How did Pope Francis make his way up through the hierarchy of the Catholic Church? It’s like finding Edward Snowden heading up the NSA.

Monthly Archives: December 2013

THE HORROR, THE HORROR

MERRY CHRISTMAS

A CHRISTMAS PAST

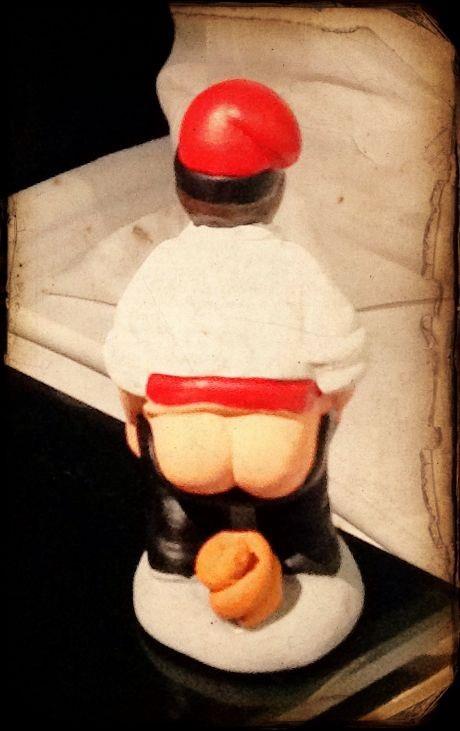

SATAN HATES IT

WHO KNEW?

This is Caganer, the figure of a little boy taking a dump, who appears in traditional Catalan nativity scenes. He dates back at least to the 18th Century but no one knows what his presence is meant to convey. Suggestions have been that he’s there to amuse small children, to remind us that we never know when salvation will arrive, to show that, at bottom, all human being are equal.

In any case, I can’t think of any reason why he shouldn’t appear in a nativity scene.

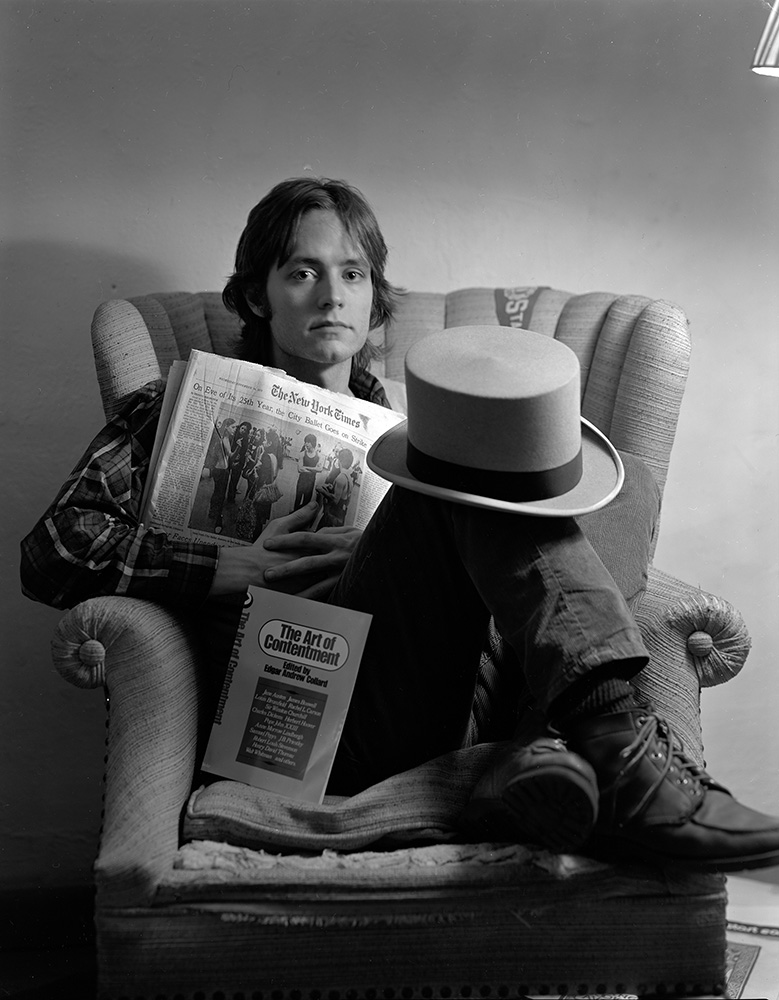

INSIDE LLEWYN DAVIS

There’s a line in a Bob Dylan song — “I know plenty of people put me up for a day or two” — that perfectly sums up everybody’s scrambling days, when you were between fixed abodes, between relationships, between steady jobs, between plans, between dreams . . . when you wore out every welcome you received because you didn’t know where the next welcome was coming from, when you were too proud to go home to mom and dad (and maybe you’d worn out their welcome, too), when you just didn’t know what the fuck you were going to do next.

When you’re young you figure such days will pass, and they usually do, after a fashion, but you never really get over them. Inside Llewyn Davis is about such days in the life of a struggling folksinger in New York in the early 1960s. Its evocation of that time and place, that musical scene, is magical, but it’s the evocation of Llewyn’s scrambling life that makes the film memorable.

It’s not one of the Coen brothers’ most inspired efforts — the litany of Llewyn’s woes gets a bit repetitive after a while. Once you realize that nothing is going to turn out well for Llewyn the narrative loses momentum. And yet . . . Inside Llewyn Davis gets at something, portrays something, that few films ever have.

[Image © Langdon Clay]

I spent many of my own scrambling days in New York in the 70s so the film brings back poignant memories, and a curious personal revelation. I got all, or almost all of the things I dreamed about getting in the 70s and one by one they have all evaporated or come to seem hollow — and I feel today more like that scrambling kid in his 20s than I ever have since the 70s. With one difference — I’m no longer looking for a home in this world, I mean, one that I can rely on. I know that all homes are provisional, as provisional as sleeping on a couch in a friend’s living room.

So it’s heartbreaking to see Llewyn Davis’s heartbreak as he looks for a home, a place for himself. I want to slip him 20 bucks and tell him not to worry — tell him that he’s already as home as he’ll ever be, that life is a perpetual scramble, and worth the discombobulation. Not that he’d listen, anymore than I would have when I was in my 20s.

Click on the images to enlarge.

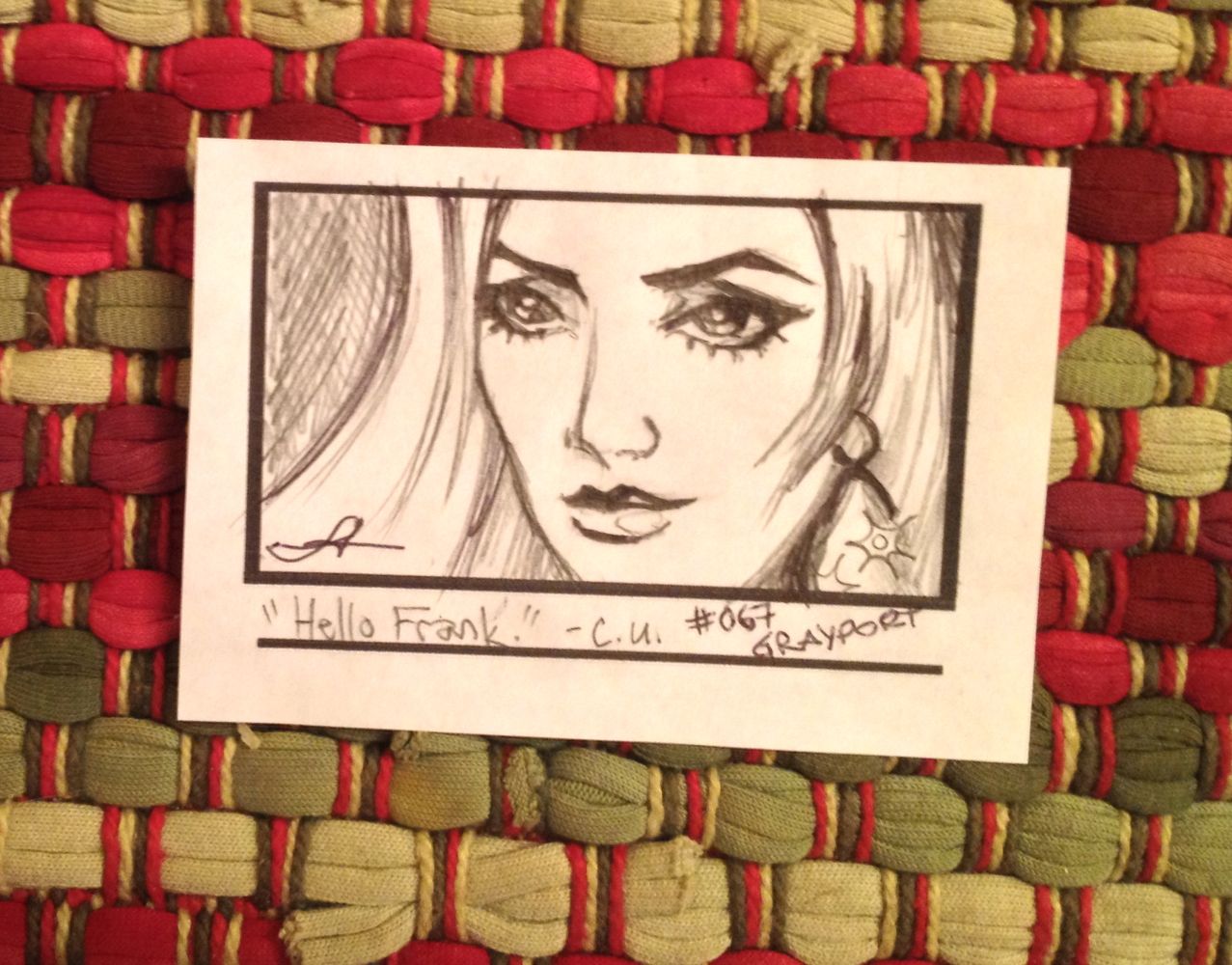

LOOK WHAT I JUST GOT

. . . original storyboard art for the upcoming indie film Grayport, one of the Kickstarter rewards for a modest $25 contribution. Get yourself one here:

Click on the image to enlarge.

SANTA UNMASKED

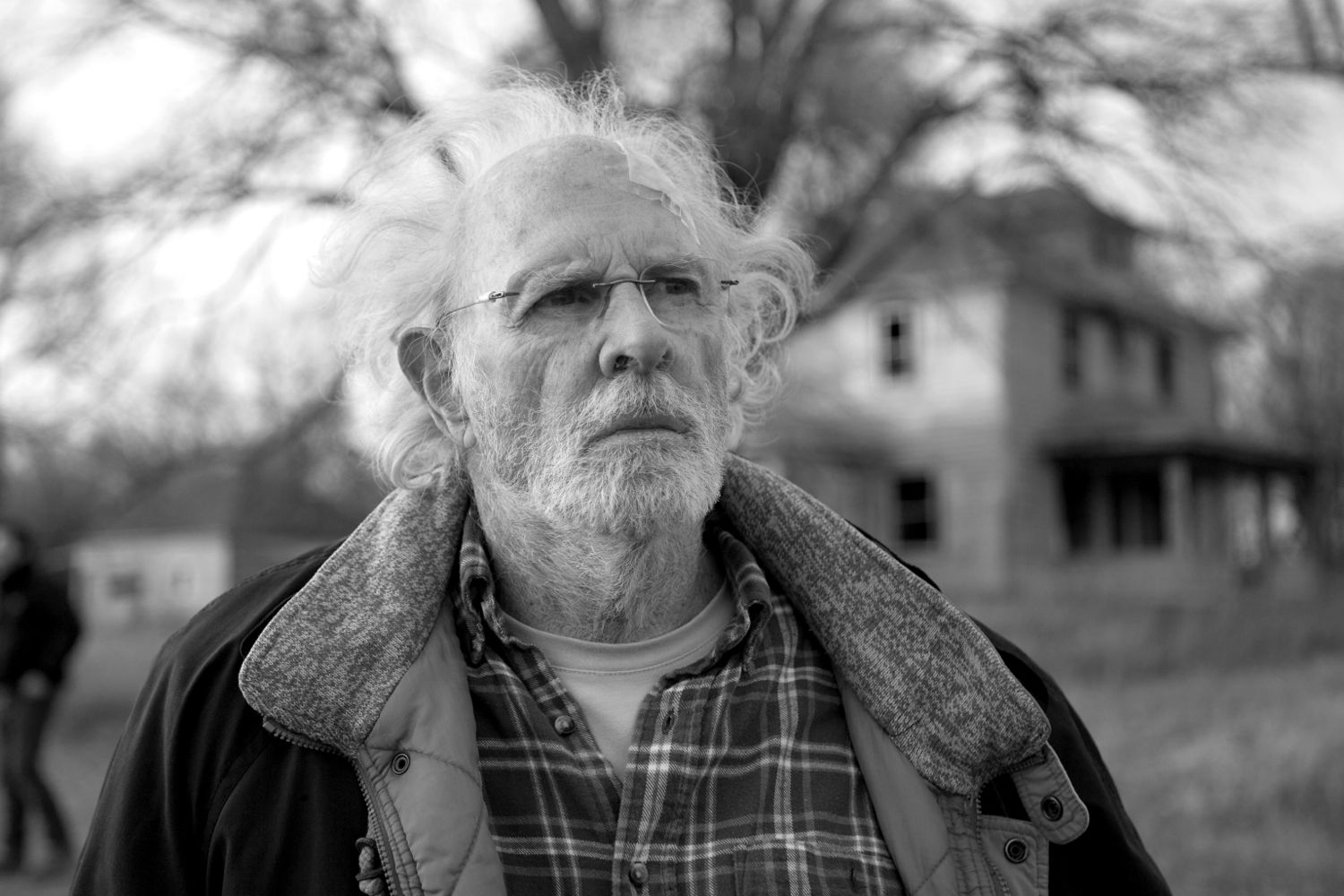

NEBRASKA

I must say I embarked on a viewing of this film with some trepidation. I’ve always thought of Alexander Payne’s films as “watchable” — and if that sounds like damning them with faint praise, well, that’s the idea. They are films with interesting premises set in interesting places and employing interesting actors but don’t add up to much more than a couple of hours of diversion.

Noting that Nebraska was shot in black and white, I feared that Payne had at last decided to make a full-on art film, which I expected to be pretentious and dreary — but Nebraska is neither of those things. It’s a modest, well-observed, beautifully shot movie that doesn’t condescend to its quirky heartland characters and their relentlessly flat world. Instead it takes them seriously, or as seriously as they deserve to be taken, and it loves them, without judgment.

Bruce Dern’s performance sums up what’s good about the movie. Dern is so deep inside the buttoned-up character he plays that he reveals no more about himself to us than he does to the people around him. What might have been a showy caricature of old age becomes instead a moving portrait of estrangement and bewilderment. Dern creates this portrait basically by doing nothing, by reacting blankly to the revelations about his life that the film delivers.

We can read what we want to or need to into his taciturn persona but Payne never prods us into anything. We’re allowed to be amused by the simple-mindedness of some of the characters we encounter, but Payne never patronizes them.

This is the sort of odd, personal, adventuresome yet circumscribed movie that used to get made with some regularity in the 70s. It isn’t a great movie by any means, but it’s an admirable and humane movie — a great rarity on the current scene.

ZOEY’S GUIDE TO REAL LIFE

Matt Barry’s latest — modern youth on the march . . . not.

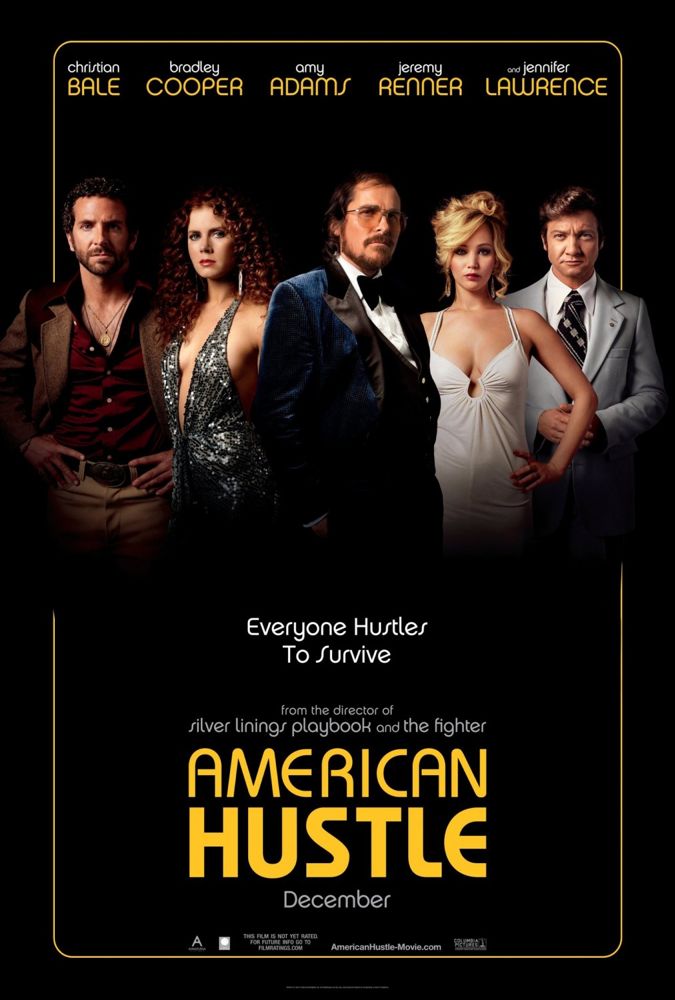

AMERICAN HUSTLE

It’s very difficult to convey just how bad this movie is. It’s got an intriguing premise and a clever plot, but these things exist for one purpose and one purpose only — to give a lot of cool actors a chance to play outlandish, somewhat sleazy “characters”, to overact and mug, just so you know that the actors aren’t really who they’re pretending to be, that they’re being “brave” to essay such roles.

Every other scene is an emotional climax, with shouting, crying, a breakdown or a fit — all those things actors love to do to show off their chops. Here they get to show off their chops almost every minute they’re on screen. It’s exhausting and infuriating, this non-stop display of self-indulgence.

In the middle of it all, though, is a modest miracle — Amy Adams, who actually seems to be inhabiting her role, playing her character from the inside. She can’t redeem the awful dialogue she’s given, but she reminds you what real acting is all about and serves as a kind of rebuke to the posturing going on around her.

The New York Film Critics Circle named this the best picture of the year. What were they thinking?