Combat is largely about terrain — natural elevations, depressions, cover, open ground, obstructions. To be a good tactical commander in combat you need to have the mind and eye of a great landscape painter, which is one reason it’s hard to portray combat in prose.

You can read everything ever written about Pickett’s Charge — and sometimes I think I have — but until you go to Gettysburg and walk the ground (above) where the charge was made, you have only a dim idea of what it must have involved, the lethal variables of the event itself.

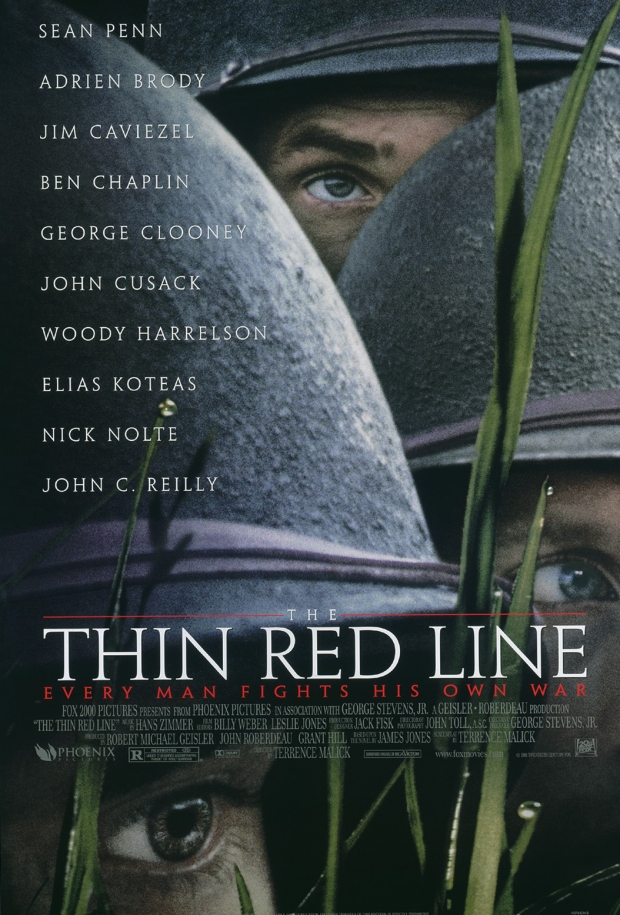

Movies could theoretically do a better job at portraying combat , but rarely do — rarely present us with a comprehensive and coherent view of a battlefield that can be read for the problems of terrain that need to be dealt with in combat. Terrence Malick’s The Thin Red Line is an exception — the assault on the ridge in that film and the engagement in the river are two of the most brilliant and convincing evocations of combat ever created. We not only see the individual agony of the soldiers, we see the conundrum of the terrain they’re faced with, clearly enough to feel on a gut level how terrifying it is.

The film as a whole is a virtuoso piece of filmmaking, evoking places and spaces with a vividness that is almost hallucinatory. It’s probably as close as a non-participant can ever get to the experience of island warfare in the Pacific in WWII. It has its faults — poetic voice-over meditations on the meaning of war that sometimes sound convincing as soldiers’ thoughts but just as often sound like the highfalutin’ mystical musings of the filmmaker.

Malick was moving towards the form his later films like The Tree Of Life would take, in which the mystical voice-over musings would flow into and out of the extraordinary images in a more organic way. It seems to be part of a lifelong project to re-orient viewers towards cinematic images — to promote a deeper reflection on them, a greater appreciation of what they can mean.

Godard was after the same thing in many of his films, as was Kubrick in 2001. It’s not a traditional “avant-garde” strategy, like that of Antonioni, who used conventional images in conventional ways in the service of a fractured, ambiguous narrative — which is essentially a literary ambition.

Malick’s desire to seduce us into a more intimate relationship with cinematic images themselves is about revealing the stories they can tell on their own terms. The Thin Red Line is, on one level, a conventional war movie, a genre piece — it tells a story, or a series of stories, that aren’t exactly unfamiliar. What’s unfamiliar is how deeply Malick draws us into those stories by means that are purely and uniquely and magically cinematic.

Click on the images to enlarge.

To me, what makes this movie the greatest World War II movie is that it’s not about the battle itself or the strategy or why they are on Guadalcanal. It’s about the individuals experience of war and how terrifying that is.

Saving Private Ryan’s opening scene was spectacular, but the Omaha beach scene isn’t about the individuals, its purpose is to show the unforgettable and perilous fight those guys had to go through. The film only does this on rare occasions. Saving Private Ryan doesn’t really show how war changes men, The Thin Red Line does.

The Thin Red Line goes into the individuals experiences and thoughts throughout the entire film. Terrence Malick isn’t interesting in presenting these men as warriors, they are ordinary men thrown into an unimaginable situation and this experience turns them into extraordinary men, but psychologically damaged men as well. Movies like the Thin Red Line are scary for filmmakers to make because there is nothing pleasant about the subject matter. I’m not saying Saving Private Ryan is pleasant to us, but part of Saving Private Ryan’s appeal is how accurate they portray battle, not the soldier himself.

Both are great films but for me, the Thin Red Line is a superior film. Great article