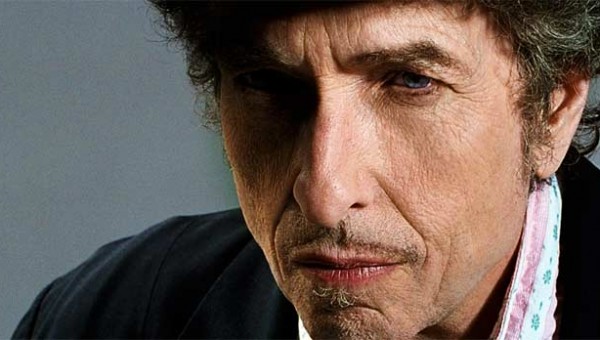

This song is so convoluted, so twisted in on itself with double meanings and paradoxical juxtapositions, that it can’t really be analyzed logically. Dylan is in prophetic mode here, possessed by rage over wrongs done to him, but also over political wrongs, some kind of desecration of the nation that needs to be redeemed.

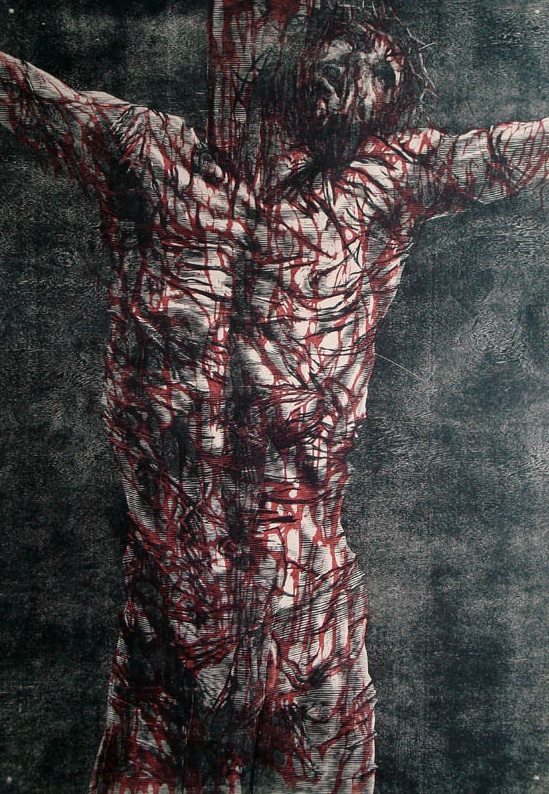

It seems at first to be a song about vengeance — “I’ll pay in blood, but not my own” is the recurring line, which certainly sounds like a violent threat. But it could also refer, ironically or slyly, to the atonement of Christ, who pays for our sins with his blood, not our own.

The lyric never settles down or resolves into coherence, on this point or any other — the lines collide, resonate, seeming to follow chaotic emotions that can’t be pinned down. They’re sung with great feeling and conviction, though, which only adds to the song’s strangeness.

Nevertheless, the final effect is somehow exhilarating — perhaps just from the letting off of steam, the expression of a rage that seems to be part of the culture now, a sense that enough is enough, that things have to change, violently if necessary.

Ever since Love & Theft Dylan has been salting his songs with threats of violence against his “enemies”. I’m not sure what these threats mean to Dylan, or how he wants us to take them.

Some of the threatened violence appears to be directed at his personal enemies, as in the line from “Floater” borrowed from Nathan Bedford Forrest (above) — “If you ever cross my path or interfere with me again you will do so at the peril of your own life.” Some of the violence appears to be directed at enemies in an apocalyptic war of good versus evil, as in these lines from “Ain’t Talkin'” from Modern Times — “If I catch my opponents ever sleepin’ I’ll just slaughter them where they lie.”

These threats often show up in songs of devotion and spiritual aspiration, where they seem out of place, to put it mildly. They certainly seem to contradict Dylan’s obviously Christian, though certainly eccentrically Christian, beliefs. Of course, Dylan often sings in personae that don’t necessarily mirror his own, but these images of violent revenge are really starting to mount up now.

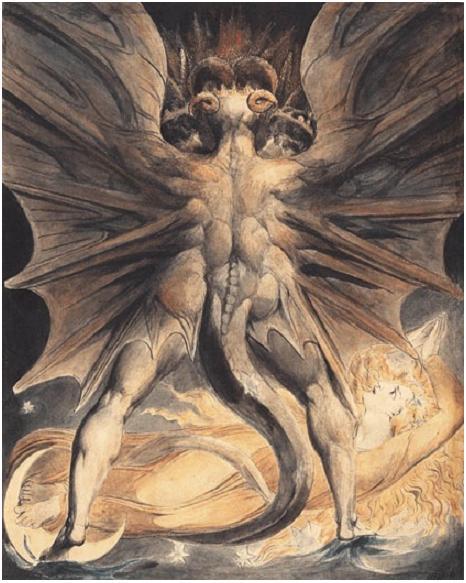

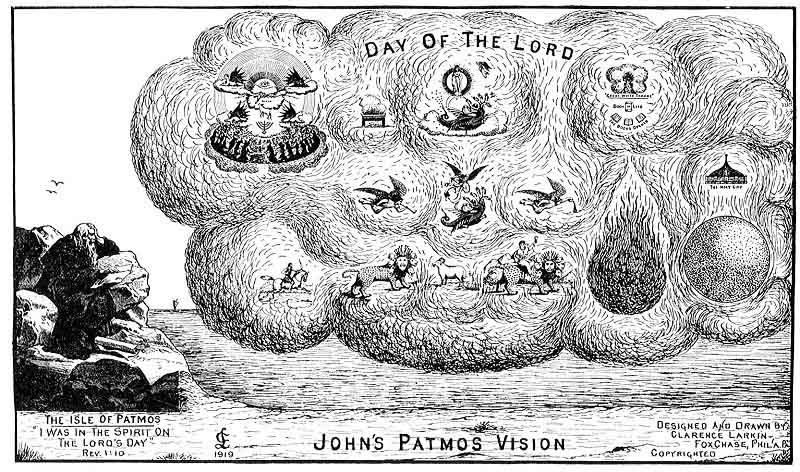

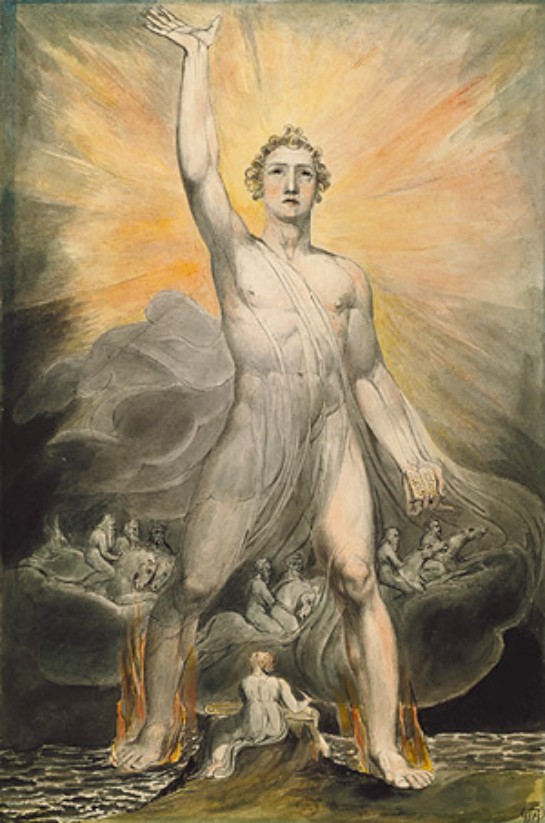

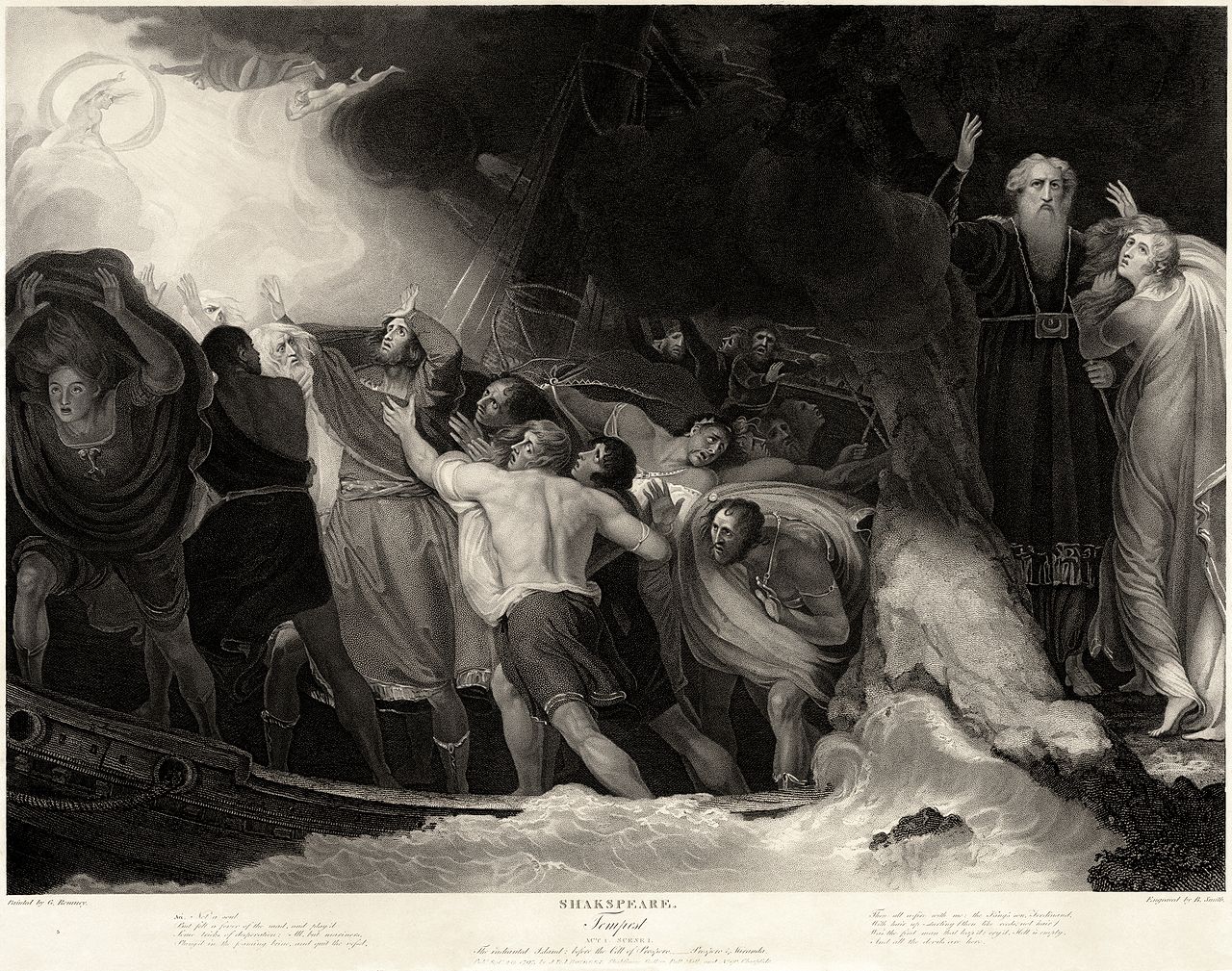

In the song “Tempest” on this album the captain of the Titanic spends his last moments reading the Book Of Revelation. It may be that Dylan has been doing the same, and it may be that the righteous violence in Dylan’s 21st-Century albums is a metaphor for spiritual struggle, which is the way some people read the depiction of apocalyptic warfare in The Book Of Revelation. William Blake, the most pacific of men, certainly read Revelation that way, and echoed its violent strife in his prophetic works as metaphorical conflict, “mental strife”, as he put it.

There is no section of The New Testament more problematic than The Book Of Revelation. Christians have been debating its authorship, authority and meaning from the time of the earliest recorded histories of the church. Thomas Jefferson called it “merely the ravings of a maniac, no more worthy nor capable of explanation than the incoherences of our own nightly dreams.” Some might say the same of Tempest, or parts of it. Others, following Freud, might say that our dreams are only superficially incoherent — that read correctly they make perfect sense.

I’m inclined to think that Tempest makes perfect sense — not worldly sense, perhaps, but sense — and that it is, at the very least, worthy of the closest reading. My friend Paul Zahl tells me that the German theologian Jürgen Moltmann sees The Book Of Revelation as something given to oppressed peoples to imbue them with images of strength and triumph in dark times.

Given Dylan’s view of our own dark times, this may be the best insight into his use of violent apocalyptic imagery, representing a kind of yearning for strength and triumph, barriers against despair.

Back to the Tempest track list page.