Click on the image to enlarge.

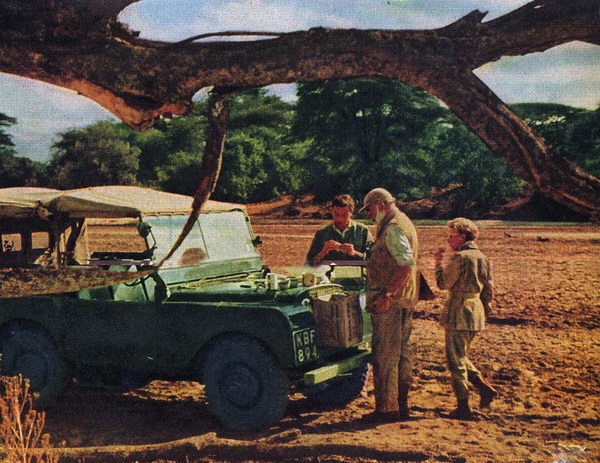

The last of the books Hemingway left unpublished (and unfinished) at his death was a more or less factual recounting of parts of his 1953-54 safari in Africa with his fourth wife Mary. It resembled in its intent his more or less factual account of his first African safari in 1933, Green Hills Of Africa. Both were attempts to make a non-fiction record, shaped with a novelist’s skill, of an experience that was very important to him.

About half the manuscript of the later book was published in 1999 as True At First Light, edited and abridged by Hemingway’s son Patrick, who tried to emphasize the dramatic highlights of the safari and to preserve the best passages of writing in the book. It’s an uneven work — with some passages of writing that are very fine, indeed, and some that are dramatic, but which are all set down amidst more ordinary reportage of the safari’s daily life and routine.

Six years later two scholars published the whole manuscript, with minimal editing, as Under Kilimanjaro. Although the ordinary reportage is more abundant and extended, it creates a smoother read. This leisurely recounting of the safari was what Hemingway apparently wanted the book to be — a long, almost conversational address to the reader, giving her the day by day events as Hemingway saw them.

There’s almost a glass by glass, bottle by bottle catalogue of what Hemingway drank. There are accounts of hunts that were successful and of hunts that were unsuccessful, of excitement and boredom. Hemingway treats us to his peculiar brand of humor and badinage, which rarely come across as funny or witty (at least to this reader) but which seem to have delighted him. He charts the ups and down of his and his wife’s relations, the tensions and the pleasures of their marriage. He finds ways of boasting of his prowess as a hunter by setting them amidst self-deprecating remarks about his inadequacies. He ventures into intimate family territory, saying unkind things about his brother Leicester’s book, for example. He pontificates about the work of other writers, dealing out praise and criticism with lofty assurance.

It is in some sense a lazy book, almost a stream-of-consciousness journal of his thinking which he hasn’t bothered to shape into something more acute and universal. But that, oddly, is its charm. Reading the book is like hanging out with the everyday Hemingway — Hemingway engaging in a tune-up bout with his craft, rather than a title fight, with his championship belt on the line. If you don’t love Hemingway and his work, you will probably find most of the book tedious and flat. If you do love Hemingway and his work, you will find it endearing — an honest and generous sharing of himself by a genius who’s not firing on all cylinders but still takes his profession in deadly earnest.

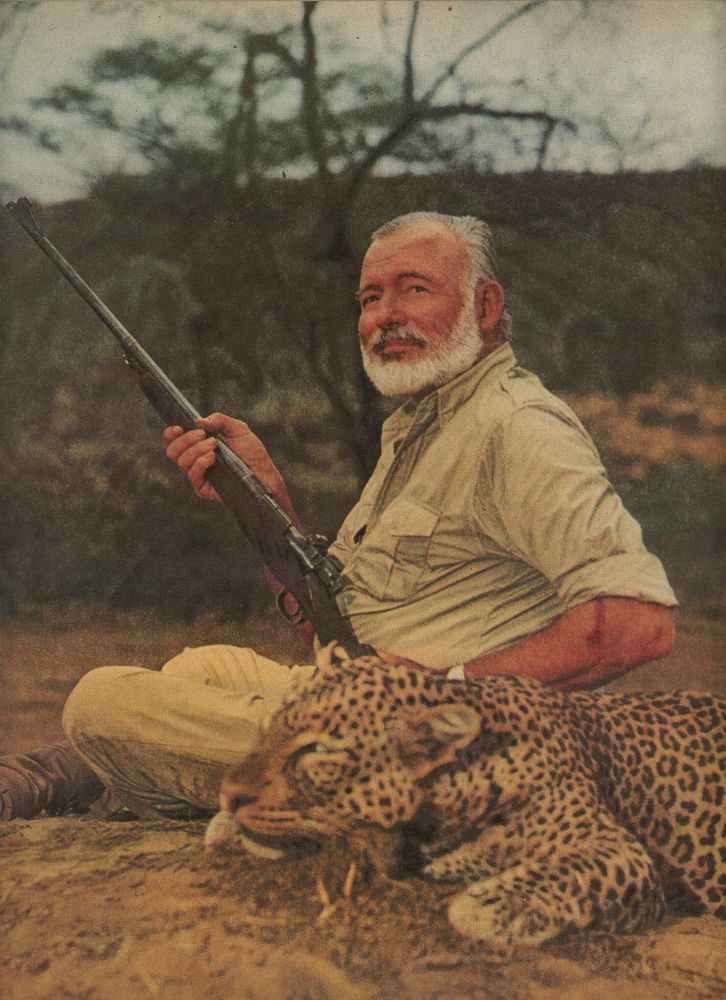

It’s interesting to note how Hemingway’s feelings about hunting had changed in the time between the two safaris. He still loved hunting but no longer killed for trophies. On the second safari he was acting as a semi-official game warden. He shot animals to supply his camp and its attendants with food, and shot predator cats, lion and leopard, only if they had been taking livestock from local villages and were thus marked for elimination by the game department. He had lost heart for killing as a sport only.