From the LACMA collection.

From the LACMA collection.

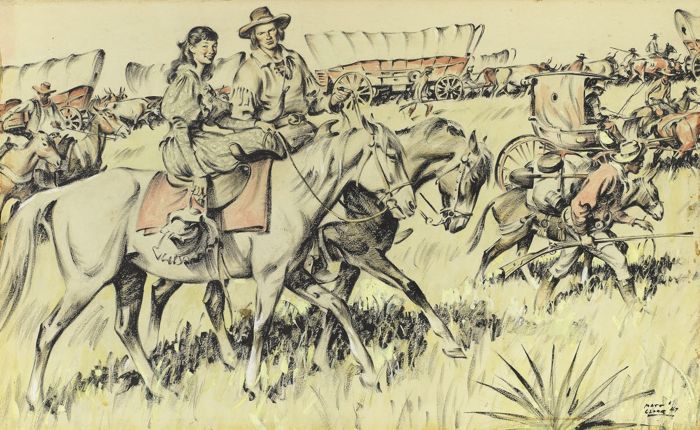

“Bonanza, The Comstock: A Caravan Returns to Gold Canyon”, American Weekly story illustration, 1947.

The Comstock Lode was the first major deposit of silver located in the United States, in 1858, in what is now Nevada but was then the western part of the Utah Territory. It created a rush similar to the California Gold Rush, leading to the founding of Virginia City — a place of fabulous wealth and vice — and the creation of the state of Nevada. The lode was pretty much played out by 1874. Virginia City has only about 1,500 residents today and makes its money mostly off of tourism, because many remnants of its former splendor are still standing, out in what is now the middle of nowhere.

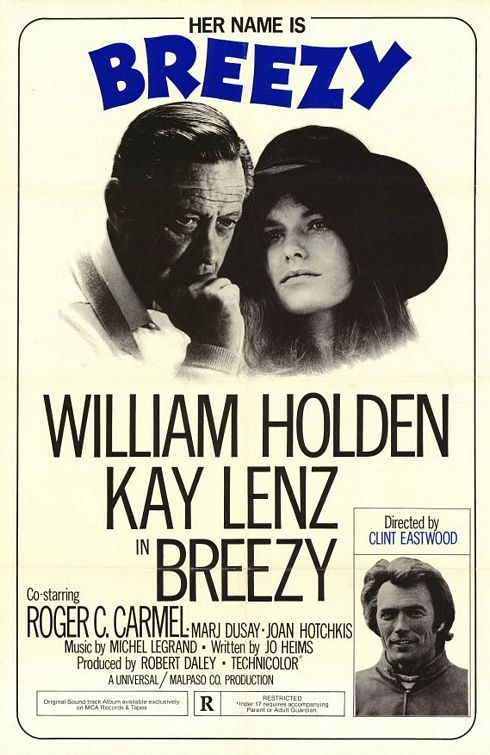

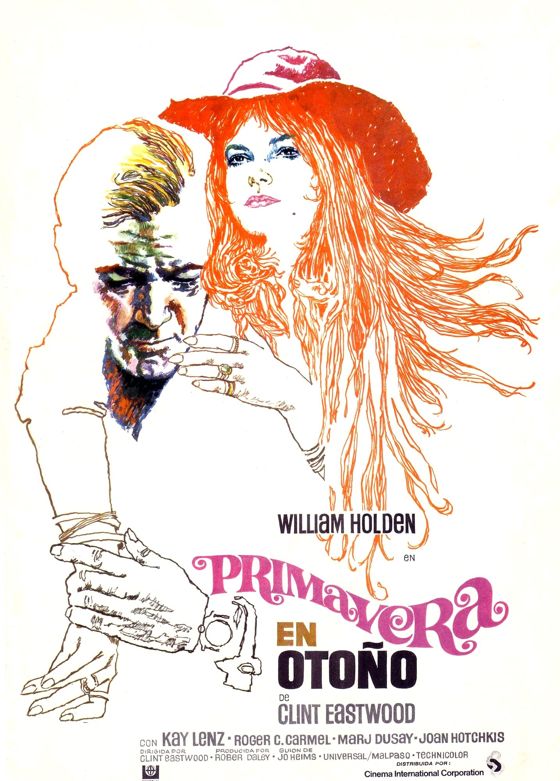

How do you portray a convincing love story between an 18 year-old woman and a 50-something man — one that isn’t totally creepy? Somehow Clint Eastwood pulled it off in Breezy, the third film he directed, in 1973.

It helps if the 50-something man is played by William Holden, still in good shape at 55, devilishly handsome and charming, and the woman is played with impeccable intelligence and poise by Kay Lenz, 20 when the film was made.

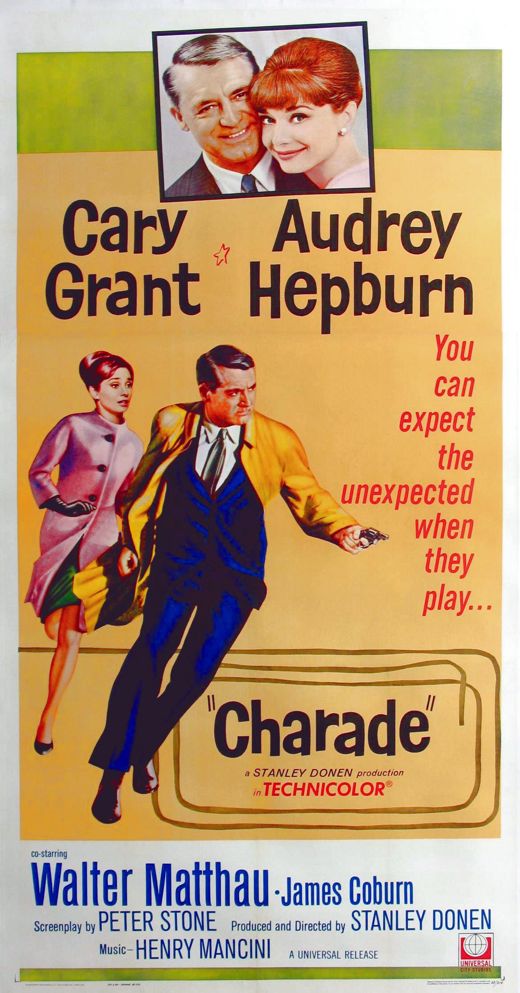

Cary Grant intuited the basic strategy when he starred, at the age of59, opposite Audrey Hepburn, 34, in the film Charade. Grant insisted that the script be rewritten, based on that casting, so that he never at any point was seen to be chasing after the Hepburn character. Every

romantic or sexual move had to be initiated by her. Grant couldn’t chase, but he could be caught, if it was clear that the woman was in charge every step of the way.

This is not how a romantic leading man normally wants to be portrayed in a love story, but in this case Grant felt it would be crucial to selling the relationship. It required Grant to substitute a delicate wit in the place of virile aggression, in deflecting her advances, and it required Hepburn to substitute a bolder kind of wit in the place of seductive elusiveness.

This is the dynamic employed in Breezy. The young woman, Breezy, is the seducer — the older man resists. It becomes a battle of wits, with high stakes — character and soul.

Breezy goes Charade one better, though, by making the young woman far more mature, emotionally, than the older man. Part of her seduction lies in exposing his puerile defenses against feeling, against emotional commitment. In the process, everything gets turned on its

head.

The woman stays in charge, but the man seduces her in return by his appreciation of and respect for her wisdom. This is closer to what is probably the typical dynamic of a love affair than most films ever get, but in Hollywood it seems to happen only when the man has the built-in power advantage of age, so that his sensitivity doesn’t unman him.

Watching a film like Breezy, where the age difference between the lovers is actually unsettling, makes you realize how cavalierly Hollywood takes the older-man/younger-woman model when the age difference isn’t so extreme. It’s normally all about the fantasies of older men, in which women are the trophies of power. As it happened, the executives at Universal, which made Breezy, didn’t like the film Eastwood delivered and dumped it without any promotion. It never found an audience — and maybe there wasn’t one. Maybe nobody wanted to see a film in which the price of some young tail was so high.

Breezy offers her older man sex up front, but she also makes him want to be worthy of her, sending him on a journey of self-discovery that is difficult and painful. She knows exactly what she’s asking, too, and she asks it because she sees something in him that he doesn’t see or has lost . . . and she trusts him to find it, trusts him to grow up.

By an unusual and improbable route, Breezy becomes a real love story — not the self-congratulatory male fantasy the Universal executives probably thought they were buying.

A perfect story illustration — something interesting is going on here, in an interesting place, and you want to know what it is.

“Surprise On the Subway”, Men's Adventure magazine illustration — stunning use of a two-color palette.

I miss New York . . .

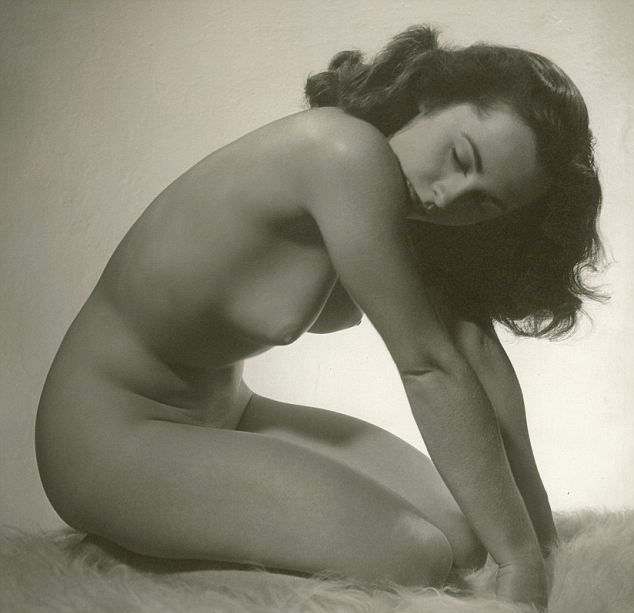

Eurasian Girl — a private, fine art painting by the great pin-up artist.

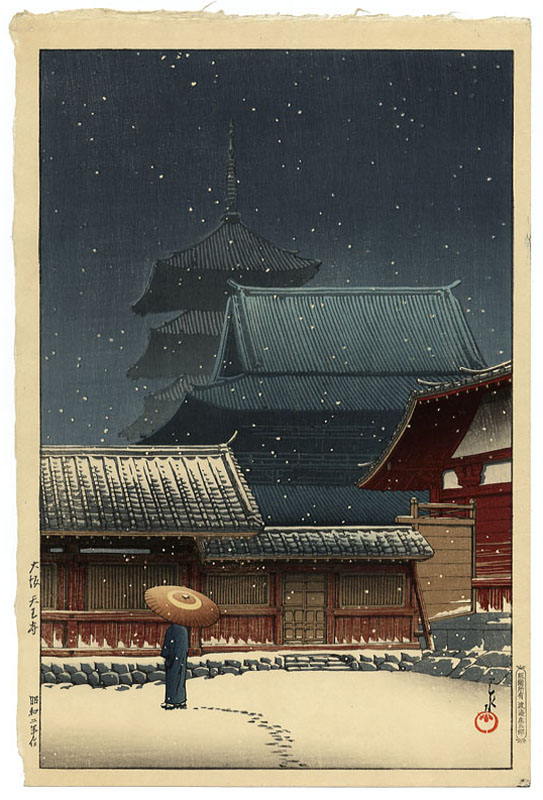

Tenno Temple In Osaka, with thanks to Brandon Taylor . . .

“A Kiss From Johnny”, story illustration, McCall's Magazine, 1952.

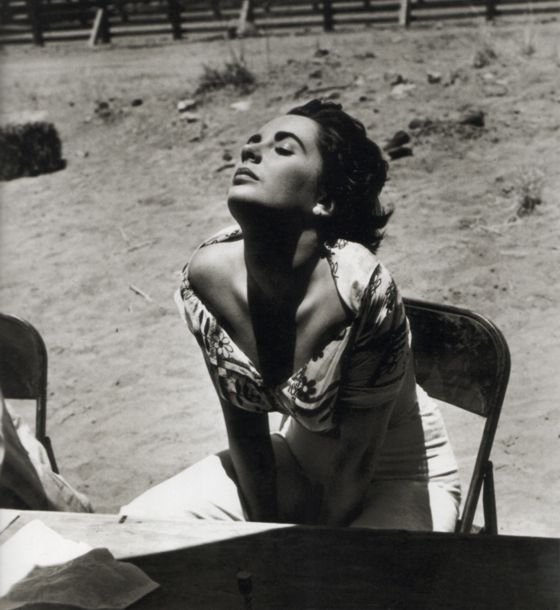

In an appreciation of Elizabeth Taylor at salon.com, on the occasion of her death, Camille Paglia had some valuable things to say about screen acting:

. . . both Ava[Gardner] and Elizabeth [Taylor] at the beginning of

their careers didn't have command of basic technical skills,

particularly dialogue. That's what people laud Meryl Streep for —

“Oh, her accents are so great; oh, her articulation is so perfect.”

But she doesn't really live in her characters, she merely costumes

them. Meryl Streep is always doing drag. But it's so superficial. It

all comes from the brain, not the heart or body. Richard Burton, who

was supposed to become the next great Shakespearean actor after

Laurence Olivier, used to say how much he had learned from Elizabeth

about how to work with the camera. Cinematic acting is extremely

understated. The slightest little flick of an eyelid says an enormous

amount, and that's where Elizabeth Taylor was far superior to Meryl

Streep. Streep is always cranking it and cranking it, working it and

working it, demanding that the audience bow down and “See what I”m

going through! See what I'm doing for you!” Streep is an intelligent,

good actress, but she doesn't come anywhere near Elizabeth Taylor on

the screen. Because she wasn't a trained stage actress like Streep,

Taylor has vocal weaknesses — at high pitch, she can get a bit

screechy — which is perfect for Martha in “Who's Afraid of Virginia

Woolf” but not so good for Cleopatra.

Vocal technique can be learned, but the kind of instinctive knowledge about how to present oneself on screen, which Taylor had, seems to be innate. If you look at early performances in bit roles by Grace Kelly, or at Audrey Hepburn's screen tests for Roman Holiday, you will note deficiencies in vocal technique which brand the actors as inexperienced in their craft, but you just don't care. They are already stars. John Ford saw it when he cast Kelly in Mogambo (below), her first important leading role in a film. William Wyler saw it when he cast Hepburn in Roman Holiday (above), her first role of any kind in a film.

Those two wily old veterans knew that what these actors had was magic, the kind that can't be acquired by any amount of training or experience.

In the studio era, new female acting prospects were put immediately into vocal training classes. The techniques they learned were simple. Young, inexperienced female actors have a tendency to speak in too high a register and don't know how to project when speaking softly, tending to swallow their words when trying to convey intimacy. Lowering the voice and developing the capacity to project an intimate tone are tricks which almost anyone can learn.

Knowing how to move in cinematic space in a way that conveys character, knowing how to project thought (or just the illusion of thought) through the eyes — these are things an actor either has or doesn't have. Vocal proficiency, as Paglia suggests, is the criterion many people use to judge acting, but it's other qualities that determine the ultimate effectiveness of a screen actor, and make actors stars.

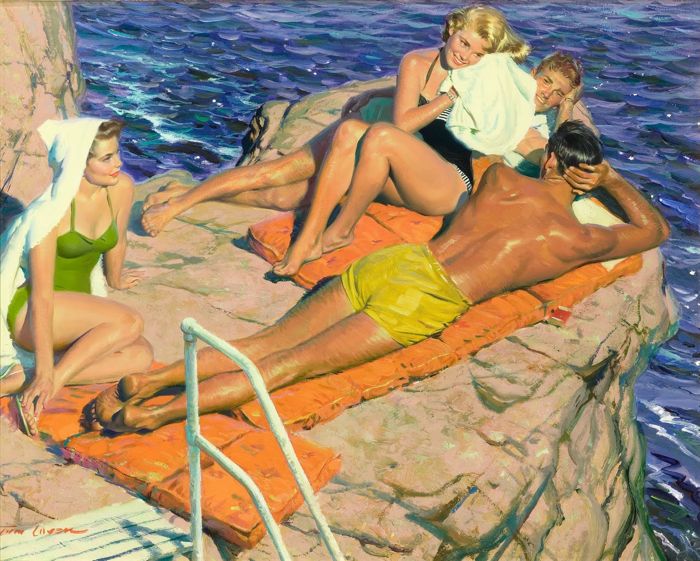

“On the Rocks”, story illustration, Good Housekeeping, 1956.

. . . to think about Lee Evans, with no clothes on.

“The nakedness of woman is the work of God.” — William Blake

[Photo © Peter Gowland]

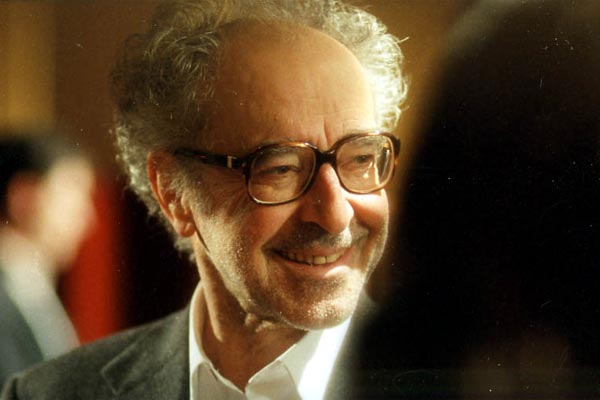

Disappointed by the box-office performance of his latest film Sucker Punch, Warner Brothers executives have quietly moved to replace Zack Snyder as the director of the new remake of Superman, which will star Amy Adams as Lois Lane. Insiders at the the studio report that a deal is close to finalization which will bring Jean-Luc Godard aboard as director of the film. Superman would be the first major Hollywood assignment for the New Wave legend, who is reported to be thrilled by the prospect.

“I have worked outside the mainstream for too long,” Godard says. “Now I am ready to cash in. My whole career in cinema has been a prelude to this. I am very excited about meeting Amy Adams and using CGI to place her in thrilling situations on screen.”