Captain At Sea by Anton Otto Fischer . . .

Captain At Sea by Anton Otto Fischer . . .

A Moment Of Pleasure

Strawberries — yum!

A Kiss Goodbye

As I recall, they were all pretty much like this — though it's possible my memory is playing tricks on me . . .

[Image by Glen Orbik]

Most B-movie Westerns were done as parts of series featuring a star and

recurring actors in supporting roles, often a comic sidekick but

sometimes a musical sidekick, if the star wasn’t himself a singing

cowboy. The bad guys and the female romantic leads changed from

picture to picture.

When RKO set Tim Holt up as the star of his own B-Western series in the

early 1940s, they gave him a comic sidekick and a musical sidekick.

Even when a B-Western star didn’t have a musical sidekick, musical

numbers were usually a part of the formula in the 1930s and 1940s, and

they were usually anachronistic — Western Swing numbers written for

the films rather than authentic cowboy songs.

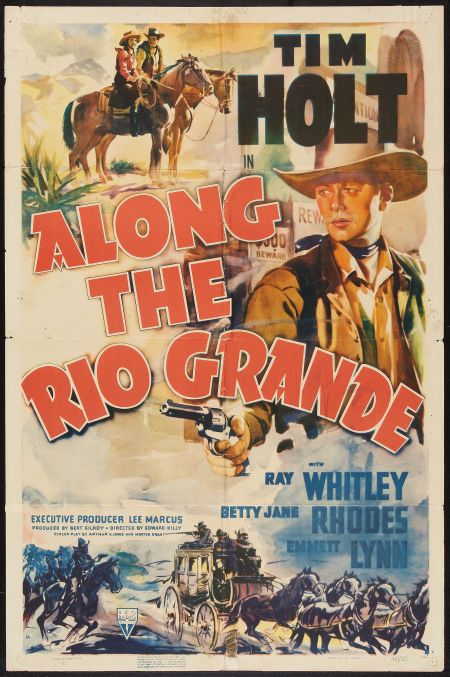

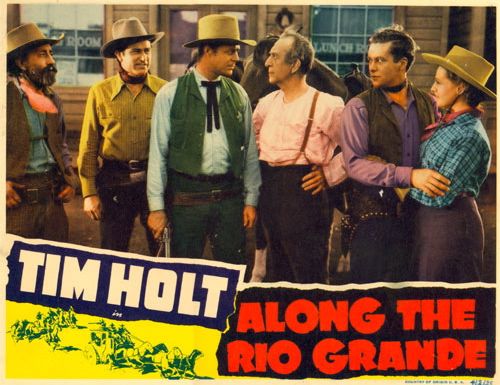

Along the Rio Grande, from 1940, is the first film in the new Tim Holt B-Western

collection from The Warner Archive which features Holt in the starring role. It was, I believe, the third B-Western in which he starred. (He had earned his spurs before this playing second leads to more established B-Western stars.)

These early Holt Westerns play like variety shows rather than dramas.

Dramatic exposition and action sequences alternate with musical numbers

and comedy bits in a regular pattern. In a way they harken back to the

Western arena shows of the 19th Century, which were essentially variety

shows with a Western theme, mixing staged dramatic spectacles — mini-narratives, like the attack on the stagecoach, on the settler’s cabin — with self-contained acts featuring theatrical displays of marksmanship and horsemanship, all knitted together with musical

interludes.

A little something for everybody was the idea in most B-Westerns, too — all of a simple and unsophisticated nature, reflecting the primary audience for these films, kids

everywhere and older folks in the smaller towns and rural areas.

The variety is what keeps the films enjoyable even today. The

conventional plots and merely serviceable acting couldn’t sustain them

as works of drama, but (as was true in vaudeville, or Buffalo Bill’s

Wild West) you always knew there was going to be a change of pace soon

— another routine by the comic sidekick, another song, another awkward

but charming interchange with the leading lady, another thrilling chase

on horseback.

There’s usually a lot of entertainment packed into these short films —

modest, perhaps, but pleasantly varied. The horsemanship is always

first-rate, though, and if all else disappoints, you rarely have long

to wait before someone says, “We’ve got to head them off at the pass!”

. . . at which point the screen will explode with beautiful images of

beautiful animals galloping through scenic landscapes, with heroic

figures in the saddle, bent on righting one wrong or another. If for

nothing else than this, the B-Western remains a delightfully dependable

form of amusement.

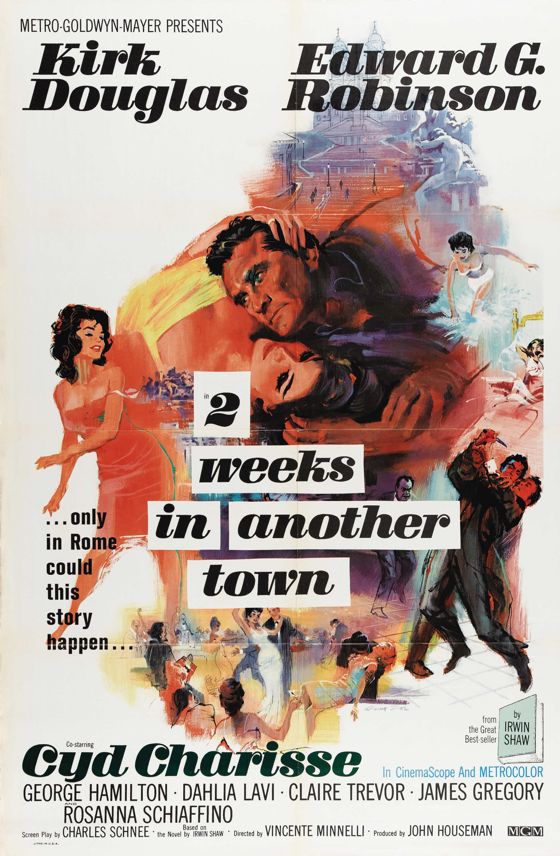

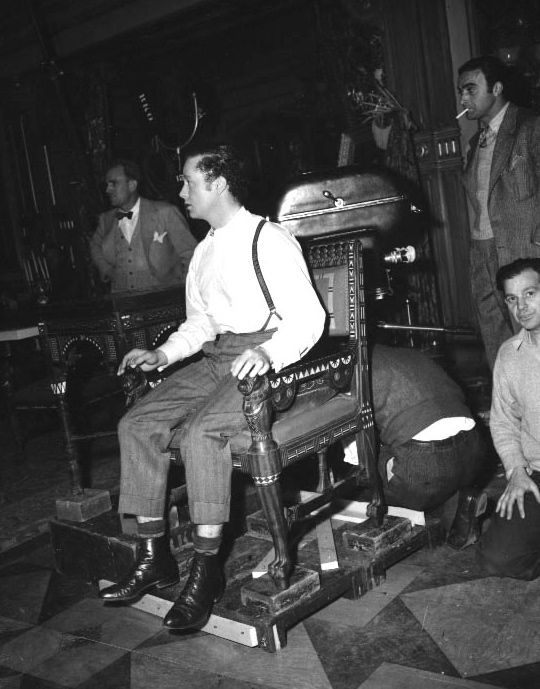

Many people know The Bad and the Beautiful, Vincente Minnelli's classic melodrama about the film business, from 1952, produced by John Houseman and starring Kirk Douglas, with a script by Charles Schnee, based on a story by George Bradshaw.

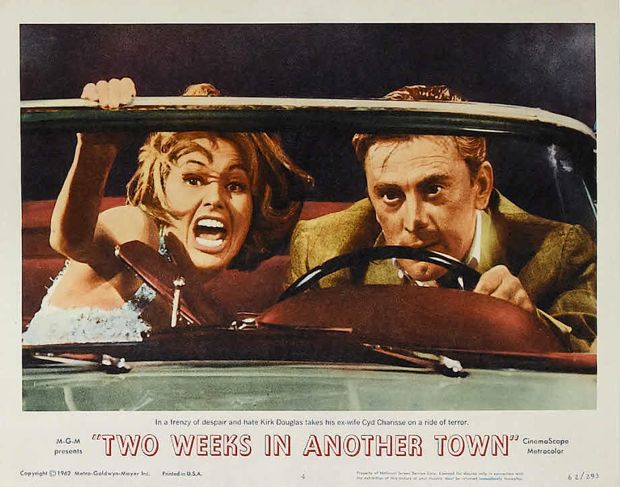

Ten years later, Minnelli, Houseman, Douglas and Schnee tackled the same subject again, in their adaptation of Irwin Shaw's novel Two Weeks In Another Town. The second film is much darker, and less well known — it flopped at the box office and was only released on DVD this year, by The Warner Archive.

Long known as a kind of lesser pendant to The Bad and the Beautiful, it has nevertheless found champions among admirers of Minnelli's work, and is by far the greater film — one of Minnelli's masterpieces.

I have written before about my problems with The Bad and the Beautiful (above) — for my views on it click here — but they boil down to my mistrust of the film's self-congratulatory message. It displays a gallery of glamorous but despicable characters, lets us relish their savaging of each other, but ultimately asks us to admire them as noble monsters for their dedication to the art of film. The Bad and the Beautiful all but suggests that their egomania and meanness are required attributes for those who serve the celluloid muse.

When artists excuse the bad behavior and character flaws of artists in this way, we have a right to be suspicious of their motives, to resent the self-serving nature of the enterprise, which may be telling us more about the artists who actually made the film than about the nature of artistic creation.

Two Weeks In Another Town is a much more mature and honest work. It's a descent into the hell that the film business really is — a hell in which personal betrayal and selfishness serve only as tokens of power, not as the means of artistic accomplishment. It charts the personal cost of the industry's meanness, not to its obvious victims, the system's losers, but to those who exercise their power for show, to demonstrate prestige — in short, to the “winners”.

All the industry professionals featured in the film have shriveled souls, live in a state of existential terror. As they howl on the margins of nonentity, they look about desperately for one last target, one last peer to hurt and humiliate, as though they might recover their sense of self in the act.

It's truly terrifying, and only two people escape from this version of the wreck of the Pequod — a young actor embarked on a self-destructive binge and the older actor who jerks him out of the whirlpool at the last minute, because he's been there himself and knows what it feels like to drown.

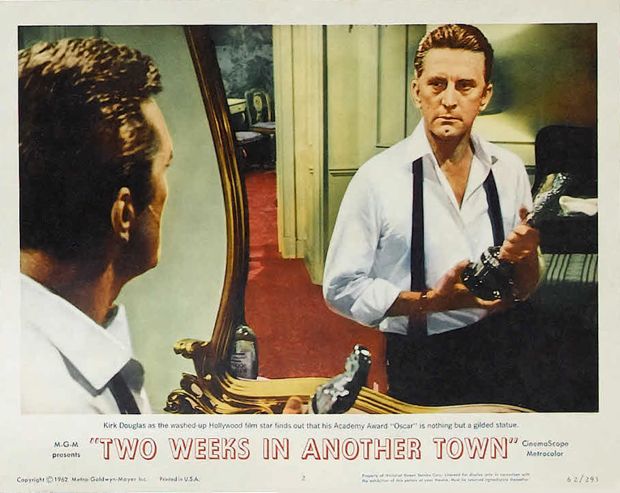

Kirk Douglas, in one of his greatest performances, plays the older actor. We meet him as he hovers near rock bottom as a man and an artist, his life and his career in shambles. Finally hitting rock bottom on location in Rome, in a desperate bid to salvage his career, is what saves him. It's when he gives up on recovering his past that he finds a way to the future. It's a powerful tale, but not very pleasant, and one can see why audiences rejected this look at the dream factory without illusions. We really don't want to see too much of that man behind the curtain, especially when he turns out to be a vicious jerk.

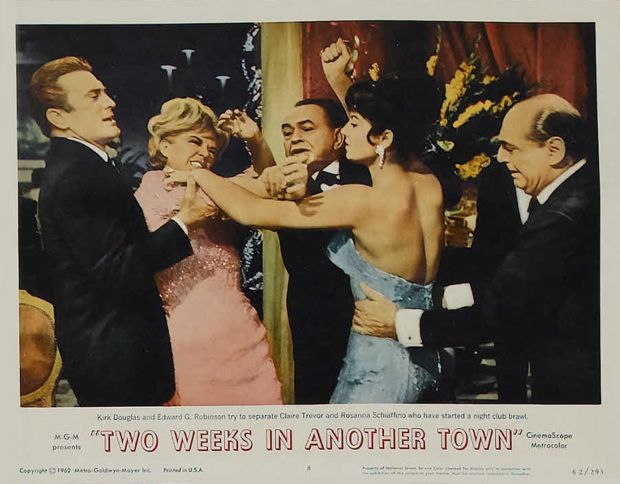

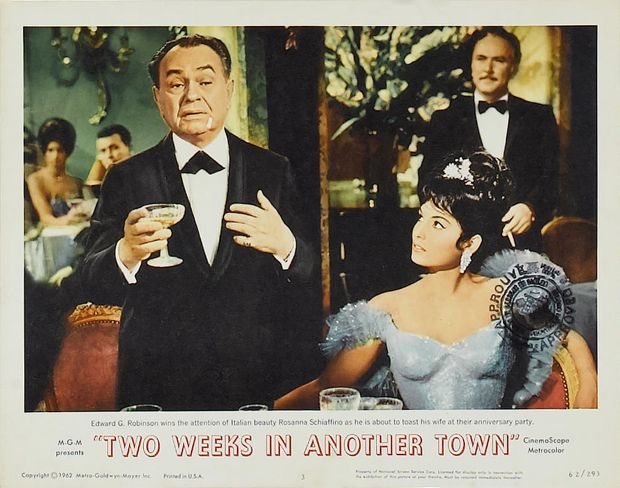

Two Weeks In Another Town may be the best movie ever made about the film business, and it's definitely one of Minnelli's most beautifully crafted films, with consistently inventive use of the Cinemascope frame and of lurid colors that mirror the lurid recesses of the Hollywood soul. The acting is uniformly fine, even from George Hamilton doing a pretty good impersonation of James Dean. Minnelli got Edward G. Robinson to give a restrained performance, and Cyd Charisse an unrestrained one — extraordinary accomplishments. Charisse has an episode of hysterics in a speeding car that will chill your blood.

The Bad and the Beautiful is more satisfying, the way a lie can be more satisfying than the truth — for a while, anyway. The later film is two weeks in another town altogether — the real town of Hollywood, which can't escape itself even when it goes on location in Rome.

Of the many pleasures B-Westerns can deliver, not the least of them is incoherence — both narrative incoherence and conceptual incoherence. These movies were made quickly, to fill out release schedules. “Elements” — stars, character types, action sequences, themes, locations — were taken from an existing pool and sometimes thrown together illogically, just to get something in the can and out to theaters in time for next Saturday's matinee.

The results can be oddly exhilarating.

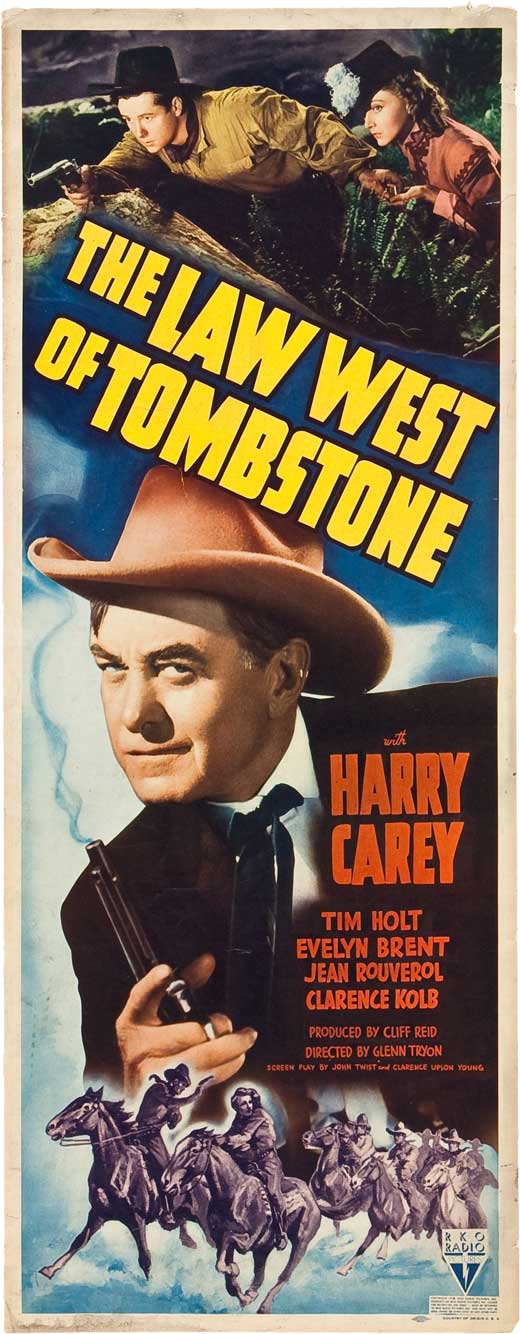

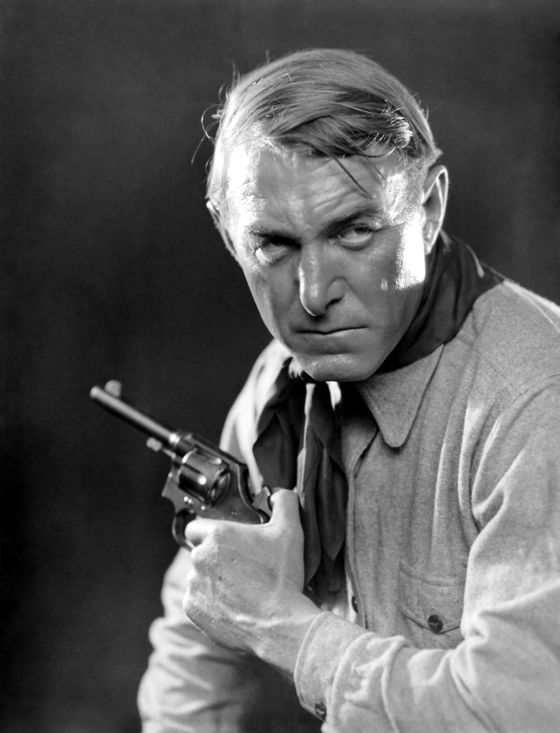

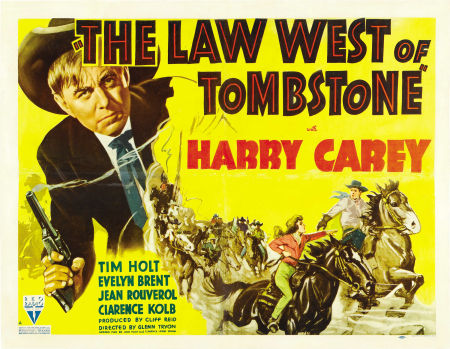

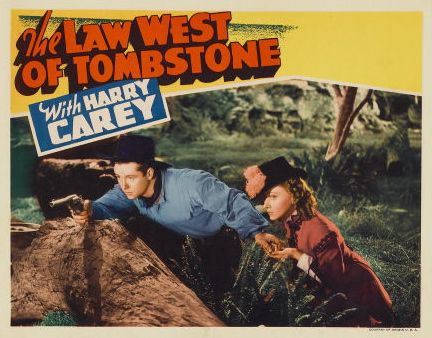

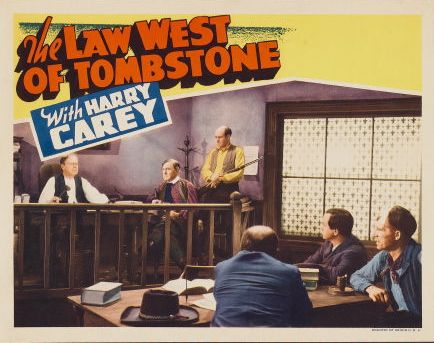

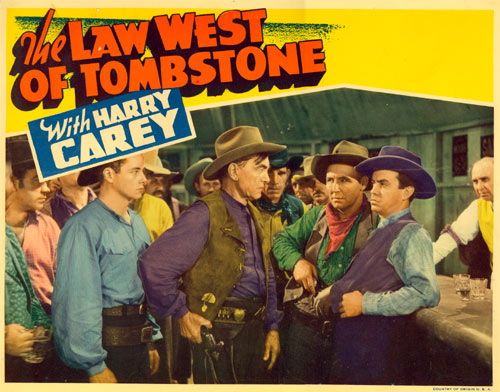

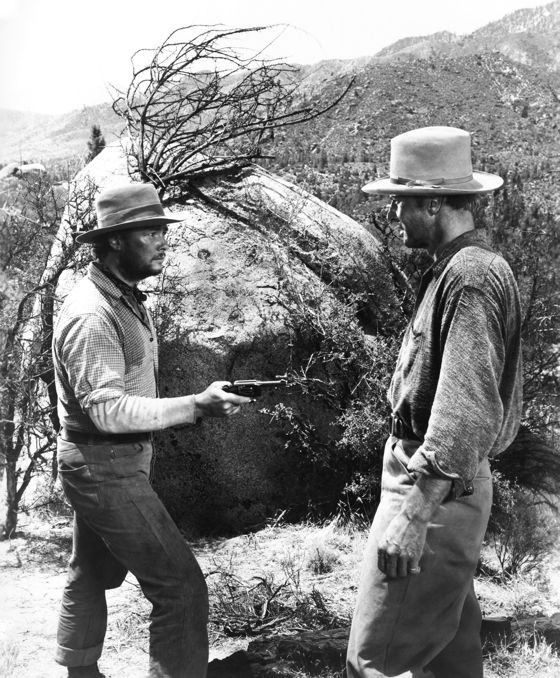

A case in point is the second film in the recently released Tim Holt collection from The Warner Archive, The Law West Of Tombstone. Holt plays the second lead here in a film starring Harry Carey (above). Carey was a big Western star in the silent era, most famous for his collaborations with John Ford, and he still had enough of a following to allow him to carry a B-Western well into the 1930s, but he was getting too old to play a traditional leading man by the time this film was made, in 1938.

The solution was to make Carey a kind of featured character actor, and to let the much younger and more vital Holt handle the romance and the big action sequences. It was all part of a process — Carey's name and his reputation as an authentic Western star sold the picture to aging fans of the genre, even as Holt was being groomed as a Western star in his own right, someone who could appeal to the younger fans.

The sequences featuring Carey and the sequences featuring Holt have not been fully integrated with each other. You get a sense that they were conceived separately and then cobbled together without regard for dramatic consistency. Carey is introduced in New York, running an improbable scam on a wealthy Easterner, then shuttled back to the West where he's soon sentenced for another scam, and given a reprieve in return for bringing the “Tonto Kid” to justice.

Holt plays the Tonto Kid, and the Carey character has no intention of bringing him to justice — he actually wants him to marry his daughter, who doesn't know she's his daughter. The daughter is engaged to marry the Tonto Kid's partner in crime, who's a genuine bad guy. The Tonto Kid kills him in self defense in a bar fight, but the daughter thinks it's a case of murder. “You killed him!” she screams at Holt. “Yeah,” Holt says, with a casual “so what?” look on his face.

At this point, the plot transforms itself into the tale of a range war between some local ranchers and a tribe of Indians being manipulated by corrupt agents. Did I mention that the Carey character has a pet monkey?

It's all quite mad.

In the midst of the muddled melodrama, there's a train robbery, preceded and ended by stunning shots of the robbers, Holt and his partner, boarding and escaping from the train — off of and onto the backs of horses running beside the train. These are shot from the platform at the back of the train in single takes, without stunt doubles. The images are incredibly exciting and beautiful, and when you're watching them you just don't give a damn about the plot anymore. On some level they justify the whole film.

Fans of Josef von Sternberg's silent films will be tickled to see Evelyn Brent, who starred in two of them, featured in The Law West Of Tombstone in a

supporting role as an aging gold-digger, who's an old flame of the Carey character — another nod, perhaps, to the audience's nostalgia for the silent era. There are echoes within echoes in the Western genre here. In von Sternberg's film Underworld, Brent plays a character called “Feathers” (above), the nickname given to the Angie Dickinson character in Rio Bravo in homage to the earlier film, from which Hawks also borrowed the spittoon gag in the opening scene with Dean Martin. And in the last shot of The Searchers, John Wayne delivers one of Carey's signature gestures, grabbing on to his left arm with his right hand, as an homage to the late Western star. Carey's son Harry Carey, Jr. appears in many Westerns by Ford and other directors, including Hawks, and Carey's widow Olive Borden appears in The Searchers.

If The Law West Of Tombstone had been made last year, we might be tempted to read it as a deconstruction of the B-Western form, and to find the exercise extremely witty and sophisticated, charmingly surreal. Audiences of the time may have experienced it in much the same way, as an incoherent but delightfully demented compilation of familiar elements — a kind of freewheeling jumble with its own bizarre integrity, like a pile of pieces from a disassembled jigsaw puzzle. You enjoy each element for what it is, and your enjoyment becomes the film's organizing principle, in the absence of any other.

If you're not a fan of B-Westerns, it's probably impossible to explain their appeal to those of us who really love them. Their plots tend to be simple, some might say simple-minded, with cardboard-thin characterizations and clumsy dialogue. The acting can be clumsy, too, even by good actors — it's hard to speak clumsy dialogue with conviction. And yet . . .

. . . they tend to be beautifully photographed, at least in the outdoor scenes, with regular displays of superb horsemanship. Indeed, the action sequences on horseback are at the heart of these films, and like the transporting arias of operas with dumb plots, they can redeem much. (It's no accident, I think, that Westerns used to be called horse operas.) Technically impressive in so many departments, they still have the air of being made casually, by people who are enjoying themselves. They mix elements with insouciant ease — introducing songs at the drop of a Stetson, or outlandish costumes that clash with more authentic gear.

They were the testing ground for actors being groomed for stardom, as well as the dumping ground for stars who'd fallen from the industry heavens. You have the pleasure of seeing familiar faces working up their chops at the beginnings of their careers, and old favorites respectably earning paychecks on their way out.

The Warner Archive has just released a ten-film collection of B-Westerns featuring Tim Holt — one of the most appealing of B-Western stars. Holt appeared in a handful of films that must be accounted among the greatest ever made, like The Magnificent Ambersons (above) and The Treasure Of the Sierra Madre (below), but he was never comfortable in Hollywood and had no great ambitions to be a star.

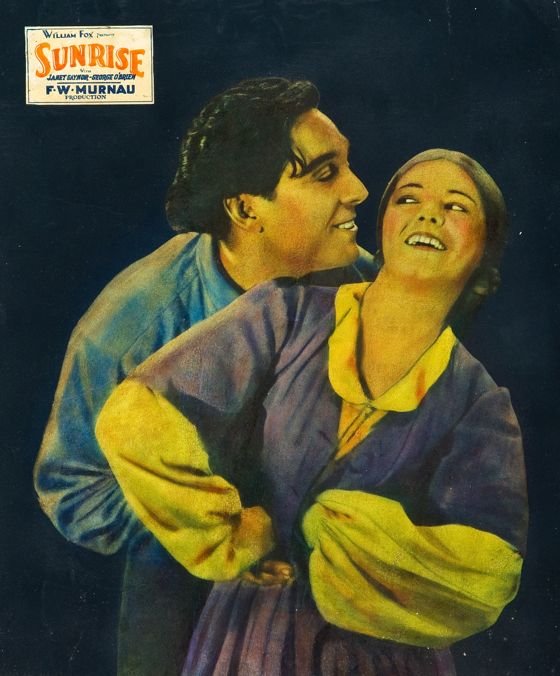

He liked horsebacking, though, and seems to have been content to grind out B-Westerns in rustic places far from Gower Gulch. He started out playing second leads in such films — like the earliest one in the Warner Archive collection, The Renegade Ranger, from 1938, which stars George O'Brien, who achieved screen immortality in the silent era in films like Sunrise and The Iron Horse.

In The Renegade Ranger Holt plays a callow, peevish youth with a dose of innocent charm, which will remind viewers of his role in The Magnificent Ambersons. He's much more comfortable in these surroundings than O'Brien, who seems a bit out of place in a talking picture, delivering his lines awkwardly but still managing to come across as a hell of a nice fellow. It's easy to see why Holt would later be tapped to star in his own series of B-Westerns.

Rita Hayworth plays the female lead in the picture — a Spanish-American outlaw who makes her first appearance in a black silk blouse, trousers and a Gaucho hat, brandishing a six-shooter. The outfit is delightfully surreal and vexing. Hayworth delivers her lines stiffly but carries herself like a star, as trained dancers often do. Just watching her move onscreen is captivating.

The film takes the side of Spanish-American ranchers whose land is being stolen from them by corrupt politicians — this is what has set the Hayworth character against the law. There are no stereotyped banditos in sight, which is refreshing, and must have been gratifying to Miss Hayworth, herself of Spanish heritage.

There's a lot of galloping around, a lot of shooting, a few songs, including a Western swing number, and a Spanish dance (not by Hayworth) with castanets. The plot resolves itself predictably. There is nothing much at stake in the drama beyond some misunderstandings that are easily resolved when the time comes for them to be resolved.

But, boy, what fun it all is.

Cool.

A Study Of Drapery, 1900

By Edmond Gray . . .