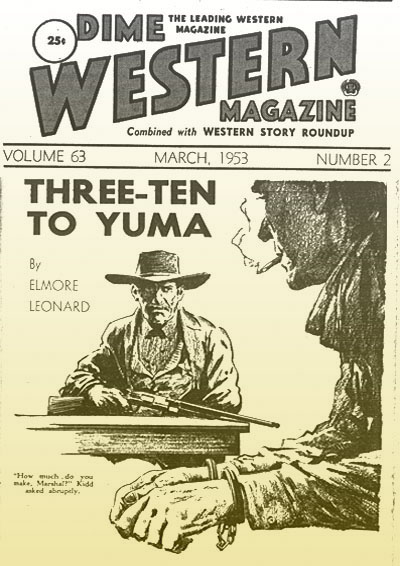

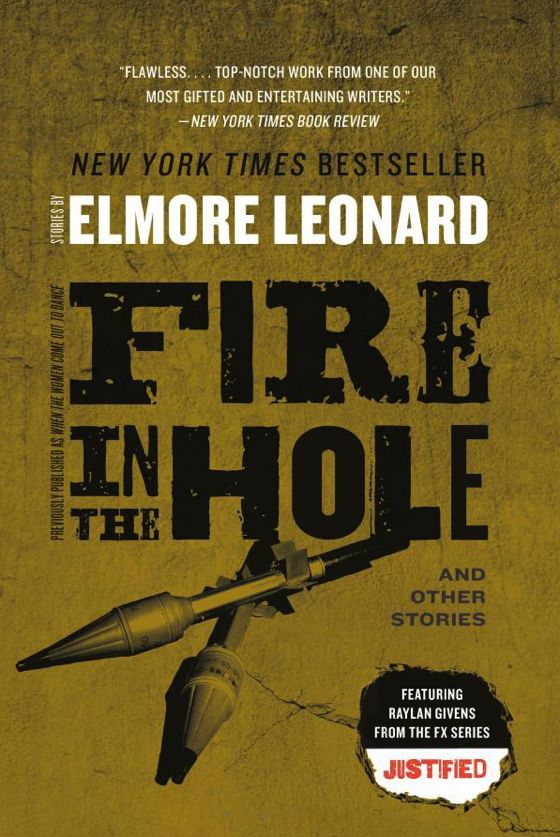

I’ve been working my way through all of Elmore Leonard’s Western fiction — beginning at the start of his career in the early Fifties, when he published his first Western short stories in magazines.

Doing this you can chart his journey as a craftsman and as an artist, because he didn’t start out writing the masterful novels that made his name. He was always a good storyteller, so the early work is entertaining, but it took him a while to master the crackling stripped-down style of his later contemporary thrillers.

He overwrites at times in those early years, giving us too much information about the landscape and the way the characters look. Partly this was to convey a sense of authenticity, proof that he’d done his research, partly it was out of the mistaken belief that such description would make the tale more vivid. He eventually learned that it does just the opposite — the more description you leave out, the more the reader’s imagination has to work and the more engaged he or she becomes in the tale.

From the start he was interested in strong, active female characters, unusual in the Western genre, but it took him a while to learn to write from inside the female psyche — one of the most impressive features of his later work. It also took him a while to develop his trademark humor, wry and mordant, rooted in the quirks of his quirky characters.

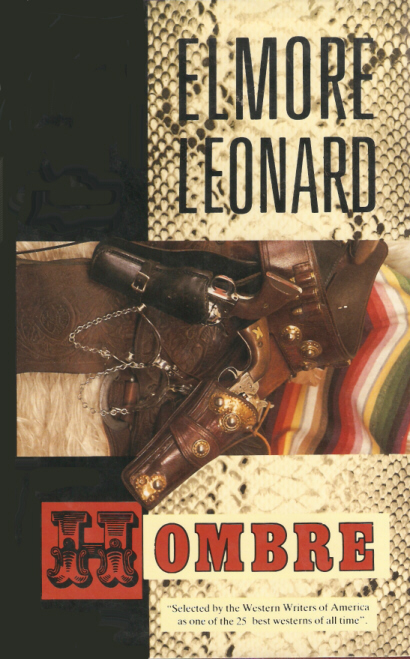

His 1961 Western novel Hombre marks the emergence of Leonard the master storyteller. It has a structure that is both conventional in the terms of the genre and ambitious in voice. In it, as in John Ford’s Stagecoach, a group of passengers on a journey, most strangers to each other, find themselves in peril, morally and physically, and must try to work together to save themselves. The story is narrated, however, by a secondary character, who is baffled much of the time by the motives and interior thoughts of his fellow passengers.

This points the way to Leonard’s mature style, in which the motives and interior thoughts of the characters emerge more from action and dialogue than from authorial commentary.

The protagonist of Hombre is the first of Leonard’s great flawed heroes — taciturn men who proceed according to a private code not always apparent to those they interact with, or to the reader, until some extraordinary act or decision reveals their fundamental nature.

By the time of Hombre, though, the market for Western fiction was drying up. Leonard stopped writing fiction for five years, supporting himself as a copywriter. He roared back later in the Sixties with the first of his contemporary thrillers, which got better and better, and created his current reputation.

Reading the early Western fiction now is pleasurable for anyone who enjoys the genre, but it also offers a fascinating look at the stages of Leonard’s slow and dogged development as a writer, probably the best fiction writer at work today.