. . . loves to entertain family and friends with her exquisite water ballets, performed in her pool. Here she demonstrates her famous “swan pose”, which never fails to bring a gasp from onlookers.

. . . loves to entertain family and friends with her exquisite water ballets, performed in her pool. Here she demonstrates her famous “swan pose”, which never fails to bring a gasp from onlookers.

. . . looking stylish on the patio of my sister Anna's house in North Carolina.

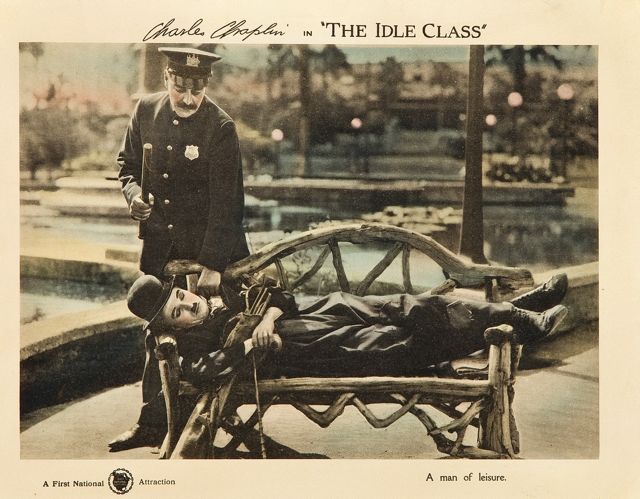

Curiously, it was cinema, a supposedly new art form, that remained, along with jazz perhaps, the most self-confident of arts in the 20th Century, never for a moment doubting its task, which was traditional, conservative even, humane and popular, unlike the older “high art” forms which became the province of ever-dwindling cultural elites.

Hiding behind the mask of its purely technological novelty, it carried on the art projects of the 19th Century without shame — Victorian academic painting, Victorian theater (especially Victorian spectacle-theater), program music and the variety stage.

This has to be one of the most astonishing sleight-of-hand acts in the whole history of art.

Baumhofer was an American illustrator with good, solid draftsmanship and a knack for creating thrilling spatial effects, even for scenes not quite as spectacular as this one . . .

My friend Juniper was in town from the Bay Area this weekend. On Saturday she attended a wedding, today we ran around in search of further adventures.

She found some shade in Red Rock Canyon, above. Below, she ate Bananas Foster at Mon Ami Gabi — high adventure, indeed.

She pocketed $10 playing roulette at the El Cortez Casino . . .

. . . and left town a winner. Yes!

My nephew Harry and my friend PZ discussing movies — the subject here, Kurosawa!

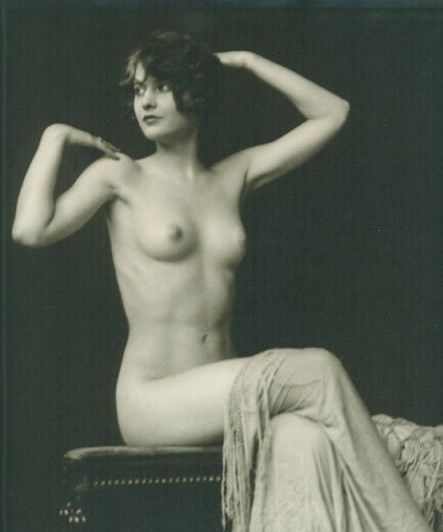

The former Miss Ruby Stevens, in excelsis . . .

My mom and my friend Mary Zahl discussing smocking in the living room of my sister's house in Hampstead, North Carolina.

Just as the industrial labor process separates off from handicraft, so the form of communication corresponding to this process — information — separates off from the form of communication corresponding to the artisanal process of labor, which is storytelling. This connection must be kept in mind if one is to form an idea of the explosive force contained within information. This force is liberated in sensation. With the sensation, whatever resembles wisdom, oral tradition or the epic side of truth is razed the ground.

— Walter Benjamin, The Arcades Project

Storytelling is linked to artisanal labor because it is created out of the life experience of an individual storyteller, most especially the time spent learning the craft of it. It's not so different from making furniture by hand. Information, by contrast, is merely collected and repackaged. It has the nature of an industrial product, which can be separated from the process of its creation and sold like any other commodity.

Storytelling embodies, at its best, as Benjamin notes, wisdom, tradition and a truth that transcends both the moment and the immediate context of its telling — it is epic in that sense. Information has commercial value to the degree that it embodies sensation — sensation in the sense of surprise or shock value, and sensation in the sense of newness or exclusivity.

Most modern movies don't tell stories — they sell sensation.

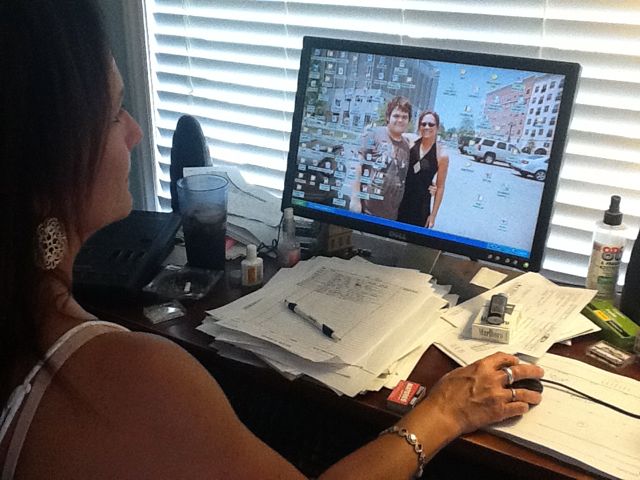

My sister Roe in her home office in North Carolina, with a picture of herself and her son Max on the computer.

When she was a little girl I used to call her Roetina, and I still do — I don't know why.

As you can see, she is a smoker and allows smoking in her home. Yes!

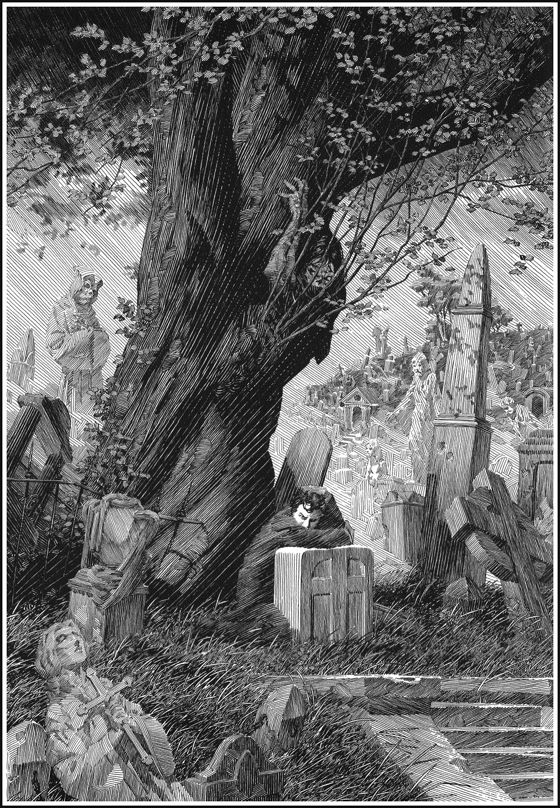

Illustration, Frankenstein, 1983

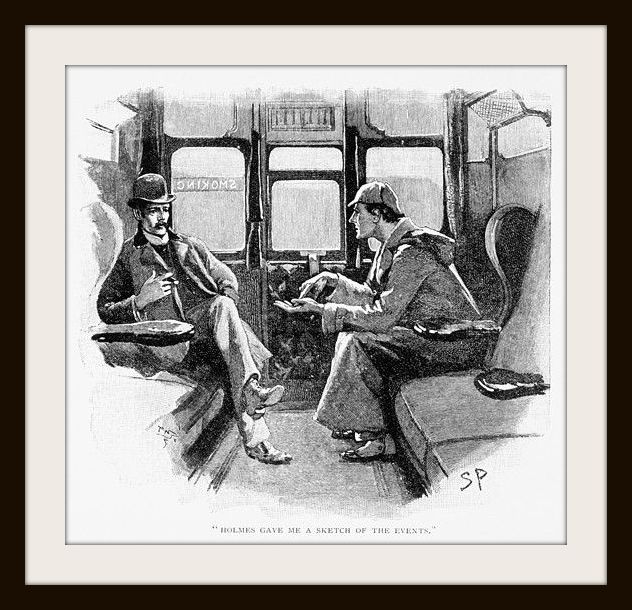

We don't really have

Fall in the Mojave Desert, but when the killing heat of the summer

subsides, the change creates an autumnal feeling. Fall doesn't

officially begin anywhere until 23 September, but September is an

autumnal month, and it's Autumn now in my mind, which I'm celebrating

by re-reading Sherlock Holmes stories.

What I like about

these stories is something that's hard to translate into a dramatic

medium like movies — the sense of calm and order, which no sensational

misdeed can ever really disturb. Holmes continues on his unemotional

but relentless battle against crime, Watson continues on his course of

adamantine loyalty. The crimes intrude only to remind us that the

wickedness of this world can't vanquish an everyday dedication to

decency, and that friendship is more thrilling than scandal.

. . . barbecue in Wilmington, North Carolina. They cater.

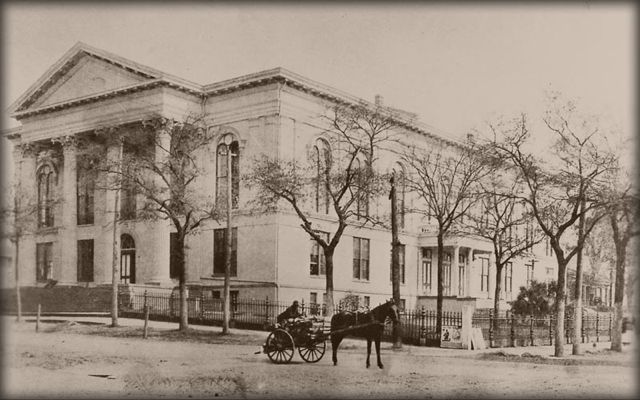

Thalian Hall in Wilmington, North Carolina, my home town, was completed in 1858, using a combination of slave and free black labor. It has a large theater, a grand ballroom and a number of other facilities that have been devoted to various civic activities over the years. Now wonderfully restored, it remains in use as an arts center and town government office building.

After the unfortunate incident which closed his Washington theater (above) in 1865, John T. Ford managed Thalian Hall for a while.

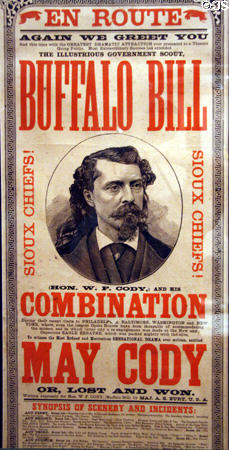

Before he created his great arena show, Buffalo Bill Cody appeared there in a Western play, May Cody or, Lost and Won, based loosely on his life, which concluded with a display of his prowess as a marksman.

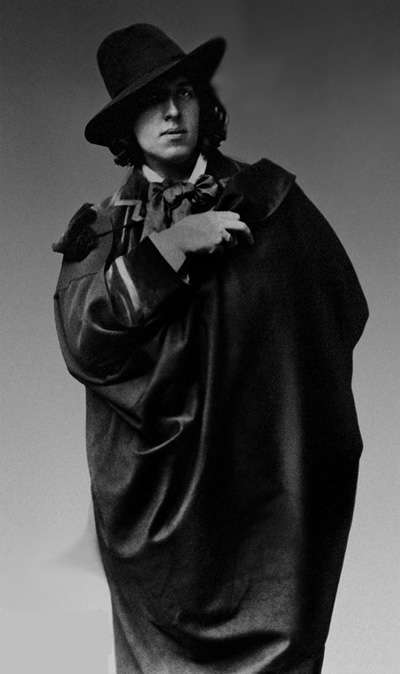

Oscar Wilde gave a lecture there, to a mostly full house. His “exquisitely beautiful” language was noted in the local newspaper.

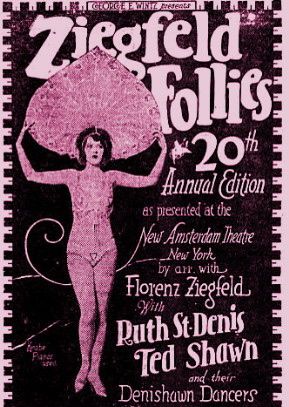

Wilmington's location as the hub of several rail lines made it a town frequently visited by touring theatrical companies, including a road company of The Ziegfeld Follies in 1928, which played at Thalian Hall.

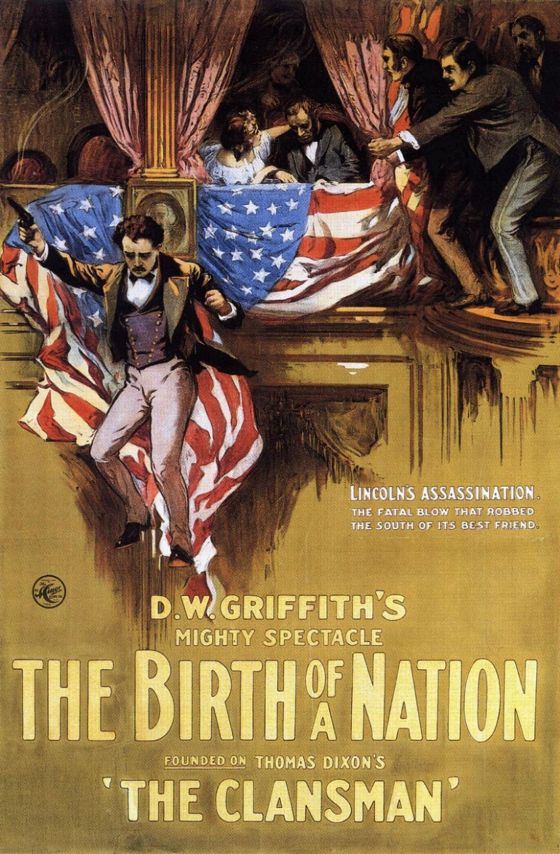

Although rarely used as a motion picture theater in its heyday, the Wilmington premiere of The Birth Of A Nation took place at Thalian Hall in 1916. That film was often booked in legit houses. In the days of segregation, attractions at Thalian Hall played mostly to white audiences, though there were always small sections of the house reserved for blacks. When attractions of special interest to blacks were booked, most of the house would be reserved for them, with small sections set apart for whites.

Today, Thalian Hall has an art film program, and I saw The Tree Of Life there this summer. The management felt the need of posting a disclaimer in the lobby (above), warning patrons that the film was unusual. There had apparently been complaints at showings earlier in the week. The film had been scheduled to play in a regular commercial multiplex in Wilmington, but its poor opening at other theaters caused the multiplex to replace it with a different film. Thalian Hall took up the slack.

Thalian Hall is usually thought to be haunted, as well it might be, having hosted so much of the forgotten history of American show business — a grand mixture of highbrow and lowbrow entertainment, though for much of Thalian Hall's existence such distinctions were not made. It was a palace dedicated to all sorts of dreams.

Thalia, incidentally, was one of the nine muses — the patron of comedy. (The wardrobe malfunction in the portrait of her above, by Jean-Marc Nattier, 18th Century, is a reminder that everybody needs to lighten up about certain things from time to time.) The muses were the daughters of Mnemosyne, the goddess of memory, all fathered by Zeus on nine successive nights — so it's fitting that Thalian Hall has become a house of memories as well as dreams.

Facebook friend Ray Sawhill has a theory that classic Westerns deal with the themes of shame and honor, which began to feel old-hat in the Sixties when movies shifted more and more to the paradigm of guilt and therapy, following trends in the culture at large.

This wasn’t a universal trend, however — even though it came

to dominate Hollywood (which still has a strong culture of guilt and

therapy) as well as various other self-styled cultural elites — because

whenever a Western dealing with the themes of shame and honor has

managed to slip past the Hollywood gatekeepers, it has invariably found

a big audience. See Unforgiven and the new True Grit, for example.

As I see it, the difference between shame and guilt in this context would be — shame is something you feel because of your own failings, while guilt can be seen as something imposed on you unfairly by others. The difference between honor and therapy would be — honor requires you to make moral choices and take moral actions, while therapy can be seen as something you pay for with cash and consume passively, without the intervention of moral thought.

Therapy strives for vindication and healing — honor strives for redemption, and redemption is the theme of almost every great Western.

You have to have unusual power and authority in Hollywood to get a shame-and-honor Western made, you have to be Clint Eastwood or the Coen brothers, because the industry simply doesn’t understand such movies, and to the degree that it does understand them, it hates them, even when they make a lot of money — perhaps especially when they make a lot of money. If there ever is a full-scale revival of the traditional Western, it will have to originate outside of Hollywood.