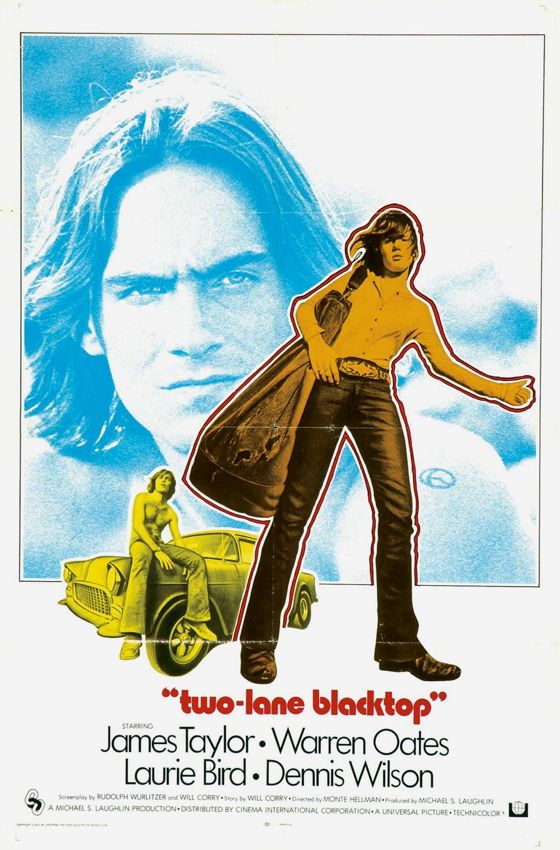

If John Ford had ever made a rock and roll road picture, it would probably have looked a lot like Monte Hellman's Two-Lane Blacktop, from 1971 — which is a crude way of trying to evoke Hellman's unique blend of formal mastery and eccentric invention.

Hellman was one of the directors who re-invented American movies in the Sixties, applying a deep understanding of film history and film technique to new subjects and attitudes. Unlike a number of the other rebels of his generation, Hellman never became a mainstream commercial director. His highest profile film, Two-Lane Blacktop, became an instant cult classic and remains one to this day, considered one of the seminal works of Seventies cinema, but the studio distributing it refused to promote it and it did not make money.

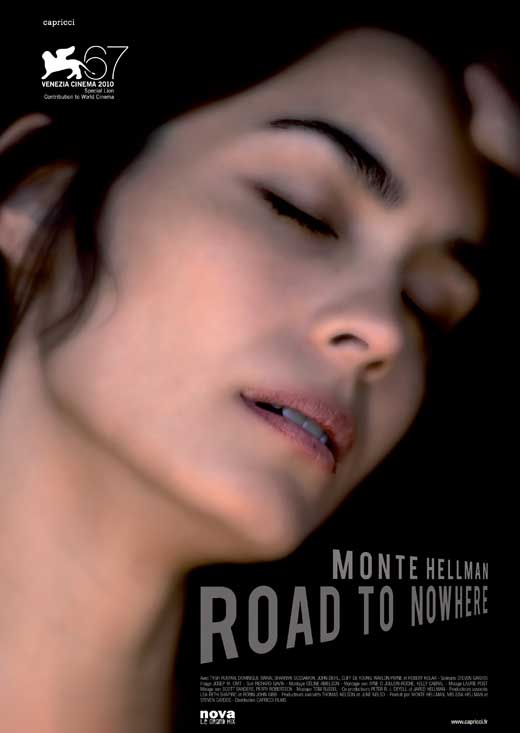

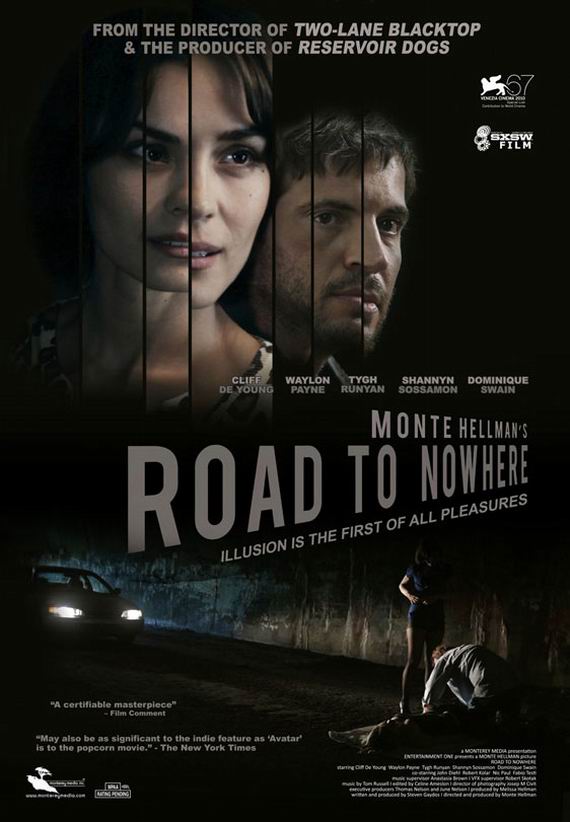

Hellman has made a number of highly-regarded independent features since then, but there was a twenty year gap between the last of them and his new feature Road To Nowhere, which was released in 2010 on the festival circuit and has been hailed as Hellman's return to the height of his powers. It has been theatrically released in France and is about to get a limited theatrical release in the U. S.

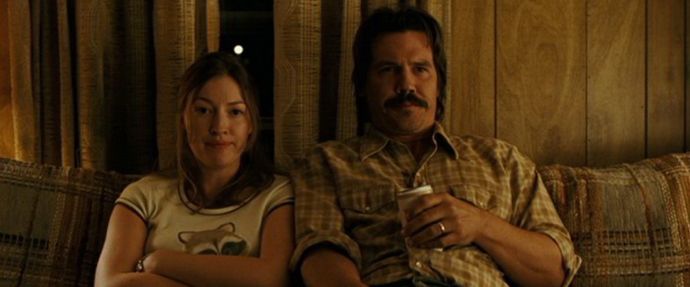

It's an extraordinary film — the first feature shot on the Canon 5D, essentially a still camera with breathtaking HD video capabilities, in locations all over the world, but mostly in North Carolina, and starring the stunning Shannyn Sossamon, who here achieves the status of an authentic screen goddess.

It's a film about filmmaking, in which a real-life crime infects a movie being made about that crime. The tale becomes a hall of mirrors, a complex intellectual puzzle that nevertheless delivers a shocking visceral jolt at the climax. You won't, however, walk away from the film dwelling on its devious structural intricacies. What you will remember instead, I suspect, is a film that delights and amazes from shot to shot, sequence to sequence, with the pure joy of making images, pictures that move, spaces that seduce you into emotional involvement with characters and situations with or without your conscious consent.

I think you will feel privileged to have spent a couple of hours with a cinematic master, someone who reminds us that it's still possible to make real cinema today. This is a proposition that can only be argued on screens in darkened theaters, by an advocate who is both passionate and supremely skillful — by an artist like Monte Hellman.