Click on the image to enlarge.

Monthly Archives: May 2014

THANKS, PAL

DIAL M FOR MURDER

This is one of Hitchcock’s most fiendishly entertaining movies and one of his most brilliant exercises in cinematic craft.

The movie was based on a single-set play and Hitchcock made a canny choice not to “open it up” for the screen. Almost the whole film takes place in the living room of a London flat, with occasional glimpses of connecting rooms and a hallway outside. The few exteriors in the film are mostly created using back-screen projections, and not very convincing ones, so the apartment set becomes the most convincingly “real” location in the film.

One could probably write a book-length study about the dazzlingly complex ways Hitchcock lights and shoots this set, always with a view to heightening the nightmarish claustrophobia of the intricate thriller plot, the creeping dread that is domestic and contained, proceeding from the suffocating dysfunction of a bad marriage infected by infidelity, hatred and mistrust.

The film was shot in 3D, though it came in at the end of the 3D craze and played out mostly in 2D. There’s now a wonderful 3D Blu-ray edition of the film which allows you to see it as Hitchcock originally envisioned it. For the most part he uses 3D in a restrained way, saving the sensational effects for the few big moments of violence and terror, but even the restrained 3D images allow Hitchcock yet another avenue for exploring the interior set visually, varying the sensual experience of it, drawing you into it.

The acting in the film is uniformly excellent, especially by Ray Milland as a creepily charming villain — and Grace Kelly in 3D is a stunning special effect all by herself.

If you have a 3D capable TV set and a Blu-ray player, add this title to your collection immediately.

A MAXFIELD PARRISH FOR TODAY

ESSENTIAL

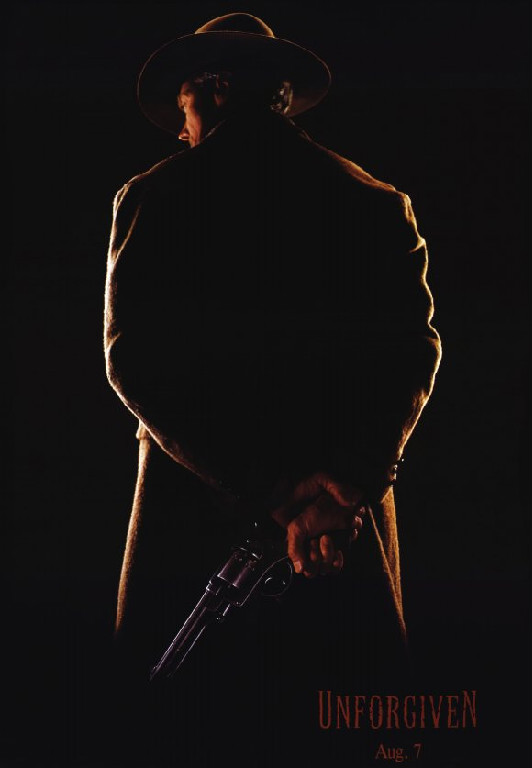

To my mind, this is one of the greatest Westerns ever made, all the more amazing for being made in the 90s, when Westerns of any kind were few and far between.

As I’ve written before, I think all truly great Westerns deal with the themes of shame, honor and redemption. They’re parables on the subject of being a moral person, usually a moral man, a worthy man. Because its setting is the American frontier, the genre is often seen, and sometimes dismissed, as the embodiment of a national myth, a myth about the nature of America itself, and it’s partly that, but it works on deeper and more universal levels, too, which is why it has been embraced internationally.

It’s a genre about achieving full manhood, and sometimes full womanhood, seen as states of moral maturity.

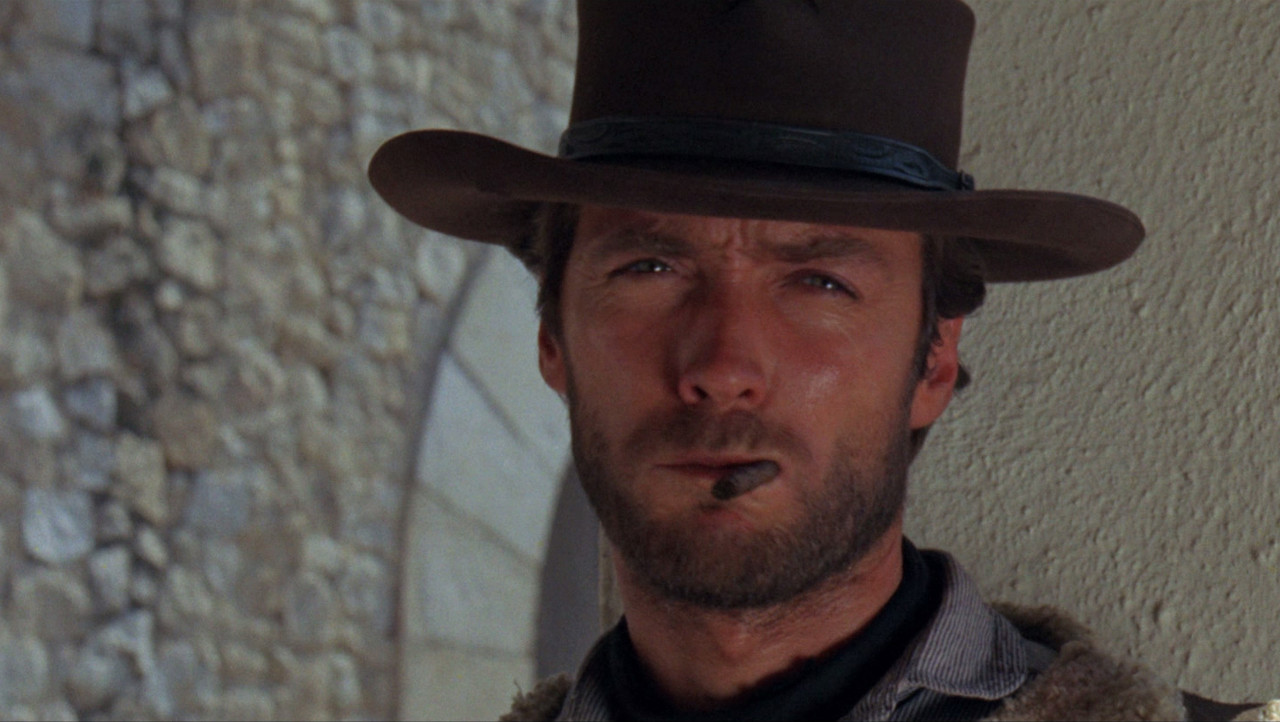

Clint Eastwood’s Unforgiven is an example of how dark and morally problematic a Western can be and still stay within the traditional bounds of the genre. Its protagonist William Munny, a reformed drunk and killer, has put his outlaw ways behind him under the influence of a good woman — but she’s dead and has left him with two small children to raise.

He’s lured into doing one last job as a gun for hire, which he takes on so he can give his kids a new start somewhere far from their failing farm. But he’s also willing to take the job because it involves helping a group of prostitutes get revenge on a couple of cowboys who have cut up the face of one of their number. Munny has killed innocent women in his day, in the course of committing crimes, but has experienced profound remorse for this. Coming to the aid of the powerless women feels on some level at least like a means of redemption.

But things don’t turn out to be so simple. The cut whore for whom revenge is sought doesn’t seem all that passionate about revenge herself. One of the cowboys who wronged her is not such a bad guy. Munny’s two cohorts in the killing for hire become disgusted by the job.

The real villains of the piece turn out to be a sadistic sheriff and an exploitative brothel keeper, to whom Munny will eventually deliver justice — escaping with his moral code compromised in some respects, honored in others. There is a confused, bewildered nobility in the man which triumphs in the end . . . but just barely.

Eastwood’s film is expertly crafted and acted, complex and disturbing and inspiring all at once. It’s a great work of art. The Blu-ray of Unforgiven belongs in the home of every fan of the movies.

PROPHET

GALLANTRY

In Clint Eastwood’s Unforgiven, when William Munny tries to get his old friend Ned Logan to partner up with him for a hired killing, Logan is uninterested. Like Munny, he’s left his outlaw days behind, and can’t see the point in killing a man unless it involves a personal grudge — certainly not for the usual crimes, rustling or cheating at cards or insolence.

But when Munny says the men he’s been hired to kill cut up a woman, Logan’s attitude changes — he’s shocked and outraged. “Well then, ” he says, “I guess they got it coming.” He signs on for the job with Munny, who seems to feel the same about the deed they’ve been hired to avenge, although Munny himself has the lives of innocent women on his conscience from his days as a drunken thug. Clearly something in him has changed.

They’re doing it for the money, at bottom, but the horror of cutting up a woman takes the moral sting out of it for both of them.

I like to think that if they were told a scumbag like Pike Bishop, leader of The Wild Bunch, ordered the murder of an unarmed woman during the robbery of a railroad office, they’d feel the same. They wouldn’t ride off to avenge the murder for the sake of justice alone — they’re not knights errant — but they’d feel entitled to take money to kill Bishop, because he’s got it coming.

This is the difference between real men, however damaged they may be, and frontier scum like Bishop — an innate sense of gallantry and decency towards women that years on the wrong side of the law can’t erase.

Click on the images to enlarge.

DEAR MARILYN

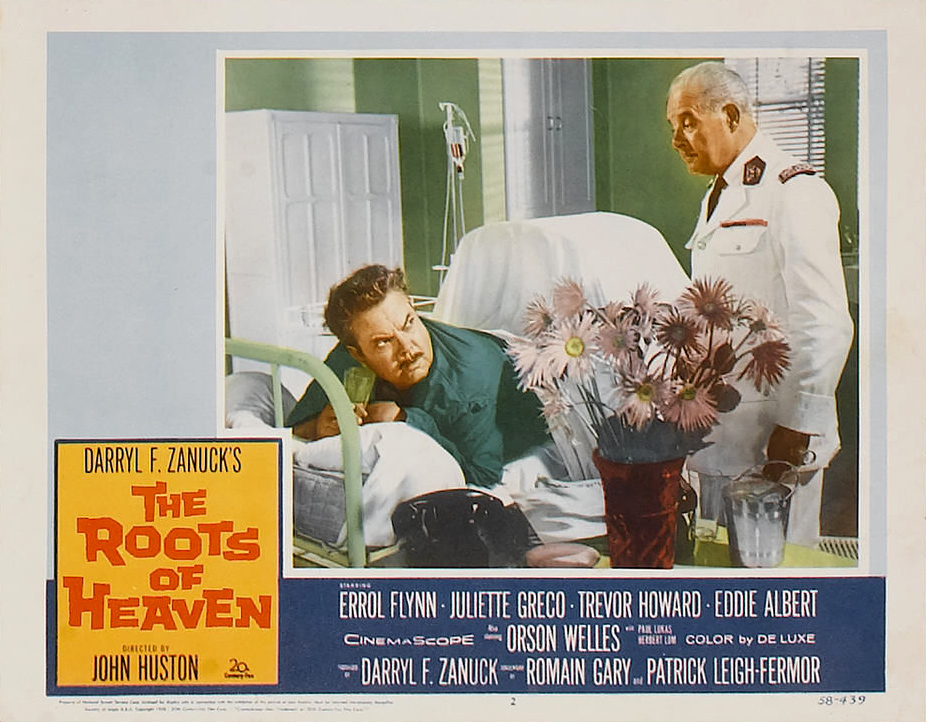

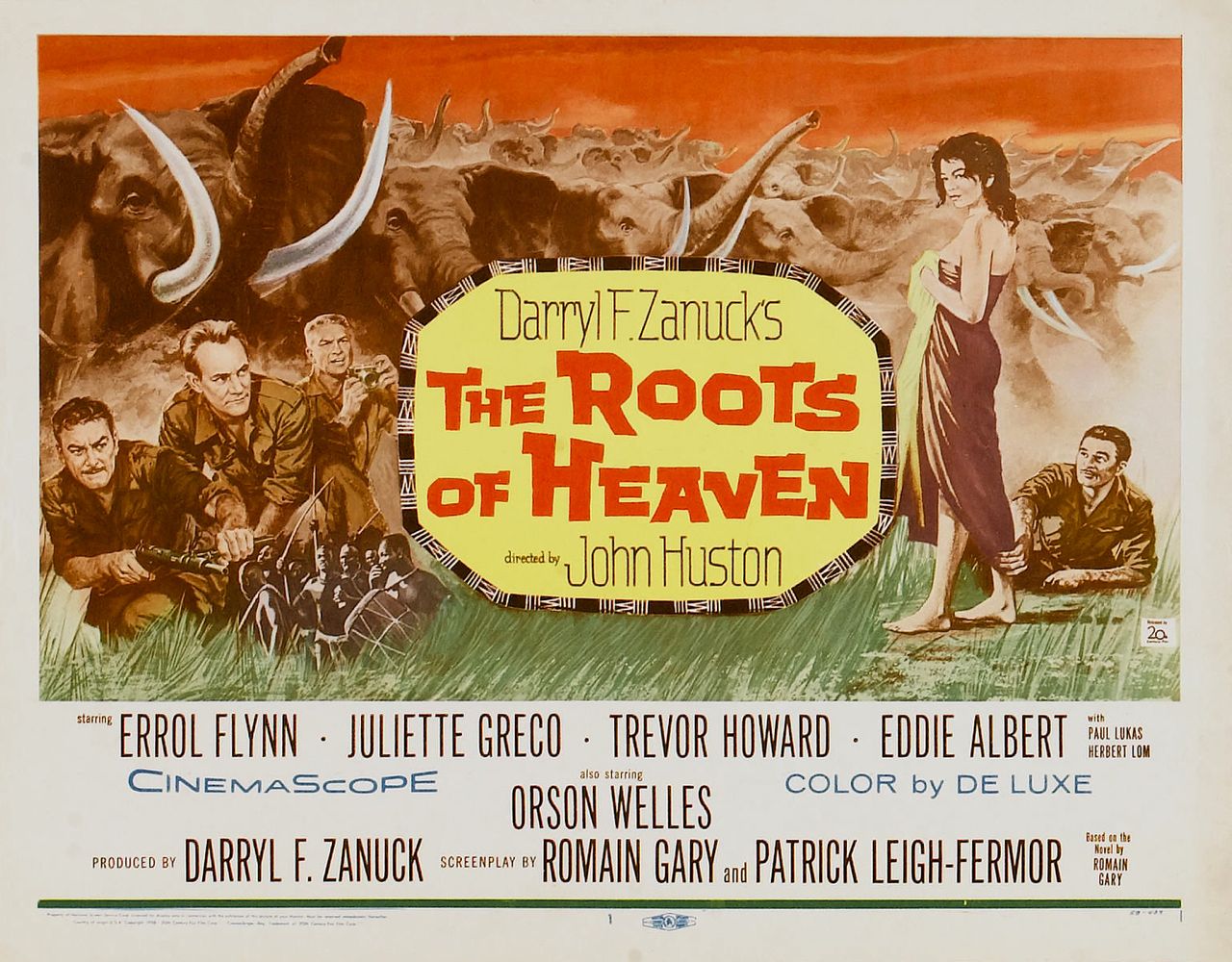

THE ROOTS OF HEAVEN

It’s been said that the deal is the true art form in Hollywood, and there are indeed some films in which the deal defines the work, is the central meaning of the work. There were many such films in the 50s and 60s, when the studios were in decline and big international productions were cobbled together by clever producers marshaling elements from disparate sources.

The Roots Of Heaven, from 1958, strikes me a such a film. It’s a movie based on a prestigious novel by Romain Gary, directed by Hollywood legend John Huston, and featuring several marquee-name actors like Erroll Flynn and Orson Welles. These elements are the film’s principal raison d’etre — you don’t get a sense that any other vision or passion fueled the project.

The “elements” deliver, for the most part. The story is interesting, there are a few wondrous cinematic passages engineered by Huston, Flynn and Welles have their delicious moments. But the film has no core, no defining energy. What you find yourself thinking about as the film dawdles along is Daryl Zanuck’s calculation — “If I throw all these attractions into the pot, the stew will be irresistible!” But there’s more to a stew than its ingredients — there needs to be a chef involved who knows how to cook, how to make a savory meal of the thing.

Sometimes just leaving out the salt, or putting in too much salt, is enough to wreck the dish. Zanuck’s major miscalculation was casting his girlfriend of the time, Juliette Gréco, in the female lead. She just didn’t have the star power to head a cast like this. Casting Trevor Howard in the male lead opposite her wasn’t entirely Zanuck’s fault — William Holden dropped out of the role before shooting started and Zanuck had to take what he could get in order to keep the production together. Howard is a fine actor but again didn’t have the star power to carry a picture like this.

In any case, Zanuck’s recipe was good enough to attract financing — even if it wasn’t good enough to make for a memorable repast. The film is fascinating and enjoyable enough, which perhaps goes to show that the deal can sometimes be a form of entertainment as well as art.

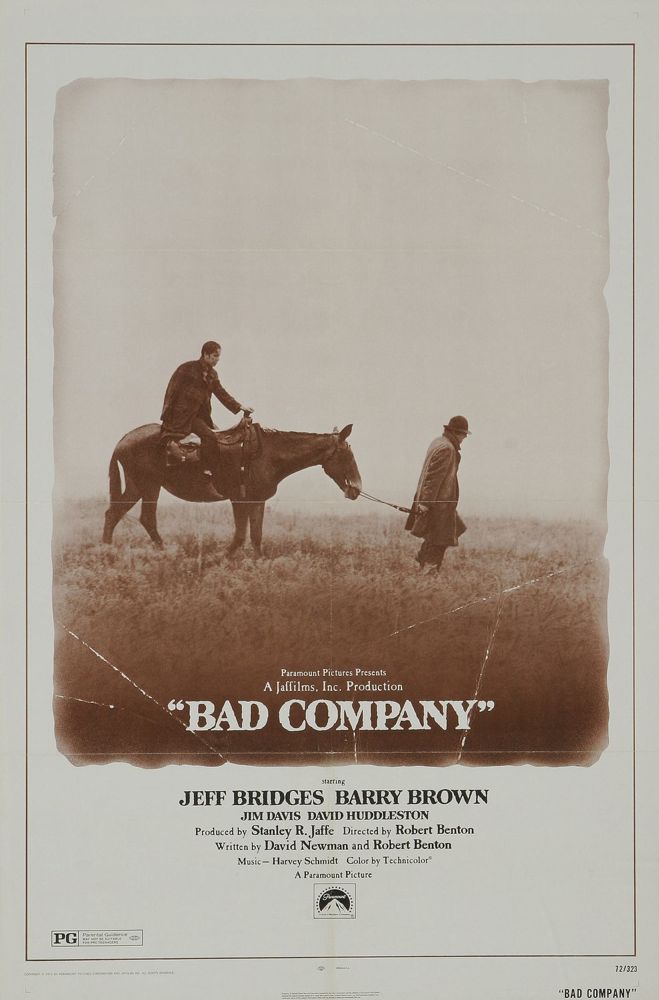

BAD COMPANY

Robert Benton’s first directorial effort, Bad Company, from 1972, is a bad film and a bad Western, too. It’s one of those revisionist oaters from the 70s which takes delight in deconstructing the myth of the frontier, showing it as a sordid and depressing place.

It concerns a gang of young men who light out for the territory during the Civil War, to find fame and fortune and/or evade getting drafted into the Union army. It takes forever to get them moving west, in a long prelude to the actual adventure which mostly involves their cute antics as petty thieves.

It proceeds thereafter in a series of vignettes — robbing farmyards, getting robbed by bandits. Some of these episodes are involving, some repetitive. There’s one really well done scene involving a running shootout in a forest filled with leafless trees.

The dialogue feels synthetic throughout, modeled inexpertly on the vernacular style of Mark Twain.

By the end, the two main protagonists have graduated from a life of petty thievery to a life of armed robbery. So much for the American Dream. So much for the sodbusters who turned the desolate plains into a breadbasket for the world.

The film’s one shining virtue is its cinematography, by the late Gordon Willis, who conveys a vision of the plains that is both beautiful and forbidding. It’s the only real reason to watch the film but, Gordon Willis being Gordon Willis, it’s reason enough.

SHORT TAKE: ROCK-A-BYE BABY

SHORT TAKE: RKO 281

This HBO dramatization of the making of Citizen Kane and the controversy it caused is shockingly bad. It plays fast and loose with the actual historical facts for no reason that I can discern since the actual facts are way more interesting than the ones they made up.

James Cromwell gives a pretty good impersonation of William Randolph Hearst but the rest of the cast is uniformly lame, though I’m not sure how much the actors can be blamed given the synthetic dialogue they’re saddled with.

Not worth a look even if the subject interests you.

THE FRONTIER

ESSENTIAL

It’s a shame that Citizen Kane has a reputation as “the greatest movie ever made”, as a pinnacle of cinematic art. It’s not an art film at all — it’s a grand entertainment, a rattling good melodrama, a work of meticulous craft and wit and joy in the multifarious resources of movies. When you’re watching it, its reputation becomes quite irrelevant because it’s just so damn much fun.

It uses every technique in the cinematic handbook — back-screen projections, matte paintings, stock footage, miniatures. Its greatest glories are its magnificently lit, long-playing, deep-focus, elegantly choreographed studio shots, which are the things most people remember because they’re so beautiful and so involving that you feel you’re inhabiting the imaginary spaces they conjure up.

Those shots constitute the real art of the film, but they’re always in service to the story, to the theatrical but finely calculated and consistently engaging performances. There’s nothing pretentious about the film at all — it’s built to please, to amuse and to move. It has made generations of young people want to become filmmakers, if not always to be great entertainers of the public, because it makes filmmaking look like the best way in the world to have fun, to create magic.

It’s a throwback to the pre-modernist notion that the greatest art is popular art, accessible art, the highest form of entertainment — a notion that informs the works of Homer and Shakespeare and Dickens. That’s its true distinction and the source of its enduring stature in the culture. The Blu-ray edition of it belongs in every civilized home.

THE WILD BUNCH REDUX

I’ve always disliked The Wild Bunch for what I see as its moral nihilism — a violation of the Western genre which it did so much to undermine, and of the very idea of humane art. I don’t think art should make moral judgements or preach moral lessons, but I think it ought to reflect a world where moral questions are important and have consequences.

That’s a personal viewpoint, admittedly, based on my experiences in life, and on my evaluation of great works of art in general. I respect other viewpoints, even if I don’t like or admire them. The idea that human actions have no moral meaning, only a relative meaning based on individual will or style, strikes me as immature, puerile and destructive. It’s defensible as a philosophical proposition, but I reject it, and I don’t think it has ever produced any great works of art.

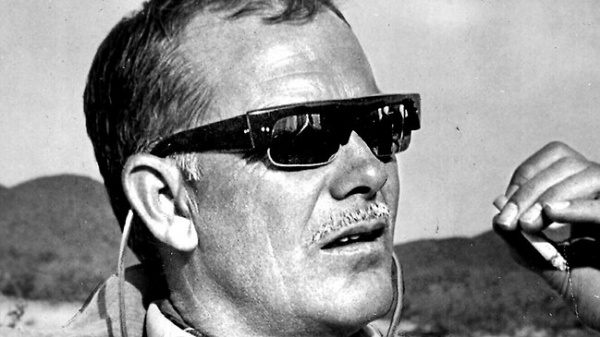

I decided recently to revisit The Wild Bunch, motivated primarily by my respect for the opinions of my friend Scott Bradley (above), who can argue eloquently against the idea that The Wild Bunch is a work of moral nihilism. I also read a few critiques of the film which take the same view.

The Western was losing its cultural prestige in 1969, when Peckinpah’s film came out. The Vietnam war was making many people doubt the ideals America prided itself on, making them wonder if those ideals had always been fraudulent. The Western, embodying a mythology which tended to affirm those ideals, was an obvious target for a revisionist view of such things.

The genre, taken as a whole, had always had room for moral complexity, for good guys who weren’t all that good and bad guys who weren’t all that bad, but it generally held that bad guys could be morally redeemed by honorable acts and that good guys who made bad moral choices would pay a price. Vietnam made some artists, and a big segment of the audience, wonder if that formula, as applied to America in Westerns, was meaningless, and always had been.

As the 60s progressed, Westerns got edgier and darker, and more ironic. Spaghetti Westerns leaned heavily on an irony verging on outright farce. They tended to keep the moral distinction between good guys and bad guys, but they presented the conflict with a wink, suggesting the whole thing might be a joke. Western fans beginning to doubt the genre could have it both ways, rooting for the good guys while not taking them too seriously.

In his 1968 film Once Upon A Time In the West, Sergio Leone cast Henry Fonda as a vicious killer, an unredeemed bad man. It had a certain shock value, but it didn’t upend the moral dynamic of a traditional Western — we weren’t asked to root for the Fonda character, though we may have wanted to, given Fonda’s status as an iconic movie hero. This created an interesting tension.

In The Wild Bunch, Peckinpah took things further. His main protagonist was William Holden, another iconic movie hero, playing Pike Bishop, the leader of a gang of outlaws. In the first scene of the film, the gang is robbing a railroad office. A couple of hapless clerks and a woman are caught inside the office. Bishop says to his men, gesturing to the clerks and the woman, “If they move, kill them.”

This is roughly equivalent to Fonda killing a child at the beginning of Once Upon A Time In the West — it has the same shock value — but the similarity ends there. In The Wild Bunch as it unfolds we are asked to root for the Holden character, to admire him, a man who would murder an unarmed woman to commit a robbery. To me, this takes us into the territory of moral nihilism.

Bishop is cool, with the bearing and the aura of an iconic Western hero. He’s brave and competent, and loyal to his fellow outlaws. His willingness to murder innocent unarmed people is treated as morally meaningless. It’s something a hero can do if he wants to or needs to and still be a hero.

In a traditional Western, even a dark modern one like Clint Eastwood’s Unforgiven, we would expect a vicious killer like Bishop to have a change of heart, to recognize his own moral nullity, to be given a chance to redeem himself. But neither Bishop nor Peckinpah sees any need for redemption. Bishop’s style and will and bravery are redemption enough.

There are, as I say, arguments against this view — centering on the idea that Bishop and his gang, when they flee into Mexico, are touched by the goodness of the Mexican peasants and eventually sacrifice themselves in the cause of the peasants’ revolt against their corrupt government. I myself don’t see evidence for this in the text.

They certainly sympathize with the peasants and are disgusted by the corruption and viciousness of their oppressors, but they don’t think twice when the vicious and corrupt Federal general Mapache hires them to rob a U. S. Army train of the weapons it’s carrying, back on American soil, and deliver the weapons to him. They’re completely fine with killing American soldiers to accomplish the robbery.

It’s true that they agree to given Angel, a Mexican member of the gang, a case of rifles to pass along to the insurgent peasants, but only in return for his share of Mapache’s money. The wild bunch remain true to their nature — a gang of moral monsters, who will do just about anything, even the right thing, for money.

Bishop is not shown actually murdering an unarmed women, but in the opening he leaves the clerks and the woman in the railroad office as hostages in the charge of a psychotic gang member who does kill them when they move, trying to escape. They die off-screen — perhaps because Peckinpah doesn’t want to show us the graphic consequence of Pike’s repellent indifference to innocent human life.

Angel is shown murdering an unarmed woman, a former lover he kills because she has betrayed him and taken up with Mapache. There is no sign that any of the wild bunch has any moral qualms about this atrocious act. Quite the opposite in fact. At the climax of the film the gang sacrifices itself in an effort to rescue Angel from the Federales — a hopeless gesture which they know won’t succeed. In essence, they commit “suicide by Federales”, preferring to go down fighting rather than endure the fact that their era on the frontier is coming to an end.

Their suicide walk is justly famous — it’s designed to portray the outlaws as heroic, even though there’s nothing heroic about what they’re doing. Attempting to rescue “one of their own” is just a pretext for going out in a blaze of cosmetic glory. It’s no more heroic than the 9/11 terrorists flying planes into The Twin Towers — sacrificing their lives “bravely”, perhaps, but in the service of an ignoble cause.

Peckinpah can’t even allow the bunch to commit suicide honorably — at one point in the climactic shootout Dutch saves himself temporarily by using an unarmed woman as a human shield. She takes a bullet meant for him. The perversity of this is extreme. You get a feeling Peckinpah was expressing a deep contempt for the audience, mocking it as he was mocking the Western genre itself, because he could get it to root for such vile “heroes” as these.

I’ve read a “feminist” defense of Angel’s murder of his former lover, seeing it as a blow against the corrupt government that’s oppressing his people, a political act, motivated by Angel’s own self-hatred over his impotence in the face of that oppression. This is plausible psychologically, but it avoids the moral issue of murdering unarmed people, which doesn’t seem to interest Peckinpah at all, any more than it interests Bishop.

Understanding Angel’s act, even sympathizing with it, is not an excuse for utterly ignoring the moral questions it raises — again, on a par with understanding the motivations of the 9/11 terrorists while totally ignoring the moral questions raised by their act of murdering unarmed people.

I’m not saying that Peckinpah had an obligation as an artist to condemn Angel — only that ignoring the full moral dimensions of Angel’s act, in effect trivializing them, is an exercise in nihilism. In The Wild Bunch in general we are asked to cheer for some truly despicable men, to ignore their despicable acts, to revere them for their style and courage alone. It’s a shabby, puerile view of the world, and makes for a shabby, puerile film.

Peckinpah was a more complicated artist than The Wild Bunch would indicate. He loved showing the dark side of human nature without mitigation or pious revulsion, but he rarely presented that dark side as something to be laughed about, relished, celebrated as heroic. His own dark side led him into a life of creeping, harrowing despair — he knew only too well the price of a dalliance with moral nihilism, and that knowledge informs his best work, gives it depth and complexity. It’s entirely absent from The Wild Bunch.

So in the end, after revisiting the film with as open a mind as I could summon, I find that I still dislike The Wild Bunch intensely — for much the same reasons I outlined in an earlier post here. The film traffics in images of heroism, albeit stirring images of heroism, that are cheap and hollow and repulsive.