The structure of the Coen brothers' film Fargo is very odd. It starts with a half hour of what is essentially set-up for the tale we'll be watching, and only then introduces the film's protagonist, Marge Gunderson.

This would not make sense if Fargo were merely a crime thriller, as it seems on the surface to be. Instead, like so many of the late works by the Coen brothers, Fargo is essentially a meditation on goodness, on the mysterious presence of goodness in a thoroughly fucked-up world.

The first half hour of the film immerses us in that fucked-up world, so deeply that we think it's going to be the world of the film. This is not troubling, because the treatment of the fucked-up world is so funny, in a dark way, so well observed and so intriguing. We watch as a handful of stupid, immoral louts maneuver themselves into darker and darker realms of disaster, and it's fascinating the way watching a slow-motion train wreck would be fascinating. The lively filmmaking, the brilliant performances, the permission we're given to laugh at the louts — all these things promise a grand entertainment.

And then, suddenly, everything changes — because we are introduced to Marge and her husband, good, decent people in a good, decent marriage. Marge is pregnant. She's also the police chief of the town where the disasters brewing in the first part of the film come to a head in a ghastly way. She's the guardian who has to take the early morning call when things go wrong, in a way that could threaten her community.

She's the one who has to go out in the freezing cold on a lonely stretch of highway to examine three grisly corpses, while dealing with morning sickness. And she doesn't complain. She is cheerful, kind to everyone she meets, but tough, and in her own deadpan way smart as a whip. She's the best of what ordinary Americans can be, the best of what ordinary human beings can be. It's enough to make you cry.

It's enough also to change a crime thriller into a spiritual parable — because now we know that Marge will have the task of tracking down the louts we've already met, entering their world of moral nullity and bringing them to justice . . . or not. The stakes become impossibly high, and sublime. And none of it plays as pious or preachy, because Marge's goodness is funny — we are given permission to chuckle at her relentless decency, the ferocious wit she displays in exercising that decency in situations where decency seems to have no place.

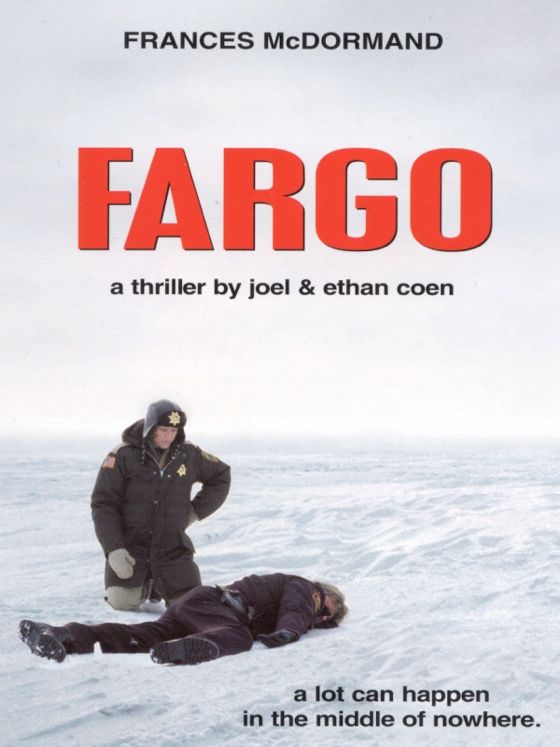

On paper, it must have seemed like an impossible and thankless role, but it was written for Frances McDormand, and the brothers clearly knew what she would do with it — convey intense intelligence in the simplest of ways, skirt the edge of caricature with fine calculation, and be adorable doing it. Adorable and quite often sexy. A pregnant small-town police chief who's sexy.

It's a truly brilliant performance, in a film that is truly brilliant — brilliant on terms of its own devising, that no other filmmakers working today could have pulled off, or even imagined.

Hollywood used to know how to make virtue glamorous — see Casablanca, for example — but the Coen brothers here make it quirky, implacable and utterly irresistible.