Paul Zahl reflects on what’s not being talked about in this year’s campaign for President — basically, everything that’s really important:

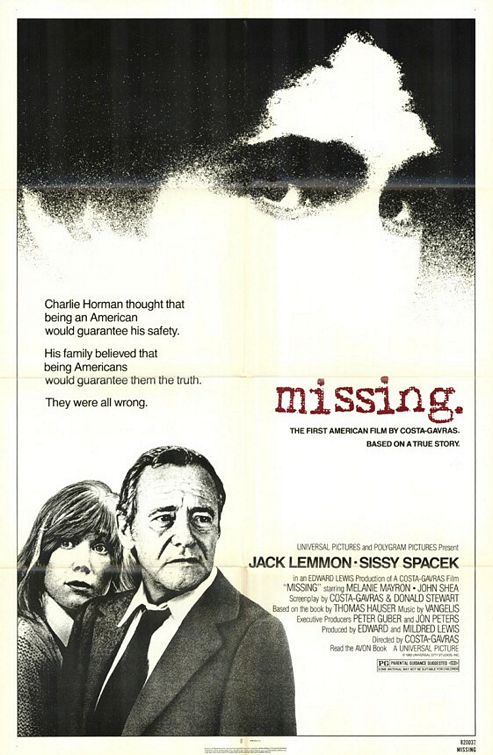

In the 1982 movie entitled Missing, directed by Costa Gavras, the “Ed Horman” character, played by Jack Lemmon, says to two U.S. Embassy culprits, “At least I live in a country where people like you can be prosecuted for crimes like this one.”

The line becomes ironic, as no one from our country ever was prosecuted for complicity in the murder of Mr. Horman’s son, Charles, in the aftermath of the coup against Salvador Allende in l973 in Chile. The complicity of United States officials in Santiago was later confirmed when a previously classified State Department memo was released during the Clinton administration.

Because Jack Lemmon’s performance as “Ed Horman” is so poignant and so real, it is hard not to identify with him, the grieving father, a devout Christian Scientist businessman from New York City, no matter what your politics are. You identify with the human drama — it really happened, and I myself knew Ed Horman and Charles personally — and you are filled with feeling for him, and you agree with his indignation. He left Chile with the faith that justice would be done, at least in America. It wasn’t. Justice was never done. Mr. Horman died without seeing justice done on behalf of his son.

And what about the violators of habeas corpus at Guantanamo Bay? And the makers and approvers of the “hit lists” of people to be eliminated without capture during an undeclared war? And the idea that extreme distanced combat, conducted by robots and therefore as impersonal as you could almost possibly get, is a good thing? (I grant you, it is an expedient thing.)

Or our “hit makers'” confidence that the lynching of a North African dictator without a trial, in the immediate aftermath of a US drone attack, was justified? (What did our forefathers and foremothers fight for in 1776? Why did they come here?) Or the people who decided to assassinate a world-historical terrorist, no matter how heinous his crimes, without even the possibility of a trial? (Why did this country take the trouble to try war criminals in 1945 and 1946 at Nuremberg? We knew they were guilty. Why try them? I ask you.)

Poor Ed Horman in retrospect! “I knew him, Horatio.” I remember the week that Charles, the Hormans’ only child, was accepted at Harvard College. Mr. Horman was as proud and beaming a father as you could ever see.

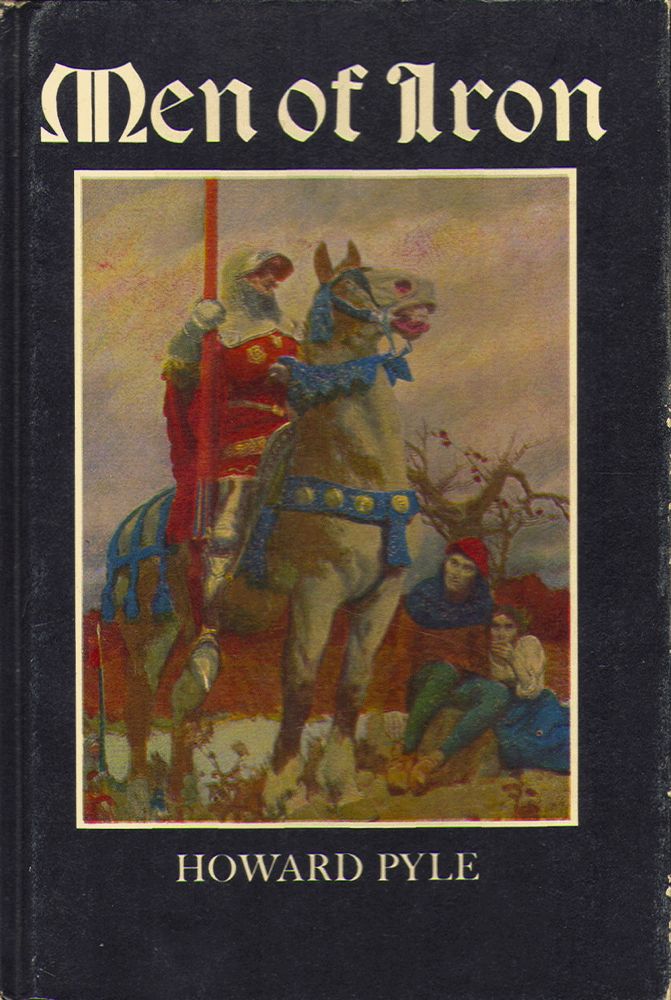

Last night, after my wife and I had watched Missing, viewing the movie doubles for people I grew up with, I went over to the bookshelf where I keep my childhood books. There it was: Howard Pyle’s Men of Iron.

The plate inside simply reads: “This Book Belongs to Charles Horman.” (I’d written my own name in pencil over his — I was about seven.) Charles’ plate has a drawing of a dog over it, the kind of drawing he liked so much, the kind of drawing that his Jack Lemmon father, at the end of the tale, is gathering up to take back home, to his mother.

It seems that our two, or is it four candidates to become President of the United States agree on a point that cries out from the earth for debate. They agree about drones, and Executive decisions to kill without trial (and without oversight), and “Let’s lock the door and throw away the key now” (Jay and the Americans).

Why is there no debate on the new American morality? It has nothing to do with sex and nothing to do with food. It has to do with Double O Seven — the license to kill. On that point, on who exactly is “like a tree planted by the waters” (Psalm 1:3), there is no difference at all.