, the Catholic Church is quietly exploring the possibility of a name change. Pope Benedict XVI has appointed an advisory committee composed of respected cardinals and prominent lay persons to study the issue.

Vatican spokeman Father Federico Lombardi admitted the existence of the committee yesterday, but said the Pope was far from a decision on the subject. “It's just something that needs to be considered,” Fr. Lombardi said. “I mean, let's face it, when most people hear the name 'Catholic Church' today, what they think is, 'Holy Roman Fuck Buddies', and that cannot be good for the church's mission on earth, which is to provide satisfying but innocent companionship for adult males in holy orders who want to spend quality time with young, attractive boys.”

Names under consideration by the committee include “The Pastoral Party-Time League” and “The Jesus Playhouse Group”, though insiders say that the Pope himself is leaning towards “Big Peter's Boys Club International”, because, as the Pope is reported to have said, “It makes me feel all wiggly inside.”