Portrait of Jane Russell in The Outlaw, by Vargas.

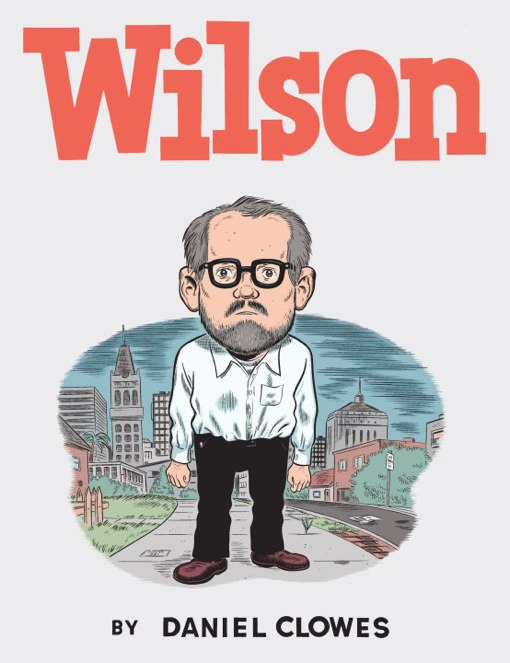

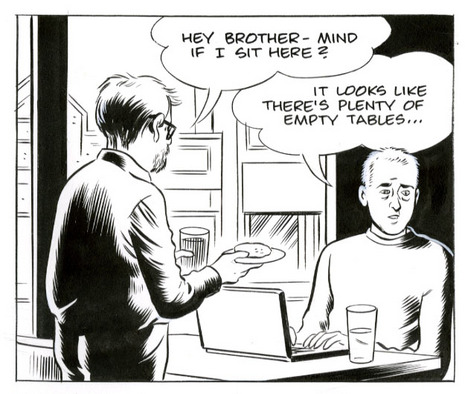

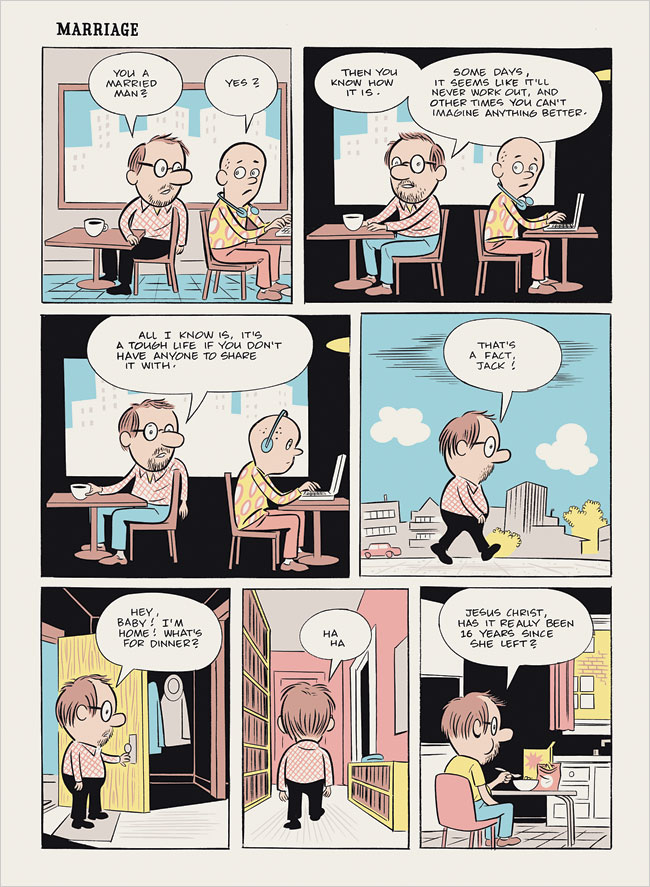

Wilson is a new graphic novel by Daniel Clowes, the author of Ghost World. Clowes is one of the great fiction artists of our time, and Wilson is his darkest work to date.

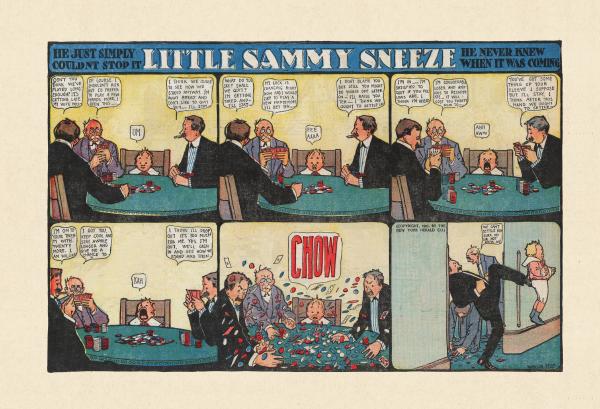

It's a sort of existentially bleak version of Winsor McCay's Little Sammy Sneeze, a strip McCay drew in the years before he created the legendary Little Nemo.

In McCay's strip, Sammy finds himself in a new place and situation every week, and as events unfold around him he starts a build-up to a sneeze, which explodes eventually with awesome power, severely disrupting or destroying everything around him. It's a strange idea for a strip, not really funny but oddly satisfying, in an anarchic way.

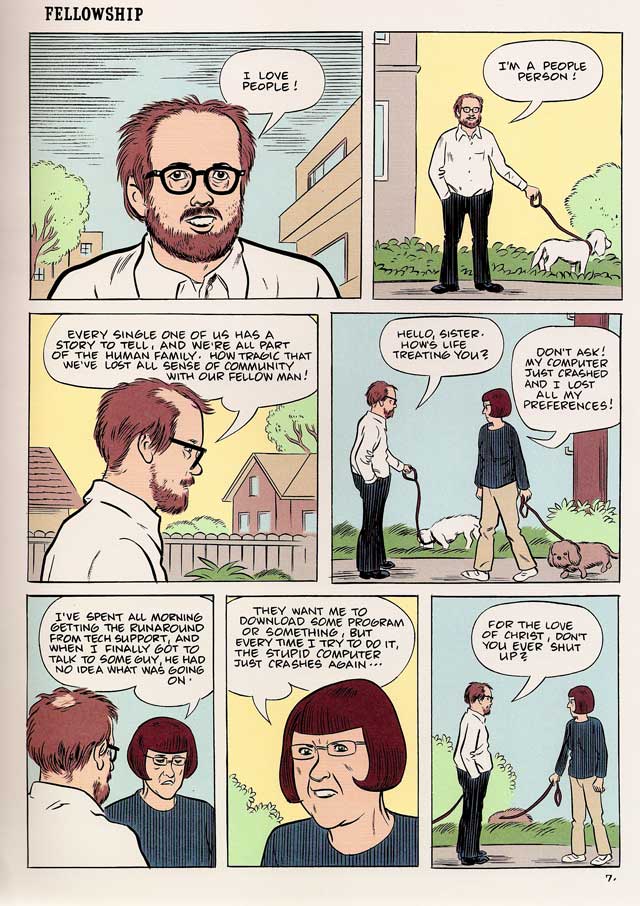

Wilson consists of self-contained one-page episodes all featuring a single protagonist, Wilson, a lost soul. Wilson has insights into life or hopeful encounters with other people all of which explode by the end of the page in an outburst of self-deception or cruel narcissism. As these emotional dead ends accumulate, Clowes constructs a portrait of genuine and utterly hopeless despair. Kierkegaard said that “the precise quality of despair is that it is unaware of itself”, and such is Wilson's.

It's not satisfying on any level, but rather heartbreaking, infuriating, sickening. It sucks us into the black hole of Wilson's psyche and makes us feel that there's no way out of it. It's slightly terrifying.

A life's narrative emerges from the self-contained episodes, a story of sorts, and they are varied by being done in contrasting styles, usually in Clowes's familiar naturalistic mode, using color panels, but sometimes in black-and-white pages and sometimes in crude comic-book caricature style. The variations only serve to emphasize the relentless coherence of Wilson's spiritual pathology.

It's a profound meditation on contemporary angst and one of the finest of all graphic novels.

Willem van de Velde, The Gust, 1680.

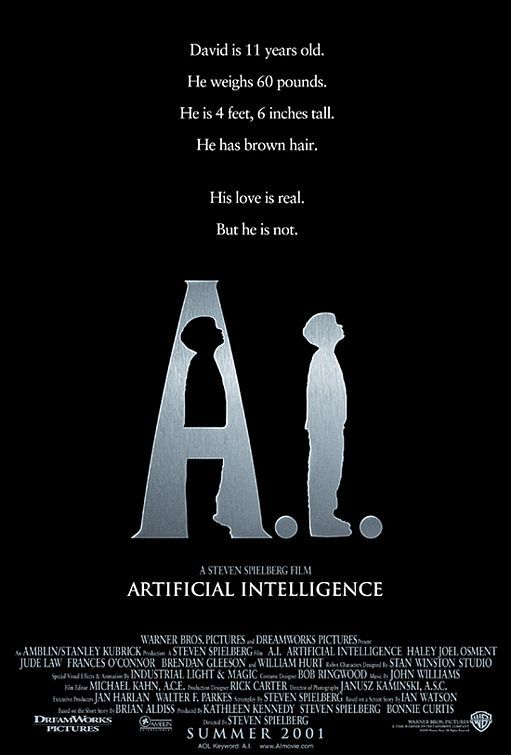

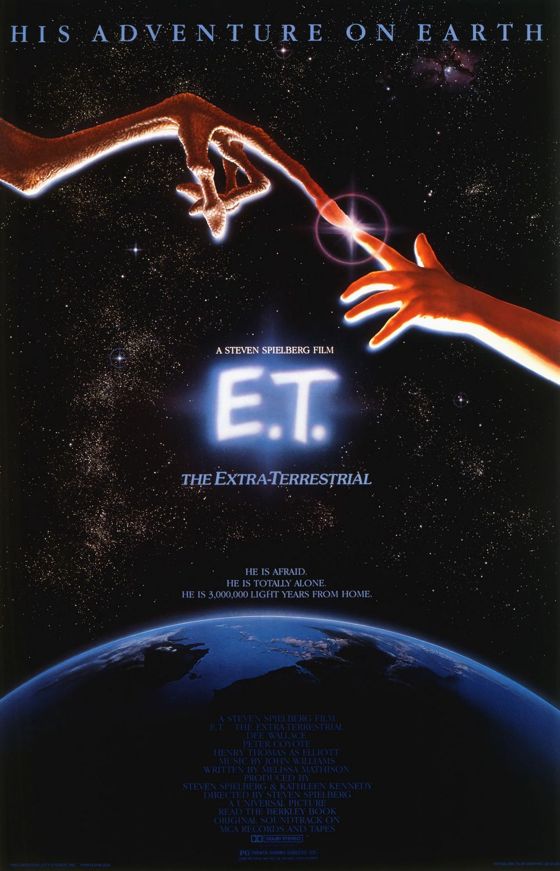

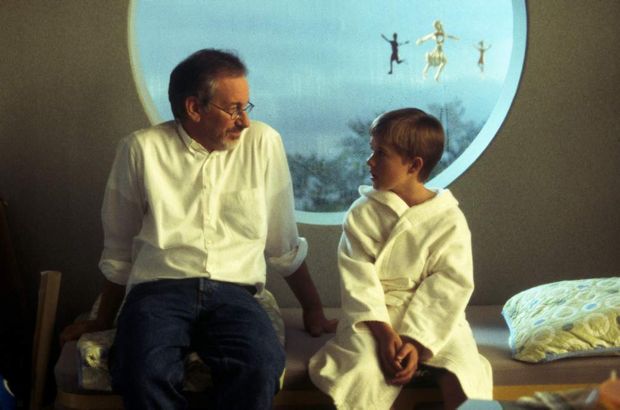

When I walked out of A. I. I truly didn’t know what to make of it. It's an extremely weird movie, and I couldn’t decide if it was weird on purpose or by mistake.

My first reaction was that it had a lot of interesting ideas that weren't really thought through or dramatized — that it was just a kind of philosophical mess, and very cold. But then I started to wonder . . . and I couldn’t stop wondering.

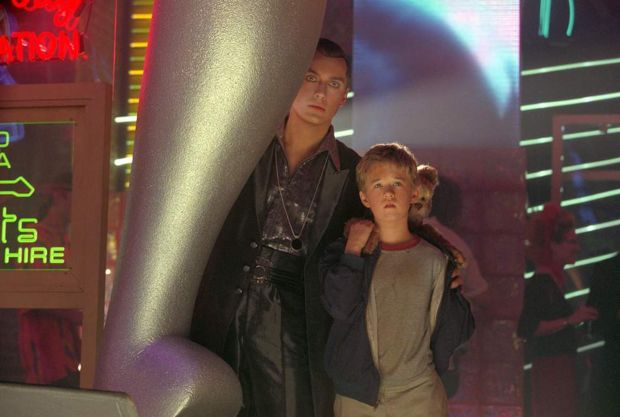

I think Kubrick must be responsible for the emotional subversiveness of the film — you root for a robot, while all the human characters seem hollow and lost. It's like a world where humans have put all their dreams into machines and are empty as a result.

David doesn't get to act like a real hero, and you can’t fully trust his passion, because it's created, “artificial” . . . and yet his quest is so pathetic, and he's so brave and hopeless, that eventually it seems very touching (partly because Osment's performance as David is so brilliant.)

I began to think that perhaps it's not a statement about machines versus humans at all, but just a fiendish Kubrick trick, a way to talk about parenthood and divorce and self-obsession — about the way some modern parents see kids as toys or consumer goods, reflections of themselves, disposable when inconvenient.

There has certainly never been a more powerful metaphor for a child's need for unconditional love from a parent — David stares into the face of the Blue Fairy for two thousand years! — and to see that need unfulfilled is very disturbing. And maybe, I thought, it's also some kind of cautionary tale about humanity surviving only as an echo, in the machines it has created. And maybe, too, the robots are symbols of the stories we tell, and these stories are our only true reality . . .

A few days after seeing the film I remembered that while watching it I associated the animatronic teddy bear with an Ewok. There are so many movie references in the film. The fake forest with the mist and the moon from E. T., the “Flesh Fair” from the Road Warrior series, the gigolo echoing Clockwork Orange, The Wizard of Oz, of course, in many places, Titanic and Close Encounters (and even 2001) at the end . . . and Pinocchio and The 400 Blows throughout.

I started thinking about the connection between A. I. and E. T., which Spielberg has always said was about divorce, his own parents' divorce, explaining that when his world busted apart he took refuge in fantasy and sci-fi, and it saved him. But in the end he had to say goodbye to it — to let E. T. go. On one level, A. I. is about how hard it it is — maybe how impossible it is — to let go of such fantasies, which linger in our psyches the way the robots haunt the humans. All the robots are like fairytale characters, simple and unchanging, and noble — even Jude Law, whose desire to please women is so sweet and heartfelt. But they aren't real, so in the world of A. I. we see what happens when we we abandon our kids to Disney, use the TV as a babysitter. We make it impossible for our kids to be “real”, which we can only do by loving them and spending time with them.

A friend of mine knows some young parents in Pennsylvania for whom having kids is just something extreme to “do”, like getting a tattoo or a body piercing, something to make life more “real” . . . but A. I. warns what happens when we want to be loved unconditionally without feeling the responsibility to love unconditionally in return . . . we create robot children, with yearnings that can never be fulfilled.

In some ways, A. I. is a horror film version of E. T..

I think it was kind of cool, in a fiendish way, to relate the teddy bear visually to an Ewok. I loved the Ewoks and I loved the teddy bear. Just one more example, I think, of telling us that the robots are our dreams and fantasies.

I was literally raised on TV. I grew up in a household where the TV was turned on in the morning and never turned off until the last person went to bed, even if no one was in the room with it. But all this is different for Spielberg because of his parents' divorce. Faced with the terror of that he turned to his fantasies for salvation, and they saved him, but only temporarily. He had to let E. T. go and learn how to make it in real life. I think maybe A. I. is a tragic vision of the impossibility of that for a child scarred by divorce or abuse, by what seems (at least at the time) to be a withdrawal of a parent's love.

This all makes more and more sense to me in terms of A. I.. We give our kids to TV and movies and video games, then we get angry at the TV and movies and video games for not raising them right, just as the orgas in A. I. are angry at the mechas — not because the mechas are less human than they are, but because they are more human . . . as the characters in fairytales are more human, more real, more present than many kids' parents today.

The question that’s so hard to answer about the film is “Why can't we like it?” — why is it so disturbing and unsettling? One possible answer is that we aren't meant to like it — that it's a tragedy . . . reminding us that the only thing that creates the wonder of childhood, or goodness in a person, is a parent's unconditional love, and if that is withdrawn, it can't be recaptured, except in a fleeting moment of fantasy. In a way, it is only David's intense, heroic need for his mother's love that “creates” the moment at the end. This is the only reward Spielberg offers him in the film — the memory of his need, that survives everything, civilization, humanity itself. It's a way of saying that long after our world is gone, the one thing that will echo through time is a child's need for love.

In that sense, the movie is meant to make us afraid of failing children, to hate ourselves for failing children — to judge everything by how we treat our children. In this day and age, that doesn't make for a fun film.

In this sense, Spielberg is criticizing his own movies, to the degree that they may seem to offer fantasy as a redemption of the world we have made. Fantasy is just a bandage for the wounds of an unhappy childhood, wounds that never heal. It would have been so easy for Spielberg to make us cheer for David, to show him doing heroic things, to restore him to his mother forever, to have her make everything all right. But he refuses to do this — and we hate him for it, hate the movie for it. But maybe that's just a way of displacing the hatred we're meant to feel for ourselves, for what our society has become on the most basic level.

The movie thus becomes a deconstruction of Spielberg's own work, a deconstruction of corporate cinema, for selling us this bandage as a cure. And this is bound to make us angry, because we love Spielberg, we love corporate cinema. But think what it meant for Spielberg himself to execute this deconstruction — because he probably loves Spielberg movies even more than we do. E. T. was what Spielberg, the child in Spielberg, created to take the place of his absent father. Perhaps only finding a substitute father in Kubrick allowed Spielberg to really let E. T. go — to upend it, to subvert our memories of it.

If Kubrick and Spielberg were doing this on purpose, then perhaps A. I. does become one of the greatest movies made in our time — an analysis of the narcotic cinema that distracts us from real things. If they did it by accident, then it still might be one of the most important films made in our time. It opens a way to the future of movies, not by showing us the future of movies but simply by blasting an opening through the movies of today.

A friend of mine said the audience he was in laughed when the teddy bear climbed up on the bed at the end. It was ridiculous and pathetic, totally anticlimactic. But maybe we are laughing at ourselves, maybe Spielberg is laughing at himself, maybe Kubrick was laughing at Spielberg. We thought the Ewoks would save us.

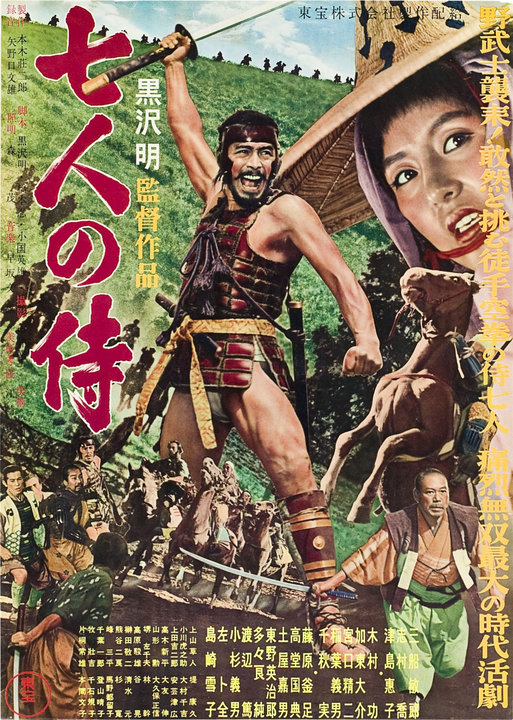

Watching Akira Kurosawa's masterpiece for the fifth or sixth time, in the wonderful DVD edition from Criterion, I finally realized what it's all about — not war, not courage, not sacrifice, but character. It's a movie about how to live.

The down-at-heels samurai who get recruited to defend a village of farmers, for some rice and for the hell of it, have trained themselves meticulously for a profession which is no longer in demand. Their dream of attaining wealth and status through fighting has vanished. Isolated and impoverished, their kind is often hunted down, robbed and killed by the peasants they used to dominate. These samurai take on a job which their leader tells them “could be the one that kills us”. They are truly past hope, even of surviving. But that's not the end of it — only the beginning. I'm reminded of a moment in a Terence Rattigan play, pointed out to me by my friend Paul Zahl, in which a character is asked, “What is there beyond hope?” He answers, “Life.” So it is in Seven Samurai.

In facing and accepting a life without hope, the seven warriors are able to live it to the fullest. They find out, at last, who they really are, and they have a chance to prove who they really are to others, to us.

The farmers they set out to save turn out to be hardly worth saving — this is not a tale about defending the good, the innocent, the worthy but weak. The samurai come to have affection for the farmers in spite of their imperfections, with the full knowledge that the farmers would betray them at a moment's notice if it served their interests.

It is altruism for its own sake, just as fighting the bandits is warfare for its own sake. The odds are never calculated too finely. If they were, everybody in this film would just go out and hang themselves, as one hysterical farmer suggests doing at the beginning of the film, when warding off the bandits seems impossible.

Most importantly, this is not a movie about redemption, of the sort that almost every Hollywood film for the past twenty years has promoted. It is not the story of some losers who, by hard work and gumption, achieve the goals they have set for themselves, redeem their lot in life. Nothing is changed by the epic battle fought here — it has not made the life of farmers better as a general rule, nor has it fulfilled the thwarted dreams of the samurai. Something changes, or is revealed — a terrible beauty is born, in Yeats's phrase — but it's all interior, some might say spiritual.

There is nothing programmatic about the existential gesture of the samurai — each one faces hopelessness in an individual way, one with philosophical calm, one with steady resignation, one with cold competence, one with good cheer, one with irony, one with idealism, one with self-hatred. Each response offers its own strength to the collective, and it is the collective acceptance of and respect for difference which make this aggregation of strength possible.

It is a warrior's code, on one level — there is no fudging things in mortal combat, good intentions don't matter, illusions can be fatal. One faces the world as it is, one plays the hand one is dealt. But the code of these hopeless samurai, a warrior's code divested of self-interest and expectation, transcends the profession of arms. It seems to suggest a way of living for all men and women — the only way of really living, really being alive, in a brutal, ugly world.

Once, in a time of despair about his life and career, and perhaps about his faith as well, Bob Dylan says that these words popped into his mind — “Here I will stand, whether God will deliver me or not.” He says that his despair immediately vanished.

To make a stand without hope is where life begins, and eternity as well. In this film the seven samurai, the ones who live and the ones who die, become immortal.

My friend Paul Zahl reminds me that as teenagers we used to visit this painting often at the National Gallery Of Art in Washington, D. C. We loved it then and I still love it.