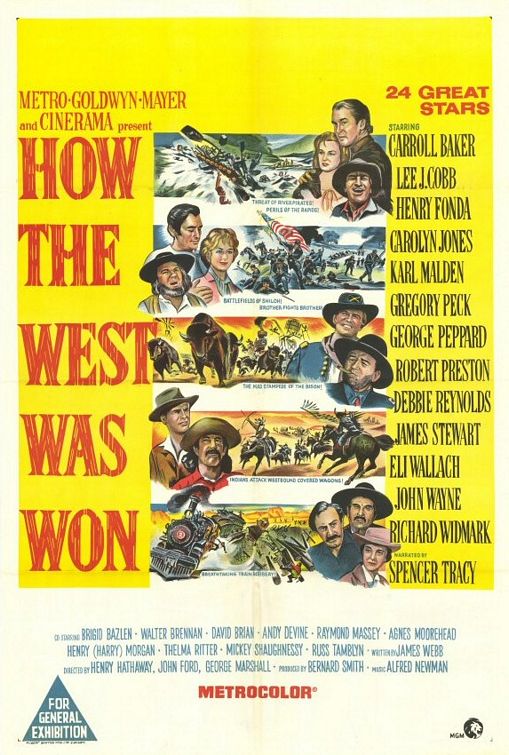

How the West Was Won is not really the frontier epic it aspires to be but a curious sort of Western-themed variety spectacle, a cavalcade of “attractions”, something like Buffalo Bill's Wild West. On its original release, the central attraction was the Cinerama process in which it was presented — a three-projector system which wrapped a super-widescreen image nearly halfway around a theater for a grandly immersive experience.

It was genuinely enthralling, as I can attest from having seen it in that process twice, once as a kid when it came out and once nearly forty years later as an adult. On both occasions I got lost in the hallucinatory beauty of the images, and didn't think too much about the intertwined narratives they served.

The vertical seams between the three strips of film which made up the Cinerama image were apparent in the original process, although one tended to ignore them after a while. Recently, though, the film has been transferred to DVD with the seams digitally removed, more or less completely, which allows one to experience the images in a new way. Of course on a TV screen they don't have the visceral impact they did in the theatrical Cinerama presentation, but one can still appreciate how beautifully they are composed, and the film's narrative content assumes a new prominence.

The film is episodic, covering a wide range of locales and time periods, but the episodes are all linked by characters established in the opening section (above) whose descendants carry on the drama through time. The script, which won an Academy Award, is very skillfully constructed in this regard, so that the sweep of the narrative never feels chaotic. It does fall apart at the end, though, in the final of the five major episodes, “The Outlaws”.

This section of the film had script problems and was revised and re-shot in parts during production. What's left is a halfhearted reprise of High Noon, culminating in a shoot-out on a moving train, which mixes stunning location work with crappy backscreens in which the principal actors do daring things in a studio.

It's an unfortunately underwhelming end to the big show.

The film has an all-star cast, with actors that are often not really suited to their roles, chosen instead for their iconic stature as stars of the Western genre. Jimmy Stewart is way too old for the role he plays as Carroll Baker's love interest, and Gregory Peck is way too staid for his role as a feckless gambler. But it doesn't matter — these stars are just being paraded before us for nostalgic purposes, the way an aging Buffalo Bill was driven around the arena at his shows in a carriage when he was no longer able to sit a horse comfortably.

Debbie Reynolds is given several song and dance numbers which are stylistically closer to scenes in a musical than to musical interludes in a Western drama — but again, it doesn't matter. This is, as I say, a variety show, not a coherent epic.

The biggest problem with the casting is that George Peppard, bland and unconvincing as a man of action, must take the baton for the final dash to the film's finish line, and he's not up to it. He is asked to carry the anti-climactic climax — something a star of real charisma might have done — but instead only contributes more mediocrity to the perfunctory conclusion.

Still, all in all, it's a most unusual and entertaining variety show, elevated often to a higher level by the stunning images of classic Western iconography — river rafts and steamboats, wagon trains, Indian attacks and a buffalo stampede, steam locomotives and galloping bandits — all brilliantly shot in the real wide-open spaces of the real American West. In those rare moments when the drama works on its own terms, the combination of spectacle and emotion is thrilling.

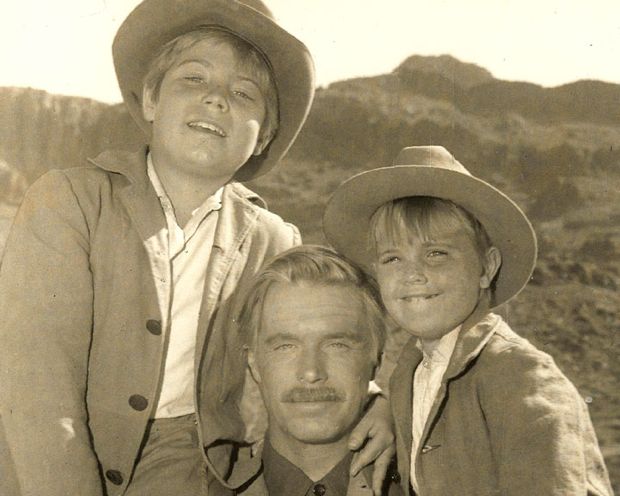

[In a follow-up post, here, Paul Zahl reflects on one of those rare moments, in the John Ford-directed section of the film, with photographs of the location where it was filmed, which Paul recently visited.]