Although the first truly important narrative film made in America, The Great Train Robbery from 1903, was a Western of sorts, it took about five years before the Western-themed film resolved itself into a recognizable genre. It was a wild and wooly ride, which the form almost didn't survive. Like The Great Train Robbery, early Westerns focused on violent crimes. They modeled themselves on sensational Western dime novels and appealed mostly to kids and male working-class moviegoers — and to foreign audiences. When producers and distributors decided to court a higher class of clientele, including women, the Western came to seem unsavory, driving the better sort of folk away from the fancy new movie palaces that were gradually supplanting the storefront nickelodeon.

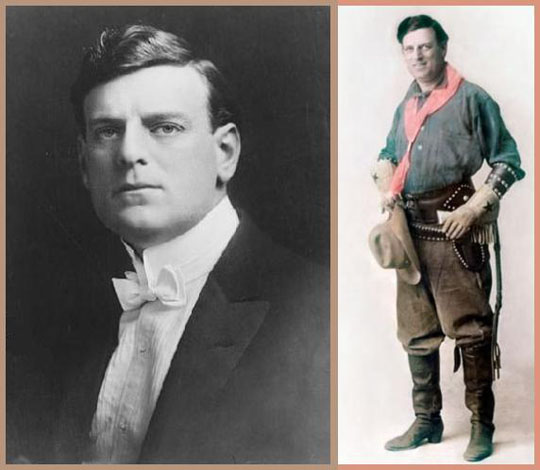

Gilbert “Bronco Billy” Anderson (above), who had played three bit parts in The Great Train Robbery, rode to the rescue by creating a Western hero who appealed to all classes and to women. “Bronco Billy” might start off as a bad man but his heart was always in the right place and he always ended up tamed by and defending conservative social values, usually personified by a beautiful and virtuous woman.

When Anderson lost interest in Westerns, and movies in general — his dream was to become a theatrical impresario — William S. Hart (above) was there to fill his boots. Hart played a tougher and more taciturn Western hero but like Anderson always came around to the defense of traditional values, religion and social order.

In the 1920s, an era of industry consolidation, the studios generally gave up on Westerns that might appeal to everyone. The B-Western was born, marketed once again to kids, to working-class males and to foreign audiences. These constituted a reliable though limited base for Westerns, which had to be cheap and formulaic to make money — but they made a lot of money on that basis and were a major source of studio profits. They produced big stars like Tom Mix, above, but stayed lean and mean where budgets were concerned.

The wonderful book by Andrew Brodie Smith pictured at the head of this post tells the tale of how the Western was born and how it evolved into a genre — restricted in form by the 1920s but still vital and immensely valuable to the industry. Well-researched and written, it's essential to understanding the role and nature of Westerns in the earliest years of cinema.