[Warning — plot spoilers below . . .]

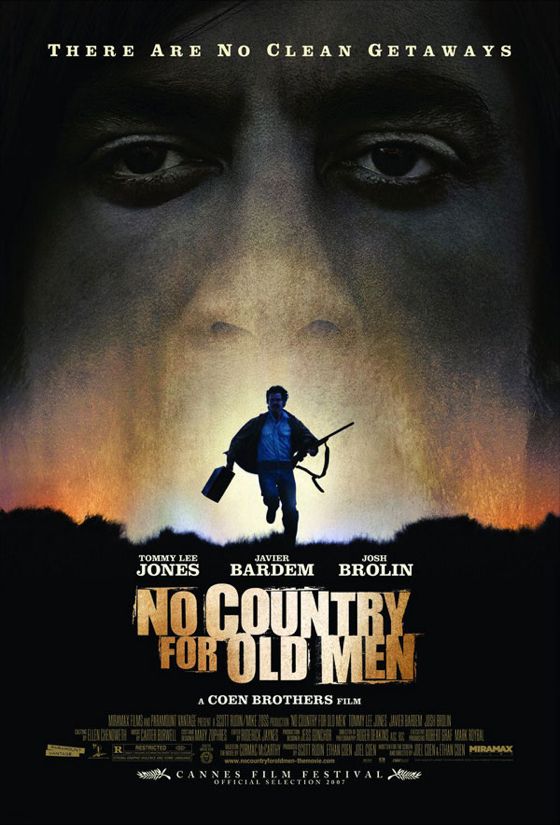

The first time I saw No Country For Old Men, in a theater when it originally came out, I found it extremely disturbing. I couldn't quite identify a coherent theme or point of view, and part of me wished I hadn't seen it, because it was so harrowing. It was much the same reaction I had the first time I saw Taxi Driver.

I suspected in both cases that I had seen a great film, an important film, and subsequent viewings have confirmed those suspicions.

The link between the films has to do with violence, of course, and the way it is presented, which is unusual. It is not in either film overly aestheticized, and it's not used as an occasion for relief from suspense or moral outrage. It is there to disturb and sicken, to create suspense rather than resolve it, to raise moral questions rather than answer them.

Many films, such as the classic Western, use violence to resolve a moral conflict, and I don't object to this, because the Western, like the fairytale, is a fable, a dream — and the violence found in both forms is read as fabulous, as it is in dreams. I do object to most modern thrillers, in which violence is used for sensation — in which a villain is demonized only to arouse our blood lust, to make us rejoice in his demise, with no deeper moral issues involved.

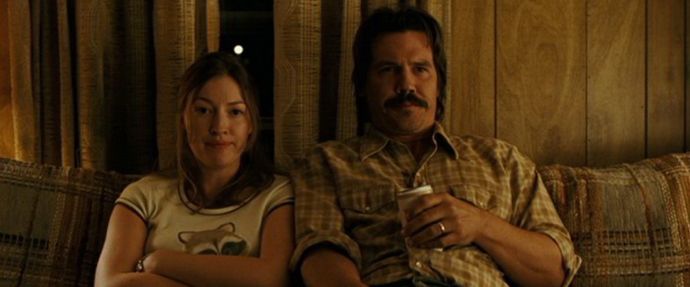

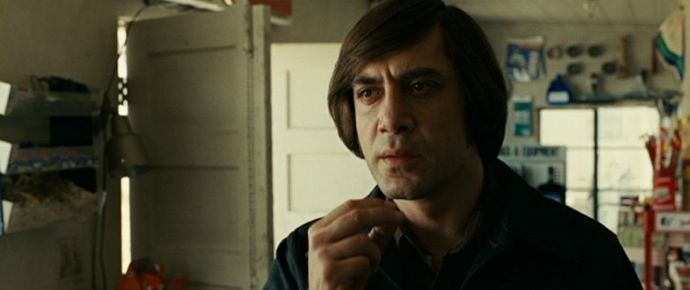

On subsequent viewings it's become clear to me that No Country For Old Men makes a very deliberate and calculated break from the usual formula of a modern thriller, violating convention in a shocking way, and that this is the key to its meaning. In the first two-thirds of the film, the story sets up a duel between a vicious psychopathic killer and a sort of anti-hero, likable but morally compromised. Hovering in the wings is a moral presence, in the form of a thoroughly good local sheriff, who is not directly involved in the duel.

Then, without warning, at the beginning of the third act, the anti-hero is killed, and the decent man takes his place as the film's protagonist. He never engages the psychopath — doesn't outwit or outfight him, doesn't bring him to justice. He simply stands against him as a kind of witness.

Things get almost mystical towards the end. It seems as if the mere presence of goodness can make the killer vanish into thin air — as if the fact of goodness diminishes him, makes him vulnerable, saps his power. He “gets away” but seems to have lost his existential substance.

The universe of the film is very bleak, its violence incomprehensible and thus utterly terrifying. We are not told that countervailing violence on the side of justice can defeat it, only that moral rectitude can stand in the way of such violence becoming the definition of human existence. The film's denouement is purely spiritual, not practical.

It's not much, I guess, but it's so much more than the lies about violence told in most movies today, which do not prepare us for the world as it actually is and thus do not offer us any authentically hopeful or honorable way to live in it.

the ending of the book is rather more interesting

Haven't read it but can see that I must.