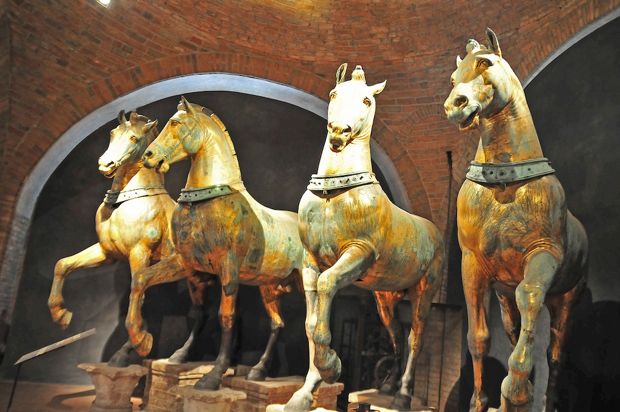

To me, these are the greatest works of art ever created. I had a nearly overwhelming emotional response to them when I first saw them, adorning the facade of the basilica in St. Mark's Square, Venice. They are, of course, magnificent images of horses, and I love horses very much, but they also have an odd spiritual quality. To me they seemed on that first viewing like an image of the grace of God as a team of work horses — patient, kind, tireless, gallant, indomitable.

No one knows when or where they were made. Many dates and points of origin have been proposed — going as far back as Greece at the time of the building of the Parthenon. They don't look like horses of that era of art to me. The horses of the great Parthenon frieze have an otherness to them, an aura of the purely equine — they are magnificently themselves.

The Horses of San Marco have been imbued with the sculptor's emotional relationship to horses, a sense of what they represent in addition to what they are.

The best scholarly guess about them today is that they were made in the second or third century A. D., somewhere in the vicinity of Constantinople. This feels right to me — they seem like works of the Christian era. They were certainly standing somewhere in Constantinople when the Venetians plundered it in 1215 and took the horses back to their lagoon.

Napoleon swiped them in turn when he conquered Italy and took them to Paris, but they were returned to Venice in 1815, after Napoleon's demise, and set back up on the facade of the basilica, which is where I saw them in the early 80s. Soon after that they were moved to a display room inside the basilica, because they were being severely damaged by air pollution, and replicas took their place on the facade.

Originally the four horses pulled a chariot in some sort of triumphal monument, possibly at the great hippodrome of Constantinople. I suspect they feel more at home in a church, though the relatively small room in which they're currently kept does not show them off to best advantage.

Jan Morris, the great writer on Venice, had this to say about them:

They are works of art of such mingled grace and compassion, such magic

in fact, that down the centuries millions of people have taken them to

their hearts. It is not just that they are beautiful. They really do

seem transcendental.

. . . to my mind the way the animals incline their heads so tenderly one

towards another, the thoughtful look in their eyes and the soft

clouding of their breaths on winter mornings — all these things make it

apparent to me that they were never actually made by anybody, but

simply came into being as darlings of God.

Amen.