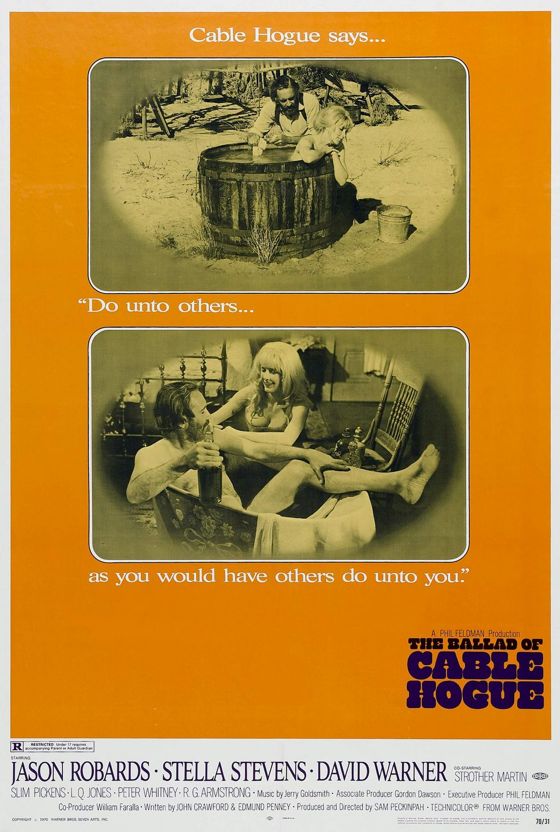

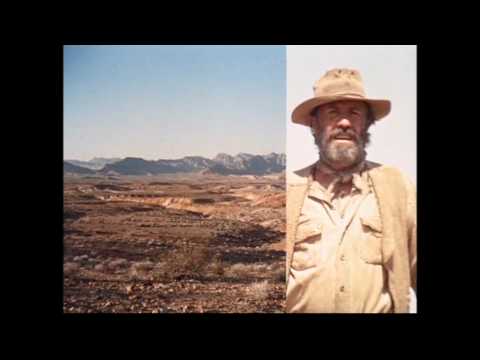

Just a few months after he delivered The Wild Bunch, in 1969, Sam Peckinpah started work on its unlikely follow-up, The Ballad Of Cable Hogue. Hogue is so sweet and sentimental that one is tempted to read it as an attempt to atone for the brutishness and meanness of the preceding film.

It’s a film that defies category. Part revenge saga, part love story, part romantic comedy, part sex farce, part elegy, it’s a work that delights mostly in telling stories, in the slow rhythms of a good yarn spun out before a fire on a chilly night. Audiences of the time were baffled by it and uninterested in a sweet and sentimental film from the director of the The Wild Bunch. The studio that made it seemed equally baffled and uninterested and did not promote it aggressively. It was a colossal flop at the box office in 1970, but its reputation has grown steadily over the years, and rightly so. It’s a really wonderful film.

Like Ride the High Country and The Wild Bunch it’s a twilight Western, a film about the passing of the Old West, but it’s neither tragic nor savage on the subject — more bemused and fatalistic. It has none of the nihilism and bitterness of The Wild Bunch, and one is further tempted to ascribe this to the fact that Peckinpah didn’t write the script, but that would be unfair — his commitment to the material is absolute. In his later years he called it his favorite film, and it was the one work he wanted young people to see when he lectured on college campuses.

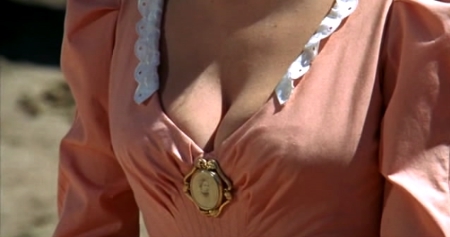

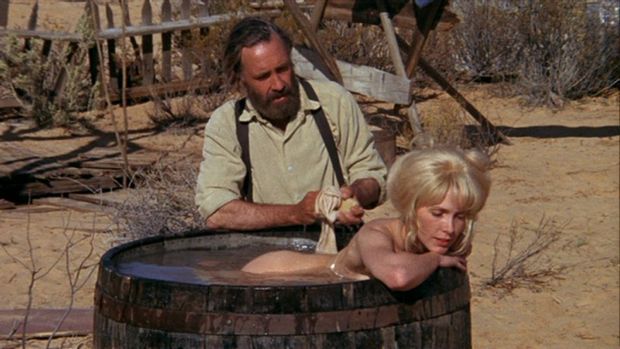

The love story is the heart of it, and it’s one of the best and most powerful love stories ever told in a Western — all the more so for the fact that it starts out so conventionally, even crudely. Cable Hogue, visiting a nearby town to file a claim on some desert land where he has improbably found water, catches sight of Hildy, a cheerful whore with a heart of gold. She’s lovely and magnificently sexual, and Peckinpah concentrates his camera on her cleavage — pointedly, almost obsessively.

Hildy is presented as a sex object, something to leer at, and Peckinpah leers at her with gusto. But that changes. It changes because of the way Cable, played with charm and intelligence by Jason Robards, treats Hildy — with respect for her humanity — and because of the way Stella Stevens, in an equally fine performance, expresses that humanity in Hildy. By the end of the film, one is not ogling her boobs — one is studying her eyes to see what she’s thinking, what she’s feeling. These things have become matters of paramount importance.

It’s an amazing bait and switch, turning this sex object into a complicated woman we care about, and it’s almost unprecedented in the Hollywood Western. It becomes unbearably moving. The climax of the relationship, and in some way the climax of the film, occurs during a scene in which Hildy visits Cable’s cabin on his claim. She slips into a nightgown in the cabin and then opens the door for Cable, who’s waiting outside.

Cable looks at her, half-silhouetted in the lamplight behind her, and says, “That’s a sight for sore eyes.” “You seen it before,” she reminds him, but he shakes his head and replies, “Nobody’s seen you before, lady.” To her, it means being seen as someone reborn, with her shady past gone, irrelevant. To lovers of the Western genre, it means looking at a woman as a full person, not just a reward for male heroism or an occasion for male gallantry.

It’s a tentative venture into territory the genre might have explored more fully if cynical Westerns like The Wild Bunch hadn’t sounded its death knell. John Ford, for all his courtliness towards women, only created one female character in a Western as rich as Hildy — Maureen O’Hara’s Kathleen Yorke in Rio Grande.

The Ballad Of Cable Hogue is full of fabulous incidents and subplots, but in the end they all really serve to set off the story of Cable and Hildy — and the love of Cable and Hildy irradiates the rest of the narrative. It leads to an act of unexpected forgiveness between mortal enemies, and seems to be the real source of Cable’s love of the desert, and even of his country.

When Cable signs a contract with a stage line to make his spring a station on their route, assuring his fortune, one of the stage drivers presents him with an American flag, which he flies proudly over his lonely outpost. He’s lowering it one evening when Hildy shows up to stay with him for a while, whereupon he runs it up the pole again, as a kind of salute to the woman.

Hildy becomes by implication the spirit of the nation — the Eternal Feminine that leads it on. Ford’s work often suggested this idea, but rarely personified the feminine as acutely as Peckinpah and Stevens managed to do in this film. It’s a startling achievement.

The image of the flag flying over Cable Springs at twilight in a beautiful wide shot is grand and iconic, worthy of Ford. The film is filled with such images, but cluttered with stylistic tics like split screens, zooms and extreme telephoto shots. “This is a modern film, totally up to date!” they scream, in the language of 1970. In the language of today they have another message — “This is an old film!” Hogue has dated on this score to a far greater degree than other films made around the same time in a more classical style, like The Godfather.

This is the only thing that keeps Hogue out of the front ranks of the Western, but it doesn’t vitiate the radical humanism and deep emotion that drive it.

Nice one, Lloyd–especially this: “By the end of the film, one is not ogling her boobs — one is studying her eyes to see what she’s thinking, what she’s feeling.” That’s really, really true.

A neat trick by Mr. Peckinpah.