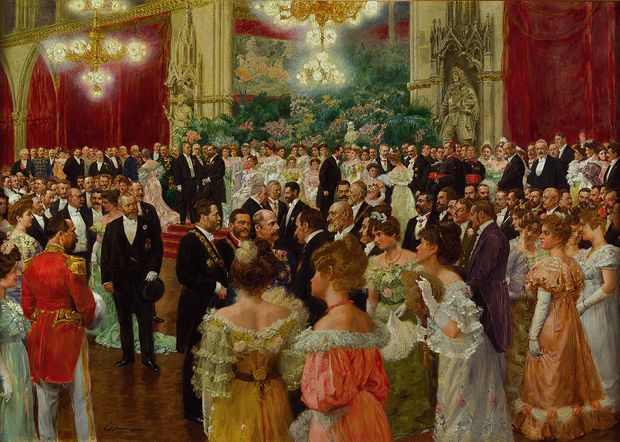

The Golden Age of Vienna, the decades just before the Great War, remains a potent image for the modern world. Everything was splendid in the Austrian capital then, and everything was rotten. Everyone seemed to know that it was all about to come crashing down in horror. This produced two responses from artists and thinkers — a deep penetration into the pathology of the modern world, and a sort of prospective nostalgia for the sweetness of what was gay in the present . . . a presentiment of what the world would be like when it was gone.

The pathology of Vienna in that era remains — this sneaking suspicion that our culture is rotten at its heart, that all its supposed splendors are trash. The gaiety is gone — replaced with a manic consumption of things and experiences, each act of which devalues the currency further. Beauty, sex, love don't even look real anymore, even from a distance, however skillfully the lighting is arranged.

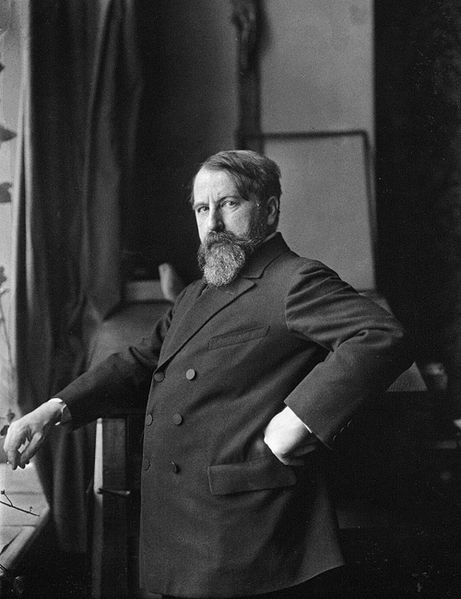

The Viennese playwright and novelist Arthur Schnitzler (above) combined a bit of both reactions in his art, though it was mostly diagnostic. Schnitzler was a doctor, and had a cold side, partly professional and partly perhaps the result of wanting to insulate himself from emotional infection by his patients. In respect to his work, we are the patients, receiving the worst news a doctor can give, and though he gives it with great elegance, he gives it straight — he doesn't mince words.

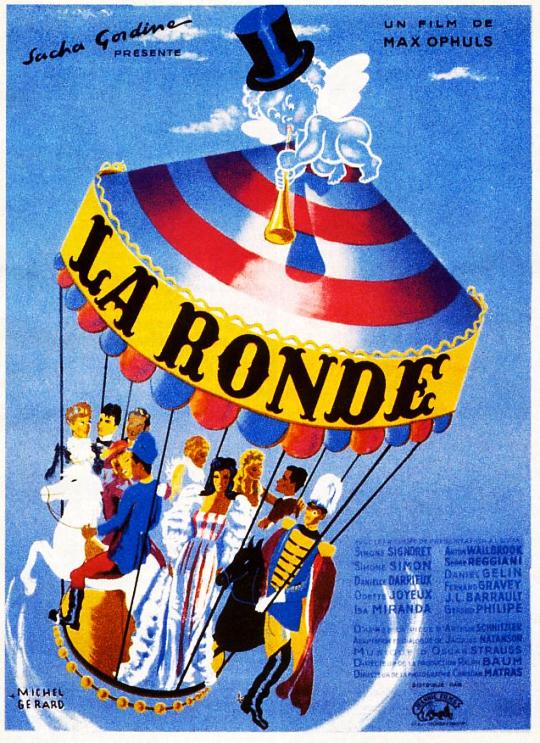

Movies have been based on Schnitzler's work since the silent era. Max Ophuls filmed two of his plays. The last film Stanley Kubrick made, Eyes Wide Shut (above), was based on a Schnitzler novel. Of course, all of these adaptations, except perhaps for Kubrick's, have been either Bowdlerized or softened in some way. Schnitzler is hard to take straight.

Ophuls's 1950 film La Ronde, based on Schnitzler's play Reigen, is softened only a little. We still have the merry-go-round of sexual encounters, all basically sad, all tending to demolish both romantic dreams and the various social pieties about love and marriage. But in the extraordinary final episode of Ophuls's film, the director allows us to believe that in the most degraded acts of sexual intercourse there is a tiny trace of human exchange that is redemptive — or might be redemptive, if the participants could credit it.

The feckless count in that sequence, struggling to remember a drunken night of love, is bewildered by what he feels for the whore he wakes up with. The whore, with her sweet acceptance of his confusion, offers a kind of benediction. There's a grace present in their exchange which doesn't quite seem to point the way to anything — but it's something, a little something, and it's very moving.

I'm not sure that that little something is still with us, in the utterly degraded culture of the present day — but perhaps a trace of it remains, like the lingering scent of flowers from a corsage lost in a ballroom where brilliant waltzes were danced.

Brilliant prose, painful insight, wonderful revelations. Thank you

Thank you, John!

S.T.D.’s can be classy.

It’s a gift that keeps on giving.

“the utterly degraded culture of the present day”: the lament of every older person since the beginning of time!

But sometimes they’re right.