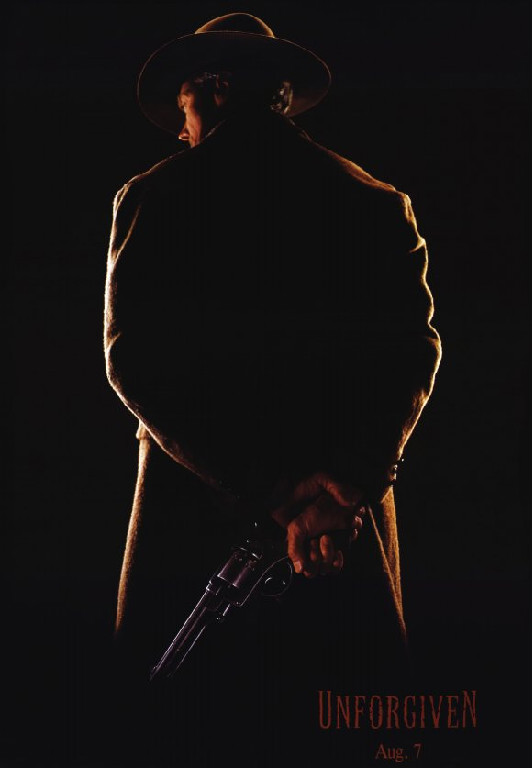

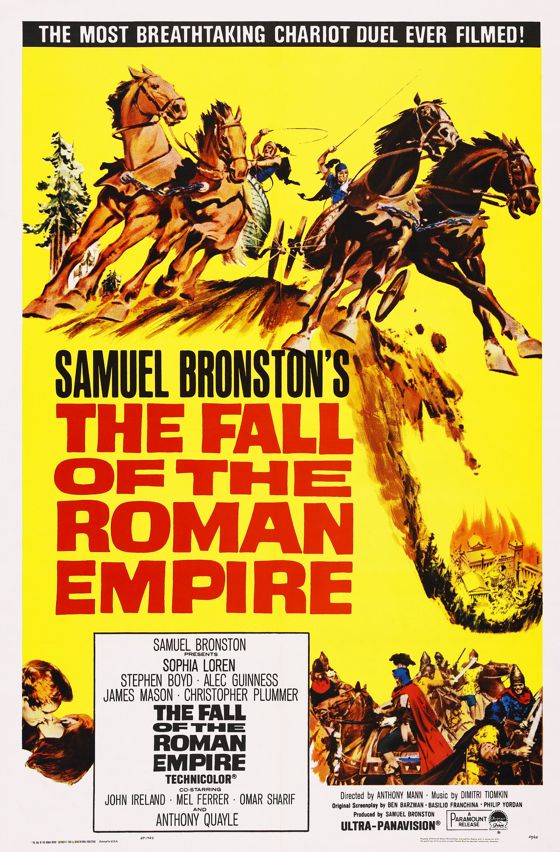

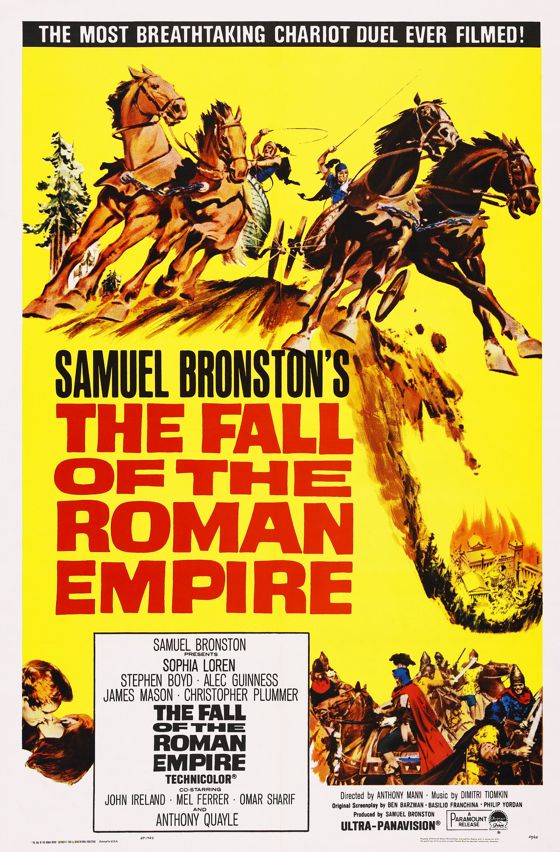

Magnificent in many ways, breathtaking visually in many sequences, Anthony Mann’s The Fall Of the Roman Empire, from 1964, is nevertheless an epic failure. Unlike the Roman Empire, the film’s downfall can be traced to a single cause — a single miscalculation in casting. A film as big as this needs an emotional rudder, a figure at its center the audience can steer by, and Stephen Boyd is just not able to be that. Very few actors could, but Boyd is singularly ill-equipped for the task.

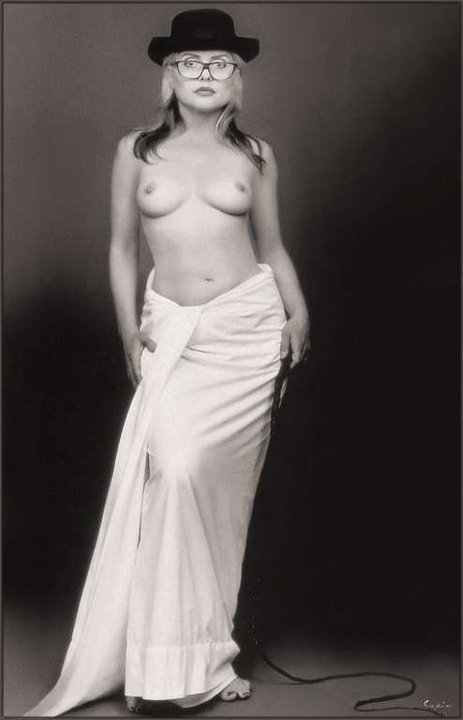

Boyd had a slightly fey quality, a hint of weakness in the eyes and mouth, which worked wonderfully when set against the stolid heroism of Charlton Heston in Ben-Hur. It fueled the slight suggestion of a homo-erotic attraction between the two antagonists. As the heroic lead of The Fall Of the Roman Empire, by contrast, Boyd creates a kind of black hole of charisma at the center of the picture, especially since he is paired romantically in the story with Sophia Loren, who is, just in her own person, an epic of femininity. Between the Roman Empire and Loren’s empire of female flesh, Boyd doesn’t have a fighting chance.

Boyd was an actor of limited range, and heroic grandeur did not fall within it, as it did for Heston, limited as Heston may have been in other ways. (Heston and Kirk Douglas both turned down the Boyd role — either one of them, I think, could have saved the picture.) Boyd here summons at best the slick authority of a Las Vegas lounge singer — not someone one would entrust with the command of a Roman cohort, much less the rule of Rome itself. It doesn’t help that Boyd is given a preposterous hair-do, with curled, poofy bangs, obviously dyed. If this film hadn’t cost so much money, you might almost believe that the bangs were some kind of cruel joke slipped into the film by a prankster on the production.

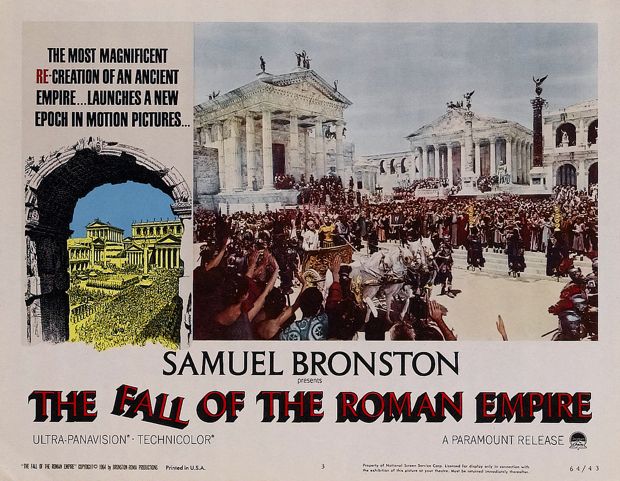

The inadequacy of Boyd can’t quite sink the first half of the film, up to the intermission. This section, set on the frontiers of the empire in Germania, boggles the mind with its size and sweep and beauty. We will never again, in the age of CGI, see images like this on film.

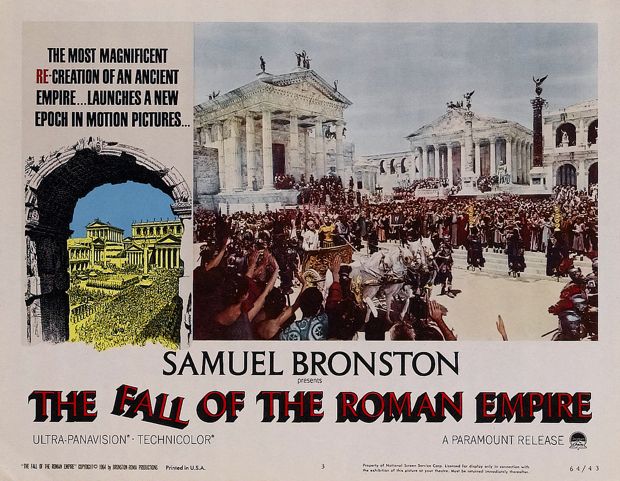

The film shifts to Rome after the intermission and, despite a parade of staggering and mostly magnificent sets, unravels quickly as a drama. It becomes a test of wills between the neurotic Caesar Commodus, played with relish and wit by Christopher Plummer (below) . . .

. . . and Boyd’s Livius, his second in command. At stake is Livius’s love for Lucilla, Commodus’s sister, played by Loren, as well as the survival of the Roman Empire. It’s hard to care about either with Boyd as the protagonist in both struggles and a bit of a relief when Rome finally implodes.

Once you accept the film as a failure, though, you are free to appreciate its wonders — some of the most spectacular recreations of the ancient world ever committed to film, all shot with Anthony Mann’s usual genius for plastic composition and action. It’s a thrill, as well, to watch the way the camera worships Loren, who gives a very good performance here, along with a wonderful cast in almost all the supporting roles. Fans of Ridley Scott’s Gladiator will also discover that its original screenwriter David Franzoni found much of his inspiration for that film in The Fall Of the Roman Empire, set in the same period, with a number of set pieces and major story elements in common.

But, as I say, Mann’s film is a rudderless ship, narratively and emotionally — one soon ceases to wonder where it’s going, because, like the Roman Empire itself in its twilight years, it’s so obviously going nowhere.