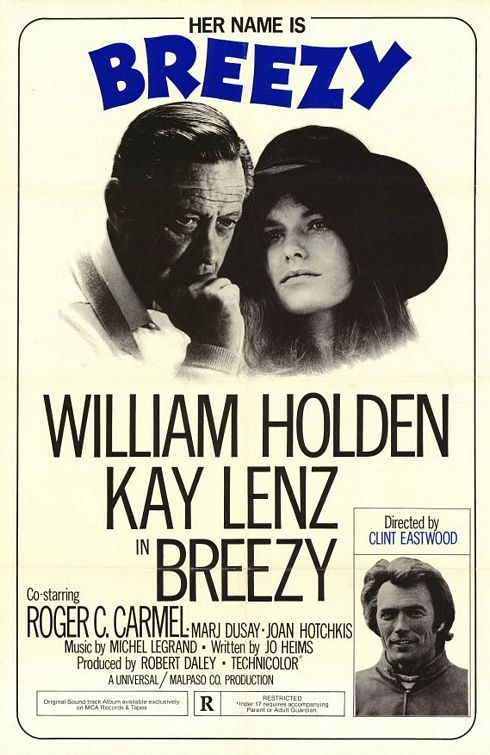

How do you portray a convincing love story between an 18 year-old woman and a 50-something man — one that isn’t totally creepy? Somehow Clint Eastwood pulled it off in Breezy, the third film he directed, in 1973.

It helps if the 50-something man is played by William Holden, still in good shape at 55, devilishly handsome and charming, and the woman is played with impeccable intelligence and poise by Kay Lenz, 20 when the film was made.

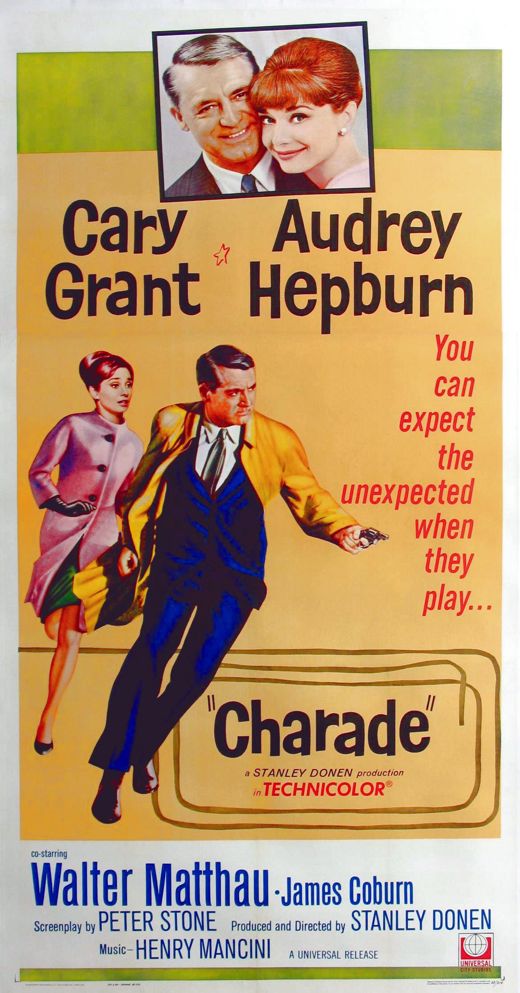

Cary Grant intuited the basic strategy when he starred, at the age of59, opposite Audrey Hepburn, 34, in the film Charade. Grant insisted that the script be rewritten, based on that casting, so that he never at any point was seen to be chasing after the Hepburn character. Every

romantic or sexual move had to be initiated by her. Grant couldn’t chase, but he could be caught, if it was clear that the woman was in charge every step of the way.

This is not how a romantic leading man normally wants to be portrayed in a love story, but in this case Grant felt it would be crucial to selling the relationship. It required Grant to substitute a delicate wit in the place of virile aggression, in deflecting her advances, and it required Hepburn to substitute a bolder kind of wit in the place of seductive elusiveness.

This is the dynamic employed in Breezy. The young woman, Breezy, is the seducer — the older man resists. It becomes a battle of wits, with high stakes — character and soul.

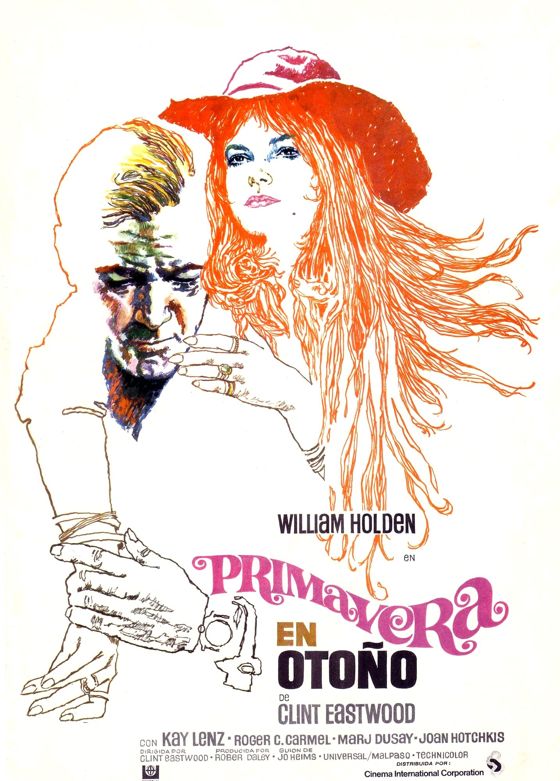

Breezy goes Charade one better, though, by making the young woman far more mature, emotionally, than the older man. Part of her seduction lies in exposing his puerile defenses against feeling, against emotional commitment. In the process, everything gets turned on its

head.

The woman stays in charge, but the man seduces her in return by his appreciation of and respect for her wisdom. This is closer to what is probably the typical dynamic of a love affair than most films ever get, but in Hollywood it seems to happen only when the man has the built-in power advantage of age, so that his sensitivity doesn’t unman him.

Watching a film like Breezy, where the age difference between the lovers is actually unsettling, makes you realize how cavalierly Hollywood takes the older-man/younger-woman model when the age difference isn’t so extreme. It’s normally all about the fantasies of older men, in which women are the trophies of power. As it happened, the executives at Universal, which made Breezy, didn’t like the film Eastwood delivered and dumped it without any promotion. It never found an audience — and maybe there wasn’t one. Maybe nobody wanted to see a film in which the price of some young tail was so high.

Breezy offers her older man sex up front, but she also makes him want to be worthy of her, sending him on a journey of self-discovery that is difficult and painful. She knows exactly what she’s asking, too, and she asks it because she sees something in him that he doesn’t see or has lost . . . and she trusts him to find it, trusts him to grow up.

By an unusual and improbable route, Breezy becomes a real love story — not the self-congratulatory male fantasy the Universal executives probably thought they were buying.