Souls For Sale is, I think, the second best movie ever made about Hollywood, and makes a perfect pendant to the best, Sunset Boulevard. Souls For Sale is a portrait of Hollywood as a kind of Eden, just as Sunset Boulevard is a portrait of Hollywood as a kind of purgatory.

The sheer, delirious joy of movie-making before the studio bean-counters took full control of the industry is present in Souls For Sale. The film tries to present a balanced view of Hollywood from the other side of the camera, but it can't really — it's too swept up in the nuttiness and energy and attractiveness of the movie folk.

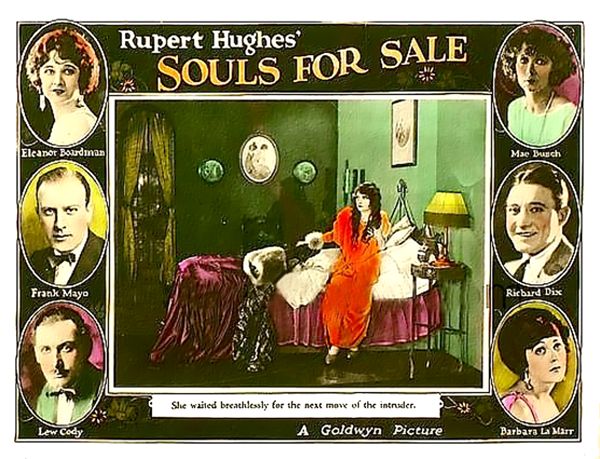

The film features a lot of cameo appearances by real Hollywood stars and directors of the time. One of them is especially poignant. We get a glimpse of Erich Von Stroheim at work on a set for Greed. We know now that he was creating one of the greatest works in the history of American art, but the cameo was filmed when the production still belonged to Sam Goldwyn's company. Before Greed was completed, that company was sold to Metro and the production thus came under the control of Louis B. Mayer and Irving Thalberg, who, in an act of unspeakable thuggishness, decided to mutilate Von Stroheim's masterpiece, to send a message to the rest of Hollywood's talent — you are no longer in control here . . . the industry you built now belongs to thugs like us.

In Souls For Sale you can see what was lost in that transfer of power — the giddy excitement of a new art form still in the hands of the artists who created it — just as in Sunset Boulevard you can see the rot and decay of that erstwhile Eden under the influence of the thugs. It's no accident that Louis B. Mayer was outraged by Sunset Boulevard. It was an epitaph for everything he personally destroyed.

The giddiness of that time before the thugs took control informs every moment of Souls For Sale. It's a thoroughly self-reflexive work of art, which pretends to examine how the dream world of the movies is constructed while itself infected with the very dreams it pretends to examine. This tension in its point of view is quite deliberate and often played for laughs, though it more often results in a kind of surreal poetry.

The story opens on a train racing through the desert on its way to Los Angeles. A young bride on her wedding night has suddenly become revulsed by the man she's married and jumps off the train at a remote watering station. She wanders hopelessly through the desert until she comes upon . . . an Arab sheik on a camel, who rescues her from death. He's an actor on location with a film crew, making a movie.

So we have moved with the mad logic of a dream from melodrama to costume drama to comedy. The whole film navigates a similar dream landscape — it's a hall of mirrors from which we never emerge. At the climax, an intertitle informs us that a real hurricane is threatening to wreck the artificial storm set up for the climax of the film within the film — and we proceed to watch the “real” artificial storm ruin the “fake” artificial storm.

If Jorge Luis Borges had ever made a movie, I suspect it would bear an uncanny resemblance to Souls For Sale.

The film was based on a novel by Rupert Hughes and also directed by Hughes (who was Howard Hughes's uncle.) He was a successful playwright, novelist and historian who directed seven films between 1922 and 1924 — then went back to writing. Souls For Sale is a handsomely mounted and photographed production, with fine performances, and it has a few images of real grace and power. Hughes was either exceptionally well-supported by Goldwyn's studio technicians or else he had a genuine gift for directing. In either case, it would be interesting to know why he abandoned the craft.

He left us a minor masterpiece, though — a vision of what the movies might have been without “boy geniuses” like Irving Thalberg and “benevolent patriarchs” like Louis B. Mayer.

Here's some more on Rupert Hughes, from an April entry in my classic Hollywood blog, “Carole & Co.”:

http://community.livejournal.com/carole_and_co/293673.html

I saw “Souls For Sale” on TCM not long ago. It's a fascinating look at the industry in the early 1920s, made at a time Hollywood was fighting back against the public perception that it was morally bankrupt following the Arbuckle and Taylor scandals.

Thanks so much for that link — very interesting!

Glad you like it. You and your readers are always welcome at “Carole & Co.”; we've been up for more than three years, with at least one entry nearly every day (today's was #1250). Check us out at http://community.livejournal.com/carole_and_co

Pingback: Silent Hollywood looks at itself | Game of Consequences