Nothing says “Christmas” like a lot of half-naked women.

Nothing says “Christmas” like a lot of half-naked women.

By John Falter, who had a way with holiday themes.

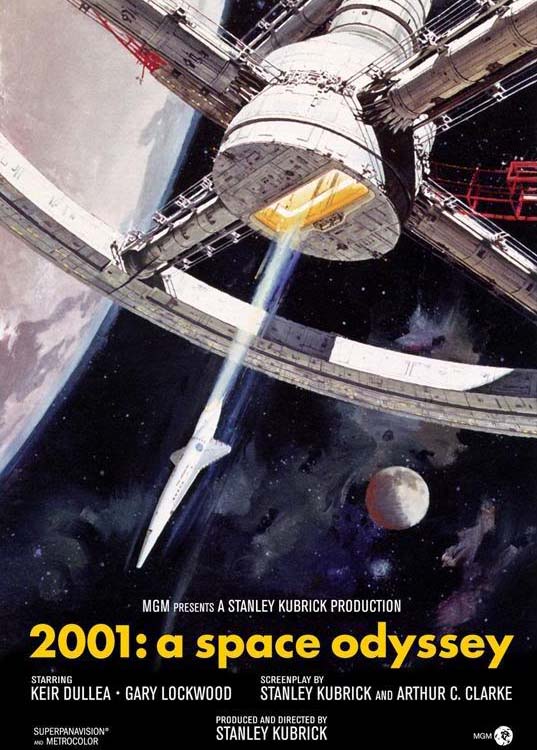

The dramatic narrative of Stanley Kubrick's legendary space epic is meager, to say the least. Crisply told, it could fit easily into a half-hour episode of The Twilight Zone. Its core is a duel to the death between two somewhat mechanical human astronauts and an all too human computer on a mysterious mission to Jupiter. The first 54 minutes of the film are, in story terms, pure exposition, which might have been delivered in a few minutes. The last 25 minutes pay off the Jupiter mission, but not in narrative terms — the climax of the “odyssey”, and the discoveries that prompted it, remain mysterious, unexplained. There is no dramatic denouement.

Half the film is thus in essence about something other than drama, other than narrative. It's about situating us imaginatively in time and space. The first 20 minutes of the film take place in prehistoric times, and illustrate man's discovery of tools — which he turns instantly into weapons. The boldest jump cut in all of cinema takes us from a prehistoric weapon spinning in the air to a space ship circling the earth to the strains of a Viennese waltz. The suggestion is that all human achievement in the interim has been of a piece. Man the maker has used his toolmaking skills to create art and technology, but these are merely elaborations of a single phenomenon.

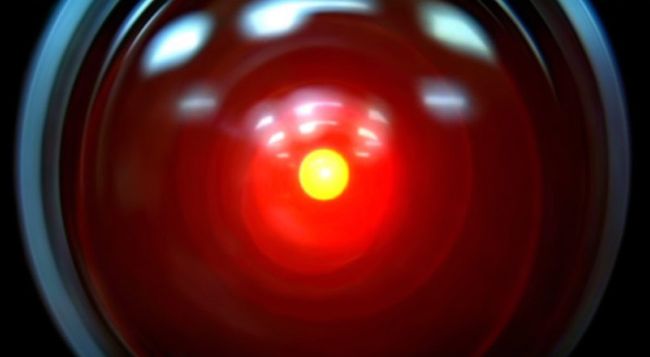

Indeed, it turns out that the most advanced technology in the film, the HAL 9000 computer that controls every function of the space ship heading towards Jupiter, is also a weapon, a killing machine — an attribute that seems intrinsic to its nature as a tool. It cannot help but incarnate the murderous instincts of the species that made it. When Dave the human astronaut defeats and lobotomizes the computer, it's easy to see this as a kind of metaphorical rejection of technology itself, linked as it is to mankind's murderous proclivities.

Having made this leap, Dave is taken on a mystical journey of rebirth, which presumably will mark a new stage in mankind's development, one as portentous as the one marked by the original discovery of tools.

Both of these turning points of development are accompanied by the appearance of a black monolith, a token it would seem of some higher life form which is prompting man along in his evolution. The monolith is something of a red herring, however. It is never explained, the life form it represents is never shown. It thus becomes merely a suggestive emblem of evolution, or perhaps an admission that the agency of evolution cannot be explained.

What the film is really doing is, as I say, situating us in time, asking us to be aware of our place in time, in a particular stage of human development. The prehistoric era is distant enough that the discovery of toolmaking seems somewhat fantastic, just as the year 2001 was distant enough from 1968, when the film came out, to make the imminent ramifications of technology seem fantastic. But we recognize all too well the violent nature of early man, just as we recognize all too well the bland efficiency of the corporate man of 1968, projected slightly into the future.

What makes the film a film, in the end, instead of an illustrated lecture on philosophy, is the way Kubrick situates us in its imagined spaces — on the African savannahs where early man emerged, on vehicles commuting to the moon, on the moon itself, on a craft penetrating deeper into space . . . even projecting us, at the end, into the unimaginable future.

The meticulous, slow-paced exposition of the film's first hour doesn't read as exposition — it allows us to experience viscerally a routine trip to the moon. The deliberate pace of the duel on the space ship traveling to Jupiter puts us aboard that ship and makes it an environment we can imagine inhabiting. The mind-bending visuals at the end allow us to feel, if not understand, what confronting a new stage of consciousness might be like.

Kubrick is using the full resources of cinema in the service of his philosophical meditation on the state of human development. The red-herring mystery of the monolith, the dramatic suspense of the duel with the computer, supply just enough of conventional movie narrative to string us along on what is essentially an intellectual journey.

Kubrick's intellectual meditation will seem trite if reduced to words alone, but Kubrick puts us into spaces, into seductive environments, in which we ourselves can meditate, internalize for a time the truths Kubrick wants us to entertain, evaluate their resonance within our own imaginations.

In the 1960s, only Godard was making films as radical, conceptually, as 2001. It remains astonishing that 2001 was financed by a major Hollywood studio. Ironically, it was only the resources of a major studio that made Kubrick's conceptual experiment possible, by giving him the money it took to make his imaginary spaces plausible. If they had not been plausible, the film would have been the most boring and superficial slide lecture in the history of movies, instead of what it is — a singular experiment in cinema that still points the way to uncharted possibilities for the medium.

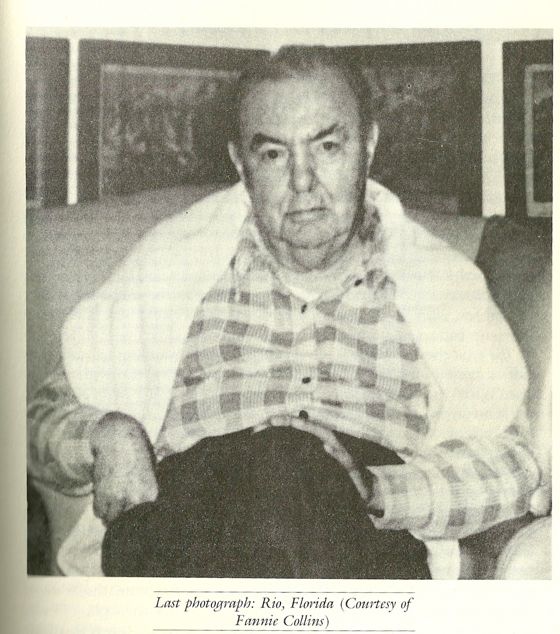

Above is the last picture taken of James Gould Cozzens, in the Florida

condo where he lived with his wife from 1973 until his death in 1978.

As readers of Paul Zahl's posts on this site (in The Zahl File) will know, Cozzens had been a major literary celebrity in the 1950s and a

best-selling author, but some unpleasant (and inaccurate) reports of

his personal prejudices along with shifting tastes in literature left

him all but forgotten at the end. He's probably best known today as

the author of By Love Possessed, which was made into a Hollywood film.

Below is a photograph of the condo as it stands today, taken a few days

ago — the date-stamp is wrong:

[Photo © 2010 Don Whalen]

It's at Beacon 21, Rio (Jensen Beach), Florida. When Cozzens moved there

permanently from New England, he sold his large library and basically

stopped writing, except in his diary. He puttered in a small garden

attached to his condo and watched TV.

He was especially fond of The Mary Tyler Moore Show and also got into

the Watergate hearings.

The New York Times was on strike when Cozzens died, so he never got a proper

obituary there. The obituary in his local newspaper was terse, and

described him this way — “He was a distinguished writer and author,

and was an Army Aviation

Corps veteran of World War II. He was of the Episcopal faith.”

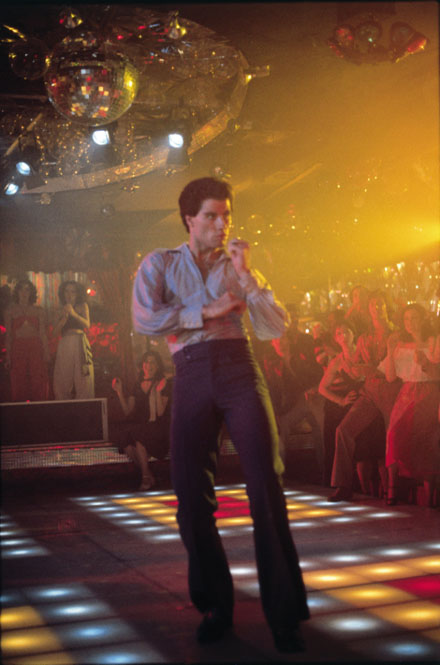

The times for local movies were printed directly beneath the obituary

— playing that week were Saturday Night Fever, Star Wars and Jaws

2.

Paul Zahl, on whose research the above is based, and whose friend Don

Whalen took the contemporary photo of the condo complex, says that

Cozzens was actually more of an Episcopalian agnostic, verging on

atheist. Paul also notes the echo of Jack Kerouac's last isolated days

in Florida — Kerouac watched a lot of TV, too. He was fond of The

Beverly Hillbillies.

American writers often come to strange ends — but then, so do most of us.

[Go here to see a piece Paul wrote about Cozzens's earlier home in

Lambertville, New Jersey — a long way from Jensen Beach.]

. . . directed and animated by Kendra Elliott — an amazing piece of work.

Check it out here:

“Twilight Lovebite” by Lavalier

On his last night in Las Vegas my friend Jae and I went downtown to the El Cortez casino — still the saddest, strangest, cheapest and most wonderful casino in Sin City, especially during the Christmas season.

I played dollar roulette for about an hour and broke even, then lost $20 at craps. Later that night, at a bar, I hit four tens on a video poker machine (with a 25-cent bet) and won $12.50. A fun night of gambling with free drinks which cost me less than ten bucks.

Jae lost $12 at roulette and $20 at craps, then won $64 dollars at blackjack, for a profit of $32.

Ah, Las Vegas, when the high rollers step out . . .

[A note: 83,000 visitors to the site last month, most just passing through, I'm sure, looking for images, but still a record.]