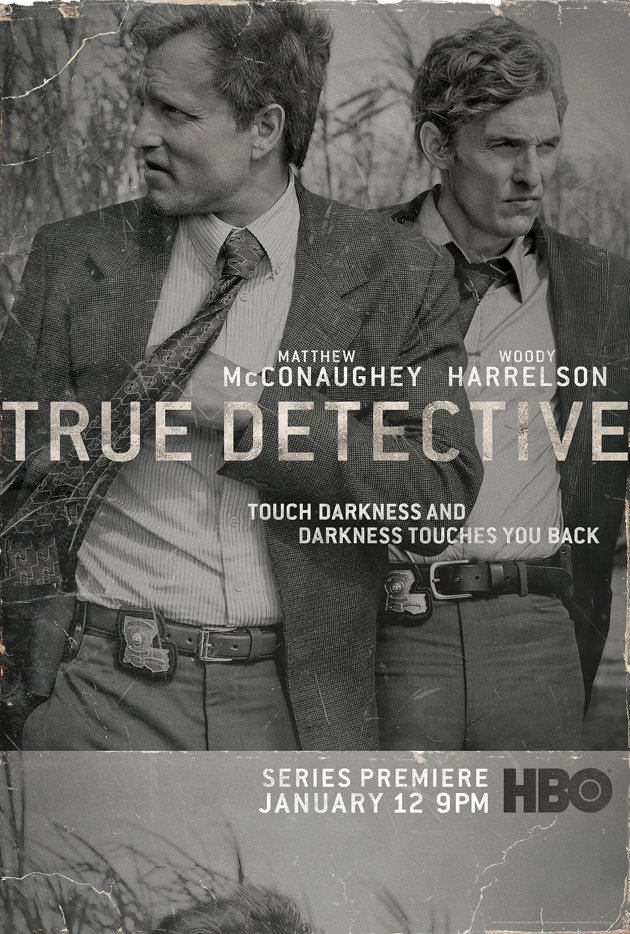

[SPOILER ALERT — don’t read further if you haven’t yet watched True Detective but plan to.]

So it ended up being lurid pulp fiction after all, not a supernatural thriller. The title should have tipped us off about this. Yet the whole thing was a kind of wild fever dream, always teetering on the brink of the plausible — it made you feel unsteady, filled you with dread. Doing this without supernatural elements was a fine achievement and a very satisfying one.

It kept you guessing to the end. When Rust pointed his finger in the direction of the kidnapped sheriff next to the boat and gunshots exploded out of nowhere at the places Rust was pointing, I thought for a second that Rust had been revealed to possess magical powers. But, no — there was a hidden sniper firing those shots, a device perfectly suitable to lurid pulp fiction.

When Rust and then Marty entered the grotesquely decorated maze of Carcosa, the suspense became nearly unbearable — because they should not have been doing this by any rational calculation. They should have gone in together, or waited for back-up. But they had to navigate that maze, whatever the cost — it was a symbol of the maze of the case itself, which they had become obsessed with, willing to risk everything to solve.

Not the least of the risks they ran was madness. Trying to enter the mind of a severely deranged psychotic killer left them on the margin of sanity themselves. But they needed to enter the madman’s story to chart the maze he’d created and destroy it.

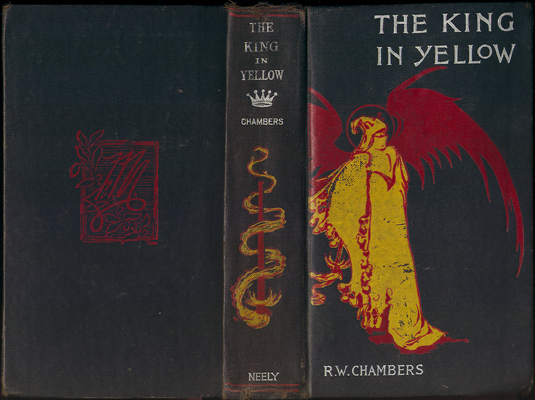

The references to The King In Yellow became clear at last. The King In Yellow was a series of stories about a play that induced madness or despair in people who watched or read it. In other words, a series of stories about a story. That’s its significance to True Detective — not the supernatural element in the original book. Errol William Childress was telling stories about himself through his grisly deeds, which induced Rust and Marty to search for the story that inspired Childress’s story, and its significance. Only by unraveling that story could they change it. In the process, both risked losing their minds.

In the coda after the chase in the maze, a coda that is the true climax to the series, Marty reminds Rust about his youth in Alaska when he’d stare up at the night sky and make up stories. There’s a suggestion that telling stories is the only reasonable response to the forbidding mystery of the cosmos, and that the foundation of all stories is seen in the night sky — darkness versus light.

In the coda, we find that Rust, the bitter nihilist, has found faith — in something beyond death. The supernatural intrudes at last, in the last place we’d ever expect it — Rust’s petrified heart. But it doesn’t appear out of nowhere — Rust’s obsession with solving the case was always based in faith, an idea that stopping a few of the world’s horrors does mean something, does bring a spark of light to the darkness of existence.

Marty points out that the dark holds more territory in the night sky than the light, but Rust won’t let that be the final word. “Once there was only dark,” he says. “If you ask me, the light’s winning.”

That’s his story now, but every step he and Marty took in the course of the series was a part of telling that story, necessary to the creation of that story.