As I’ve written before, Baudelaire saw the world, at its best, as an inn.

I see Las Vegas as a phantasmagorical rendition of that idea into an

urban space, and an urban ethos. It’s also possible to see the

phantasmagorical aesthetic of Las Vegas as a radical critique of 20th

Century art, 20th Century fine art, in particular, which perhaps

strayed too far from the auberge.

The idea of art itself as a kind of inn is not new. In his preface to “Tom

Jones”, way back in the 18th Century, Henry Fielding says that “An

Author ought to consider himself, not as a Gentleman who gives a

private or eleemosynary Treat, but rather as one who keeps a public

Ordinary, at which all Persons are welcome for their money.”

(Eleemosynary means charitable, and a public Ordinary is of course a

public tavern — a pub.)

The fine arts in the 20th Century, alas, out of a kind of decayed

Romanticism, a puerile rebellion against Victorian forms and an often

hypocritical reaction against commercialization, became a hermetically

sealed system, which the public was not invited to enter — popularity

was considered demeaning and art itself became a specialized realm

which the ordinary person could approach only as a supplicant, in the

care of priestly academic guides.

Pop art was a reaction to this insufferable piety about art — Warhol’s soup cans and Lichtenstein’s comic strip panels were like inn signs welcoming the public back into the ordinary. Sadly, there were no inns attached to these signs — they were gestures, wonderful jokes on the art world, but behind them lay empty rooms . . . no comfort or sustenance for the weary traveler. People used posters of them as wall decorations, but went to the movies and to rock and roll for art that had a transformative power in their lives, that offered shelter from the storm.

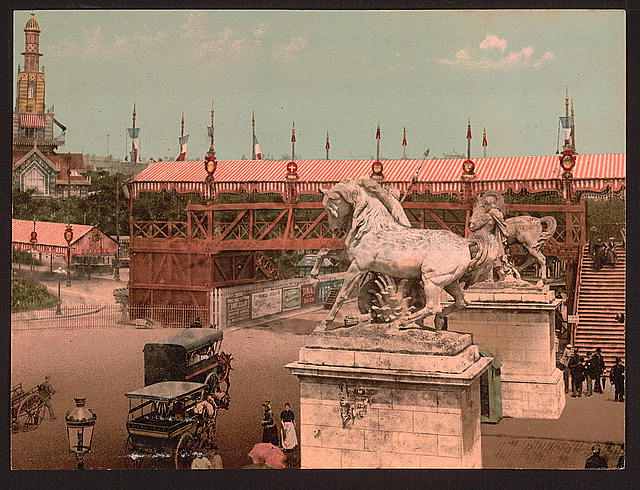

Meanwhile, officially discredited Victorian forms continued to carry, unofficially, art’s burden in the culture. Victorian melodrama, 19th-Century program music and academic painting migrated into the movies in obvious but unappreciated ways — at least by the official academic/intellectual observers of the 20th Century, who insisted on seeing film as a “modern” art, though it was modern only in its technological means. The scenic ambitions of Victorian theater and world expositions resurfaced in theme parks and in the megaresorts of Las Vegas.

Above is the interior of the Grand Palais in Paris, built for the Universal Exposition of 1900. Below is the interior of the conservatory at the Bellagio in Las Vegas, built in 1998.

At the world exposition of 1900 in Paris, there was a “Paris street”,

which offered a miniature Paris in a succession of attractions themed as

a Parisian boulevard — Loie Fuller, the famous dancer and early film

subject, had a theater in it, a popular satiric journal sponsored a

Punch and Judy show. An artificial Paris presented a sort of summary of

the real city’s spirit — a real city which lay just outside the gates

of the exhibition. This is obviously connected conceptually to the

more ambitious rendition of Paris afforded by the Paris Las Vegas, to

the Venetian, and to the Monte Carlo. It’s an example of architecture

as theater, as a vehicle of narrative.

While a self-respecting intellectual today might see the megaresorts of Las

Vegas as unique and alien examples of late 20th-Century vulgarity, a

19th-Century visitor to modern Las Vegas would feel quite at home,

culturally speaking. She would immediately recognize the megaresorts as

variants of the pavilions of the sensational world expositions of her

time. Most importantly, she would recognize the feeling of being at

home in the presence of art — an art which, like the movies and rock

music, like Fielding’s “public Ordinary”, welcomes all for their money.

Fielding’s Gentlemen of art, with their private, charitable Treats,

will come back to Las Vegas eventually, offering to stand a round of

drinks for the house . . . or maybe a few rounds of drinks. They’ve

been away a disgracefully long time, after all, and the culture has

moved on quite cheerfully without them.