Something even Hieronymous Bosch could not have imagined — an ambulatory human rectum that speaks. Lo, the end of days is at hand . . .

Monthly Archives: September 2012

EARLY ROMAN KING

EARLY ROMAN KING

EARLY ROMAN KING

EARLY ROMAN KING

WHAT I’M SPINNING NOW

AN AUGUSTUS SAINT-GAUDENS STATUE FOR TODAY

TEMPEST TRACK BY TRACK

Below are links to my commentaries on all the tracks on Bob Dylan’s album Tempest. They don’t pretend to offer comprehensive analyses, just my responses to some very complex and resonant songs.

Tempest is a magisterial work — a sweeping, disquieting, profound survey of our world and times. There has never been anything quite like it in American art, and there may never be anything quite like it again. As far as I’m concerned it takes its place with Moby Dick and Leaves Of Grass and Huckleberry Finn as a classic work in the national canon.

Click on the titles of the songs for the commentaries.

A JEAN-GABRIEL DOMERGUE FOR TODAY

TEMPEST TRACK BY TRACK — ROLL ON, JOHN

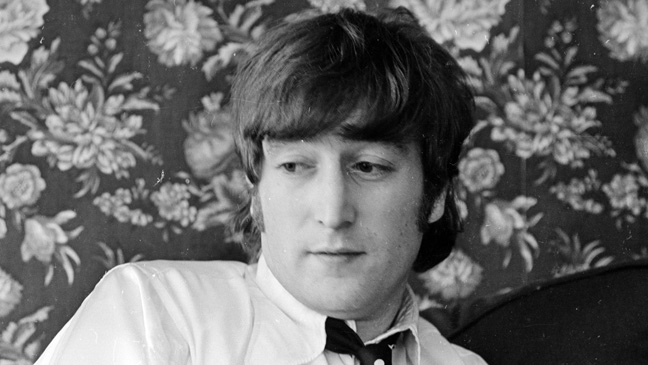

Bob Dylan and John Lennon came into my life within months of each other in the Fall of 1963, when I was 13 years-old. They changed my life, of course — they changed everything, and I watched that change play out in front of my eyes for the rest of the Sixties.

Lennon was shot and killed by a lunatic in 1980 — it was one of the great cultural tragedies of the 20th Century. He has been endlessly mourned, and yet . . . I have never really believed in his death. The music he made with The Beatles, and afterwards, is so immediately joyful, has remained so alive in the culture, that it seems as though he never left this world.

But he did leave this world, and 32 years after he left it, Bob Dylan has written an elegy for him, a eulogy, a lament — a song called “Roll On, John”, which ends Dylan’s album Tempest. Tempest is a work of art suffused with a sense of loss and tragedy and horror — and hope and defiance and faith, though it pulls no punches. It admits of no consolations except those that can be received in the ghastly, immediate presence of mortality and sorrow and evil.

Lennon rolls on in Dylan’s song, but not in “music that will never die” or “inspiration that will never die”. He rolls on in death, beyond death, beyond a grave. Dylan asks us to cover him over and let him sleep. To Lennon he says, “Shine your light, move it on” — move it on past this earthly life.

It’s the sweetness of the melody of this song, and the heartbreaking tenderness of Dylan’s vocal, that distinguishes “Roll On, John” from just another tribute, just another celebration of a lost prince. Dylan seems to be singing this in the presence of Lennon’s corpse.

Dylan does the best singing of his life on Tempest. His voice is ravaged now, its power and sweetness are gone — he has nothing to rely on but art, subtlety, the slightest inflections of rhythm and breath. You can learn all you need to know about what singing’s really all about from listening to this album.

It wasn’t until I heard “Roll On, John” that I truly realized that John Lennon was dead — dead, dead, dead — and that the part of him that rolls on is not memory or echo or anything that can be recorded and packaged. It is light, supernatural light, glimmering very faintly amidst the ruins of a shameful and profane and horrifying world.

Back to the Tempest track list page.

TEMPEST TRACK BY TRACK — TEMPEST

In the chaos and horror of the sinking of the Titanic, there is a watchman aboard. He’s asleep — dreaming of the disaster befalling him and those he’s charged with watching. “The watchman he lay sleeping, the damage had been done — he dreamed the Titanic was sinking, he tried to tell someone.”

This figure is Dylan, I think — Dylan the prophet. He sees what’s happening to himself and his country and his world, but his vision is like a dream, and that’s all he can testify to. “I had this dream,” he says. “Maybe it’s important — maybe it means something.”

You decide.

Cameron’s film Titanic is one of the most important works of art of our lifetimes. It looms as large in the culture now as the actual sinking of the actual Titanic. Dylan’s song is as much about this film as it is about the real ship that sank. The song is a conversation with the film.

It was a conversation Cameron started, putting lines from Dylan songs into the mouth of Jack, the film’s protagonist. “When you got nothing, you got nothing to lose,” Jack says in the poker game in which he wins his passage on the ship. “I’m just a tumbleweed, blowin’ in the wind,” he says to Rose.

People criticized Cameron for this, calling the lines anachronistic — though of course the lines were as old as the hills when Dylan used them. Now, in Dylan’s account of the sinking of the Titanic, he references Cameron’s film repeatedly.

He creates his own climax, however, but it is in many ways the same as Cameron’s climax, in which death and loss are redeemed by sacrifice. Jim Dandy in Dylan’s narrative smiles ruefully when he realizes that the ship is sinking, because he doesn’t know how to swim. He has a place in a lifeboat but he gives it to a crippled child — and then when death has its triumph, Jim Dandy’s heart is at peace, untouched by the horror. He has defeated death by sacrifice, just as Jack does in the film.

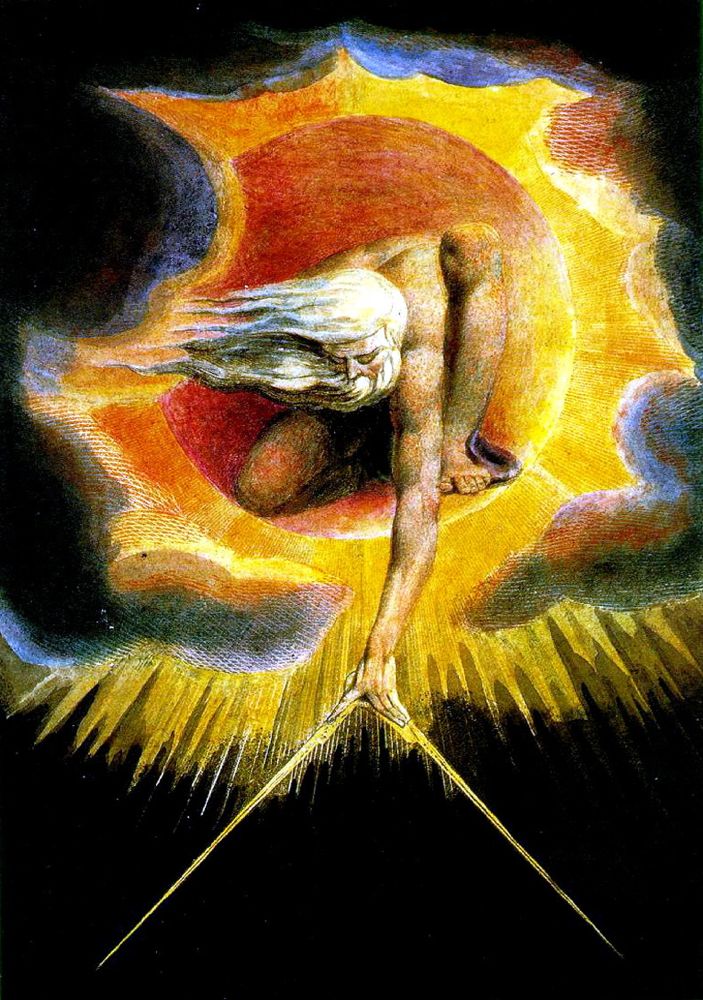

What’s left is meditation on the apocalypse — and Dylan gives that to the ship’s captain, facing his end kneeling before the wheel:

In the dark illumination

He remembered bygone years,

Read The Book Of Revelation

And filled his cup with tears.

You will remember that the priest in Cameron’s film quotes from Revelation when the ship goes down:

And I saw a new heaven and a new earth: for the first heaven and the first earth were passed away; and there was no more sea.

And God shall wipe away all tears from their eyes; and there shall be no more death, neither sorrow, nor crying, neither shall there be any more pain: for the former things are passed away.

Or so the watchman dreamed . . .

Click on the images to enlarge.

Back to the Tempest track list page.

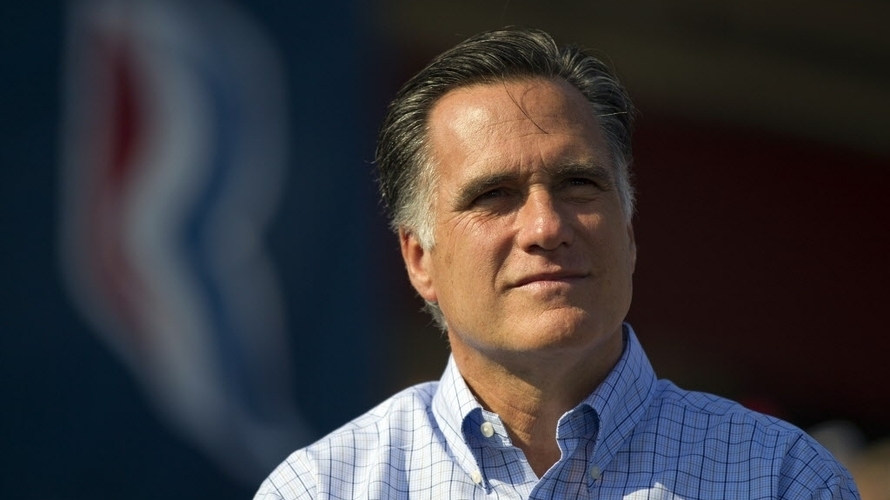

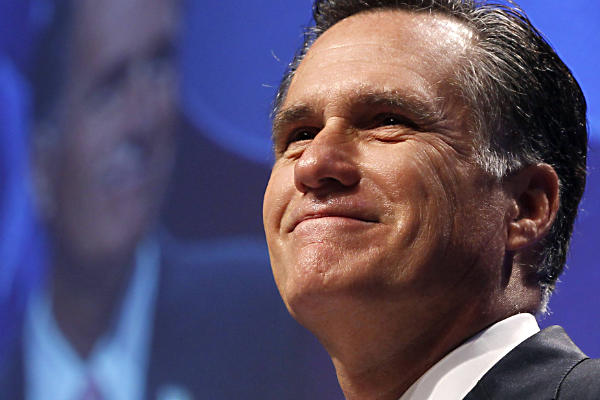

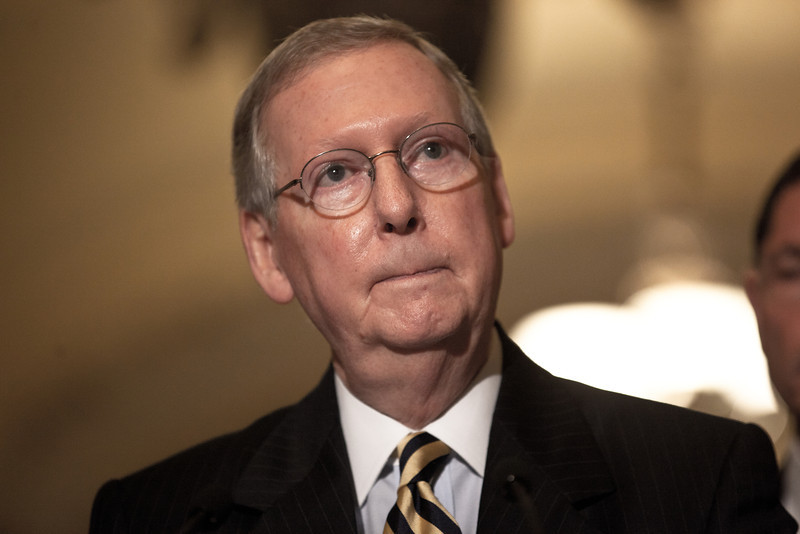

VILE AND DESPICABLE

Mitt Romney’s statement yesterday — that Barack Obama’s first response to the death of our ambassador to Libya was to apologize to those who killed him — was as vile and despicable as any ever made by an American politician, much less one running for President on a major party ticket. It completely and irrevocably disqualifies him for the office.

Until this statement, I had thought of Romney as a vacuous opportunist, a stooge of the plutocracy much like Obama, but I feel differently now. I think Romney is a moral whore, a truly wicked human being — a man who would suck Sheldon Adelson’s withered old dick at a fundraiser in order to live in the White House.

Until now I could never imagine voting to give Obama a second term, and I still find the idea of that nauseating, but I’m considering casting such a vote solely as a protest against the very idea of a man like Romney engaging in national politics. I’d consider voting for almost anyone to make such a protest.

Romney needs to be hounded out of national politics in humiliation and disgrace, and anyone who continues to support him needs to repent of the idea immediately in deepest shame.

TEMPEST TRACK BY TRACK — TIN ANGEL

This is the one song on Tempest that I can’t quite make sense of. It’s a classic murder ballad in the folk tradition — gangsta folk, as such songs have been described. I can see how such a song fits into the dark and violent landscape of the album, but Dylan has been content to simply regurgitate the form.

The king figure in the narrative is called “the boss”, and before he embarks on his murderous deed he cuts the wires to the house where his adulterous wife is dallying with her lover — but aside from anachronistic details like this there’s no real effort to make the tale contemporaneous.

Creating a new version of an old narrative ballad, with a few personal elaborations, is part of the folk tradition, of course. It’s a respectable endeavor — but Dylan usually elaborates more drastically, more imaginatively.

Perhaps one should admire his humility before the form, his ambition to take it just a short ways down the road. I don’t know. As I say, the song works perfectly well in the context of Tempest — it has a droning, insistent rhythm, over which Dylan delivers quirky readings of quirky lines. The overall effect is spooky and unsettling. I just can’t see that it adds much to the murder ballad tradition — but maybe I’m missing something that will reveal itself in time.

Back to the Tempest track list page.

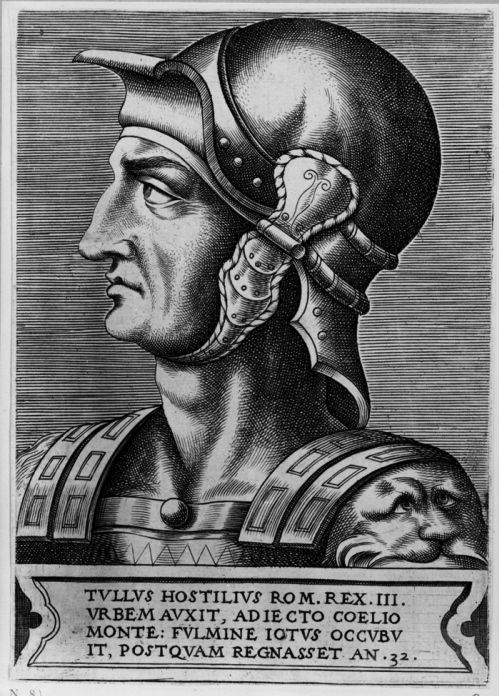

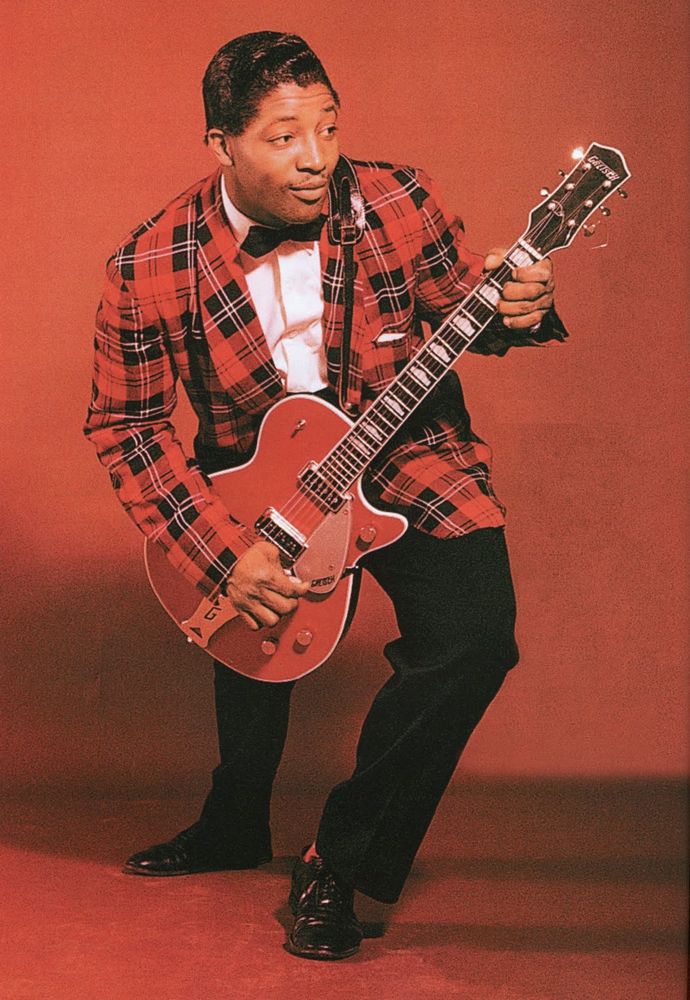

TEMPEST TRACK BY TRACK — EARLY ROMAN KINGS

A number of Dylan fans I know have nominated this song as the clunker among the Tempest tracks. The lyrics are brilliant, but musically the song is slightly monotonous, at least at first listening.

It uses the basic musical structure of Bo Diddley’s “I’m A Man”, with its repetitive stop-time figure. (As Peter Stone Brown points out in his excellent review of Tempest, both Diddley’s version of “I’m A Man”, as well as Muddy Waters’s, a. k. a. “Mannish Boy”, derive from Willie Dixon’s “Hootchie Coothcie Man”.) In the Chicago blues tradition, this structure is used as a platform for ornamentation by the vocalist and the instrumental soloists, which can inflect the repetitive figure in various exciting ways.

Dylan’s vocal doesn’t quite do this, but the more I listen the more I feel that David Hidalgo’s double-tracked accordion fills do. They are sort of ghostly, like echoes of the guitar or harmonica fills we’d expect to find in a more traditional blues arrangement, giving the track the feeling of a ghost blues. If you pay close attention to them, the music feels anything but monotonous, and the driving force of the ensemble keeps things lively all the way through.

Lyrically, the song is a kind of road map to the apocalyptic landscape of the album as a whole. The “early Roman kings” seem to be symbols of the wicked men ruling America today. They are vicious, supernaturally powerful, bent on domination and horrific violence. They are cousins to Tweedle Dum and Tweedle Dee from Love & Theft.

But Dylan, in the person of the narrator here, seems determined to fight fire with fire — to combat the ghoulish kings on their own terms. “You want to fight dirty?” he seems to be saying. “O. k., I’ll show you dirty.” The reference to the virile boasting of “I’m A Man” is clear. “I ain’t dead yet — my bell still rings.”

Dylan is definitely writing protest songs again, though they’re not political in any specific way, nor do they have any of the high-minded moral pleading of his protest songs from the Sixties. Dylan seems to feel that the time for pleading and persuasion has passed — it’s a time for fighting. On another song on the album he sings, “You can stand and fight or you can break and run.” There don’t seem to be any other choices.

In Early Roman Kings, Dylan gives the impression that he relishes the contest. Having decided to enter the fray with both fists flying, he sounds exhilarated. For an album that’s relentlessly dark and confrontational, relentlessly apocalyptic, the joy Dylan seems to be taking in the music is curious.

It may be the joy that the 300 Spartans felt at Thermopylae when they decided to fight to the death against impossible odds. They knew they would win, even after they were all dead. They knew the battle would mean something forever.

Back to the Tempest track list page.

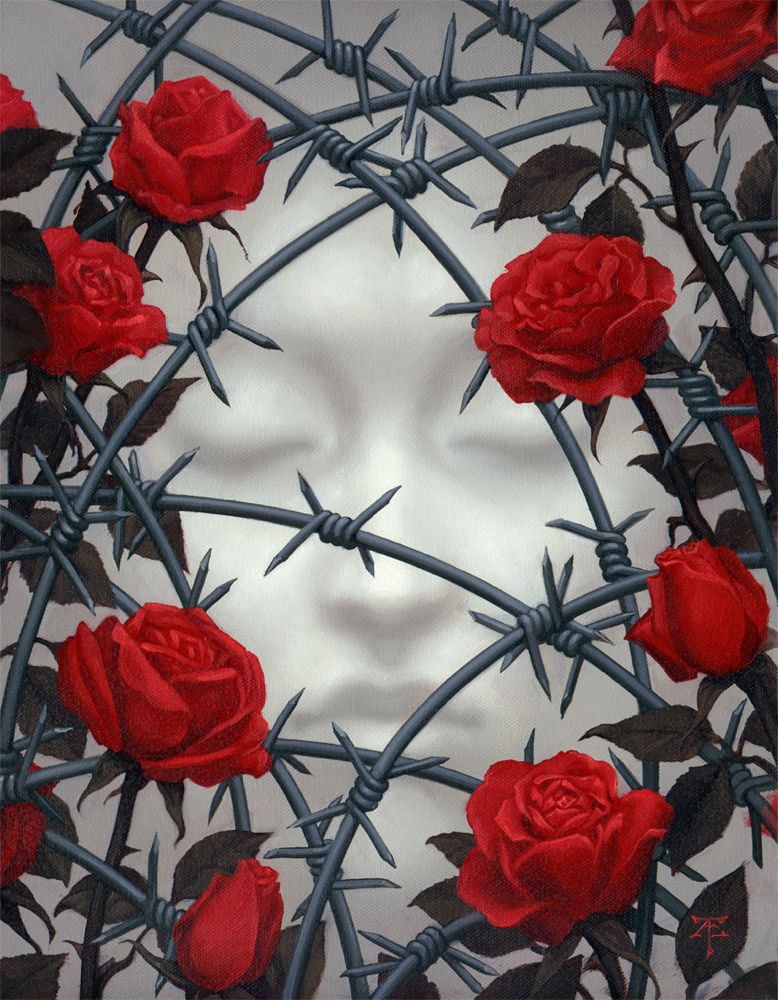

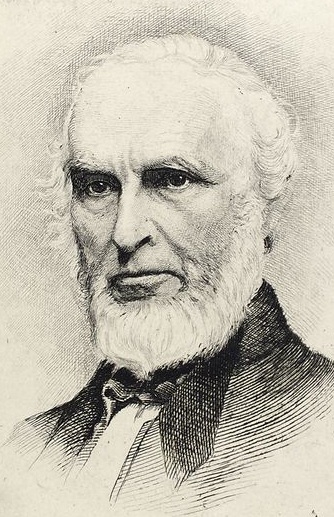

TEMPEST TRACK BY TRACK — SCARLET TOWN

Scarlet Town, where the narrator of this song says he was born, is also of course the hometown of Barbara Allen, who figures in one of the most famous of English ballads, first printed in the late 17th Century but probably dating from much earlier. Dylan performed the song in his early club days, and an achingly beautiful version survives in a live recording from 1962.

In Dylan’s new version on Tempest, Scarlet Town is peopled with many more figures than the doomed lovers of the ballad. The ghost of John Greenleaf Whittier (above), 19th-Century New England poet, hymn writer and abolitionist, seems to be in residence there, referenced in many quotes and images from his poetry.

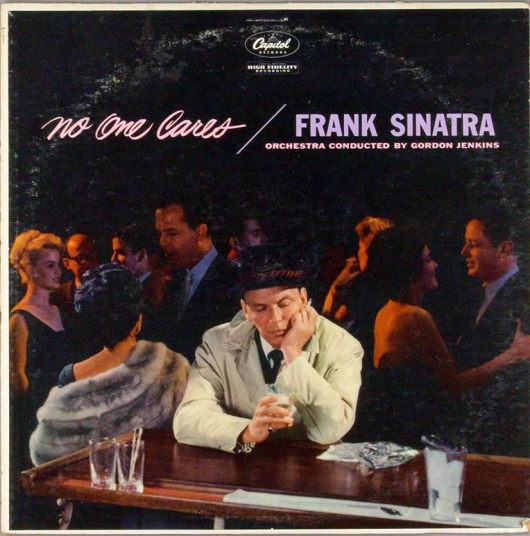

At a local bar, the narrator sings, “Set ’em up, Joe, play ‘Walkin’ the Floor’, play it for my flat-chested junkie whore.” In these brief lines Dylan manages to summon Frank Sinatra, Ernest Tubb and (via Tristessa) Jack Kerouac, all of whom can testify, in terms sophisticated, prosaic or depraved, to the heartaches of hopeless love, like the love for Barbara Allen that killed Sweet William in the ballad.

The slightly ominous but elegiac arrangement of a sweet melody wanders along like the narrator through a place very much like Desolation Row, without the theatrical spectacle, a ghost town that has been abandoned by its flesh-and-blood residents but is lively with spirits.

Sweet William dies once again for the love of Barbara Allen — the narrator identifies with him. “I’ll weep for him as he’d weep for me.” There are hints of a larger catastrophe ravaging the land — “beggars crouching at the gate . . . help comes, but it comes too late.” The old faith seems to be failing — “I touched the garment, but the hem was torn.” People are fighting their fathers’ foes. “The end is near.”

Still, somehow, love abides, if only as hope. “Put your heart on a platter and see who bites — see who’ll hold you and kiss you goodnight.” Regret permeates everything — “Lot of things we didn’t do that I wish we had.”

Finally the ghosts convene in the bar to raise glasses to ruined loves, but the narrator won’t despair — decides to stick with love, doomed or not. It seems to be the only way out of this desperate town, if there is one.

Back to the Tempest track list page.