Henry Hathaway’s film True Grit, from 1969, is a wonderful entertainment, respectful of, if not exactly faithful to, the great Charles Portis novel on which it’s based.

The powerful emotional impact of the novel is achieved by indirection, by characters who don’t speak about what’s really going inside them because they’re rarely aware of it. We read their inner lives though their actions, which are often surprising, startling, even shocking. Hollywood is generally afraid of tales told this way, afraid that audiences won’t get the point, so the adaptation of True Grit brings the emotions and motivations of the characters to the surface. Paradoxically, this leaves the viewer with less to respond to.

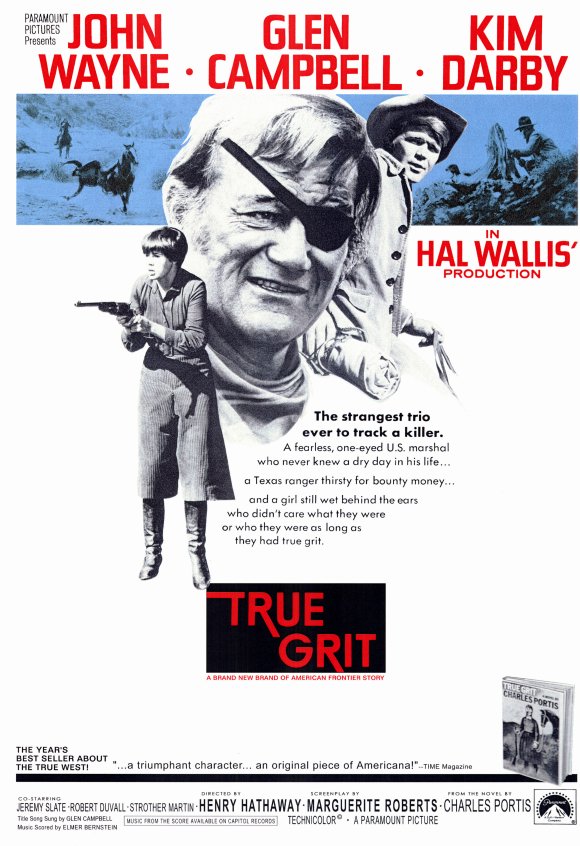

It’s clear from the start in the film where the friendship between the teen-aged Mattie Ross and the grizzled frontier marshal Rooster Cogburn is going. It’s a pleasure to watch it go there, but one can’t fully enter into the journey as a participant. John Wayne, who won his only Oscar for his portrayal of Cogburn here, is exceptionally good, working against his usual buttoned-up hero’s persona, but reveals the character’s decent and genial side too quickly.

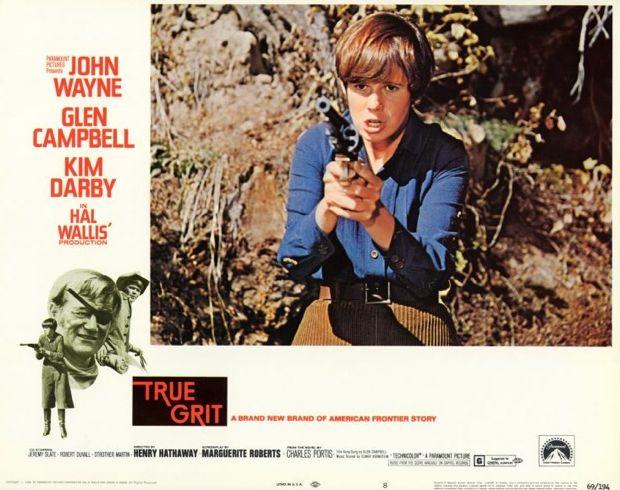

Kim Darby, as Mattie Ross, also gives a fine performance, but because Darby was 21 when she made the film, Mattie’s precocious self-possession can’t help but lose some of its edge. (In the book, Mattie is 14.) Glen Campbell, then a popular cross-over country singing star, was cast in the third lead as Le Boeuf, primarily as a marketing ploy one assumes. He acquits himself well enough, but always looks out of his league among the other fine supporting players like Robert Duvall, Dennis Hopper and Strother Martin.

Although Hathaway directs the film in a classical style, with beautifully composed images (discounting a few ill-advised zooms), the film tries in other ways to be contemporary. Elmer Bernstein’s score, often echoing the one he did for The Magnificent Seven, is generally light and buoyant — it doesn’t enforce the darker emotional currents of the tale. The script incorporates a lot of Portis’s fine dialogue but emphasizes the cheerful and comic side of the novel, at the expense of its paradoxes and contradictions. The disturbing undertow of the book is only suggested.

Paramount probably thought it was taking quite enough chances on this film, a Western with a strong female protagonist that featured John Wayne as a slightly less than heroic drunk — but in truth it was only keeping up with the times. In the 1960s, Hollywood and the culture were becoming self-conscious about the conventions of the Western in an era of national doubt about the American dream, undermined by a controversial war in Vietnam and rowdy social upheavals at home.

1969 also saw the release of The Wild Bunch, Sam Peckinpah’s savage and cynical deconstruction of the Western genre. True Grit was a big hit at the box office, The Wild Bunch not so much, but a critical favorite. The culture was clearly open to a different kind of Western. It’s a shame that filmmakers chose to follow in Peckinpah’s tracks, instead of Hathaway’s or even Portis’s. Dark and unconventional as the novel True Grit was, it still managed to celebrate, in its quirky way, the humane and noble values of the classic Western, introducing a convincing female perspective in the process. Portis’s vision might have led to a renewal of the Western film — Peckinpah’s led to its virtual destruction as a reliable Hollywood genre.

Well put.