Howard Hawks might seem the least logical choice to direct a 50s musical. The Freed unit at MGM was setting the standard then, and Vincente Minnelli was setting the standard for the Freed unit, with his baroque visual style, lush and mannered. His mobile camera and long takes made the camera itself a performer in the show, a sort of contrapuntal melody line that worked in concert with the music and the dance choreography. Even Freed directors who lacked Minnelli's visual inventiveness tried to approximate it, at least in the musical numbers. Hawks, by contrast, had mastered a no-nonsense visual style that never called attention to itself. The impeccable craftsmanship of this style had an elegance and virtuosity that equaled Minnelli's, if you did pay attention to it, but Hawks worked hard to make sure that no one would. He wanted it to serve the story unobtrusively, so you never quite knew why his movies were so appealing and effective.

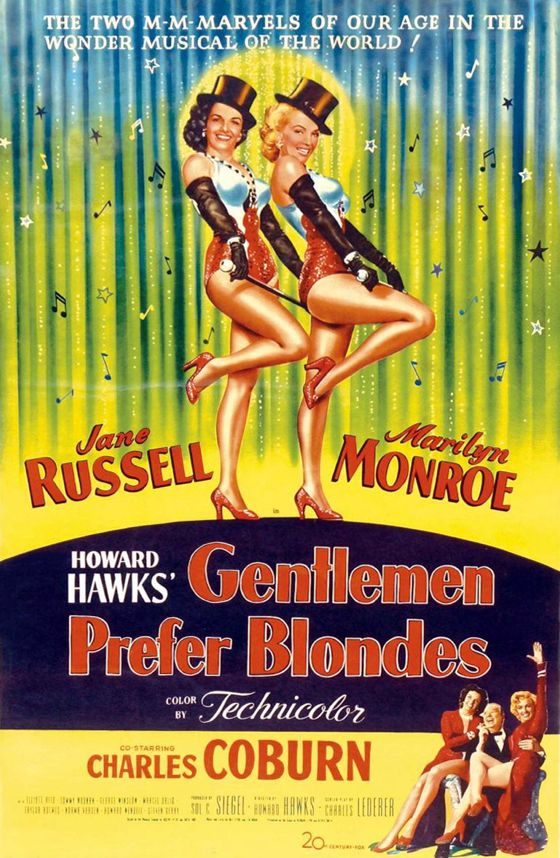

Miraculously, the Hawks style worked perfectly in one of the best of all 50s musicals, Gentlemen Prefer Blondes. The film was tricked out in bold Technicolor, which provided the surface glamor people expected in a musical, and helped disguise the simplicity of the camera work. In the musical numbers, impeccable shot sequences covered the performances expertly, with brilliantly timed cuts that kept up the momentum Minnelli and the other Freed directors achieved through long takes.

This was an advantage to Hawks because his stars, Marilyn Monroe and Jane Russell, were not virtuoso musical comedy performers, trained in vaudeville or on the Broadway stage, as so many of the MGM musical comedy stars had been. Short takes allowed Monroe and Russell to achieve perfection in brief segments, even as Hawks's shot sequences gave the impression of a complete and coherent performance experience. Yet you never sense, as you do in modern music videos or musicals, with their nervous, nearly hysterical cutting, that the editing is meant to distract you from the limitations of the performers. The editing of the musical numbers in Hawks's film has a stately rhythm and assurance that make it seem inevitable and seamless.

The film as a whole has this same feel of seamless momentum — the gags are delivered clearly and fast and then replaced by new ones. They sparkle and amuse all the more for not overstaying their welcome. Indeed, it's clear that Hawks wasn't trying to make a musical at all — he was trying to make a comedy with musical numbers in it, and he made sure that the musical numbers concentrated on wit and humor, to keep the tone of the whole film consistent.

In the end, this strategy is every bit as exhilarating as the expressionistic bravura of a Minnelli or a Berkeley. It's hard, however, to think of any other director besides Hawks who could have pulled it off, which makes Gentlemen Prefer Blondes a most singular achievement in the history of Hollywood musicals.