Monthly Archives: July 2014

VICTOR FLEMING: AN AMERICAN MOVIE MASTER

The director Victor Fleming was what used to be called a man’s man, back when such people existed in Hollywood. A hunter and a fisherman, he loved flying planes, skippering boats and tearing around on motorcycles. Dashing and handsome, outwardly gruff but unabashedly sentimental, too, he was known for exceptional gallantry towards the many women who fell for him and became his lovers, including Clara Bow and Ingrid Bergman.

He wasn’t, however, “a man’s director”, as some have argued. He had great rapport with Douglas Fairbanks and Clark Gable and Spencer Tracy, who liked to think of themselves as regular guys, too, but he guided Bow and Judy Garland and Vivian Leigh through some of the best performances by female actors ever recorded on film.

He made first-rate films in many different genres, which has affected his reputation as an auteur, but he was much more than a journeyman. In 1939, he pulled off what may be the most impressive feat of any director in history, “saving” over the course of that one year two of the best movies ever made, both of which were productions in serious trouble when he arrived to take them in hand — The Wizard Of Oz and Gone With the Wind.

Both were unusually collaborative projects, “created” by vast numbers of brilliant people who concocted the ingredients that made their magic possible — but it’s hard to imagine any other director who could have organized those ingredients as Fleming did, infused them with the momentum, complexity and feeling that make them great.

Fleming did it by his combination of strength, sensitivity and mastery of his craft. He brought out the child in Garland, who was anything but a child when she ventured into Oz. He brought out the larger-than-life vulgarity in Leigh, who wanted to play Scarlett as a grand and great lady, a creature of the drawing room rather than the center of a sprawling epic. He got Clark Gable to cry, in violation of Gable’s strongest instincts about how his star persona had to behave on screen.

Fleming imbued both those films with humanity and emotion without any cheap appeals to the heartstrings. He gave them pace and nuance. He made them classics, which play as well today as they ever did.

Michael Sragow’s wonderful new biography of Fleming gives the director his due without romanticizing the man or making greater claims for his artistry than his work can sustain, great as though claims may be.

Almost everyone agrees that The Wizard Of Oz and Gone With the Wind rank among the greatest glories of the Hollywood studio system. Hardly anyone thinks of their director as a major artist. Sragow’s book tries to resolve that paradox.

Ironically, it’s a paradox that probably wouldn’t have bothered Fleming. Being known as a fine and reliable director of commercial fare, having a reputation as a singular artist, were only important to him as levers he could use to get his way as a filmmaker, among the studio brass and on the set, where it mattered. Otherwise, he did his work, then went home and lived his life.

He just happened to do some of the best work ever done in the history of cinema.

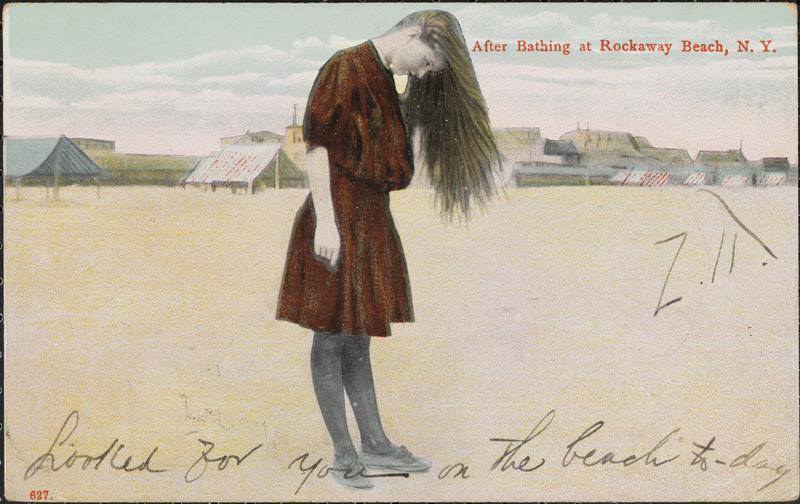

LOOKED FOR YOU ON THE BEACH TO-DAY

AN E. F. WARD FOR TODAY

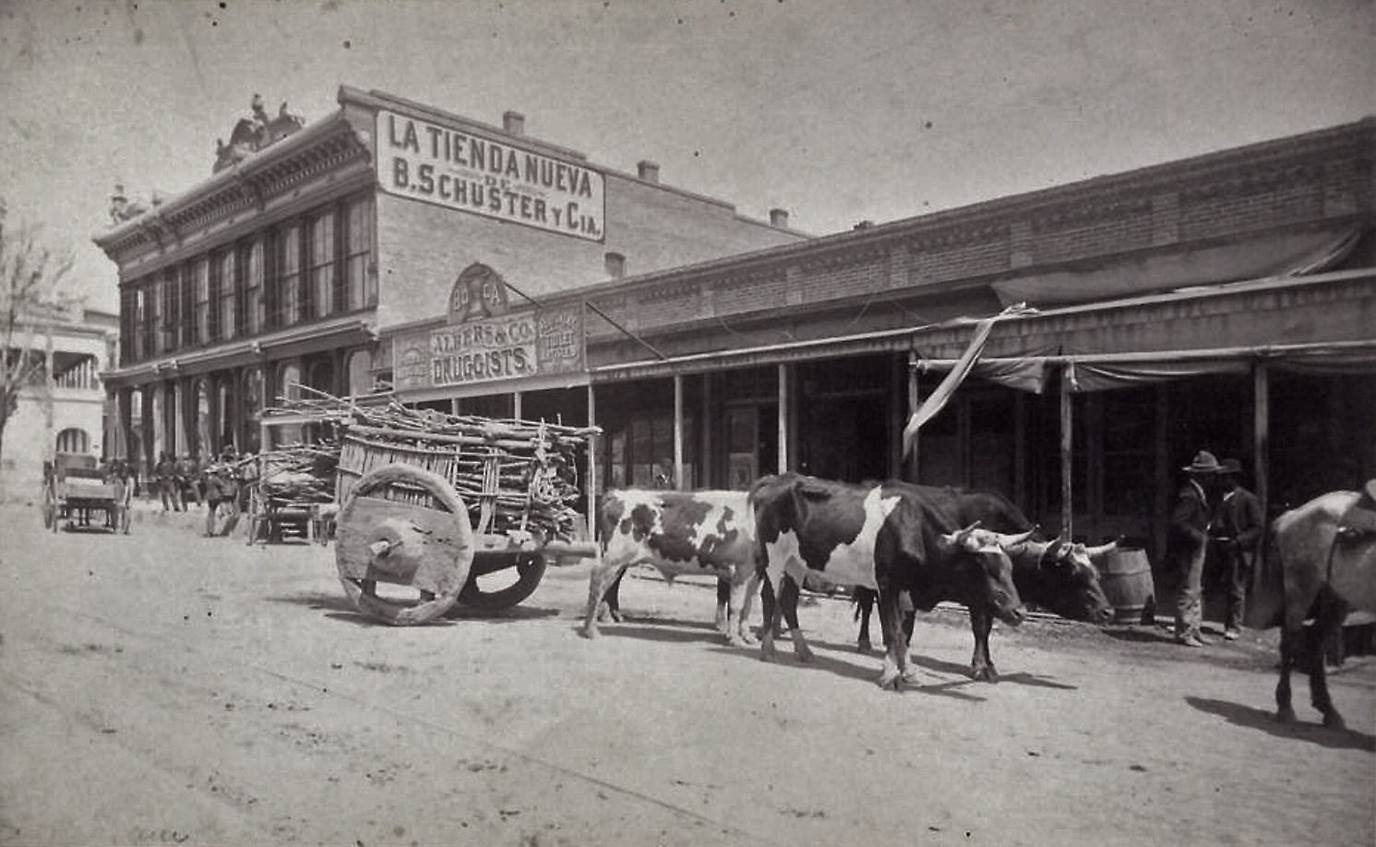

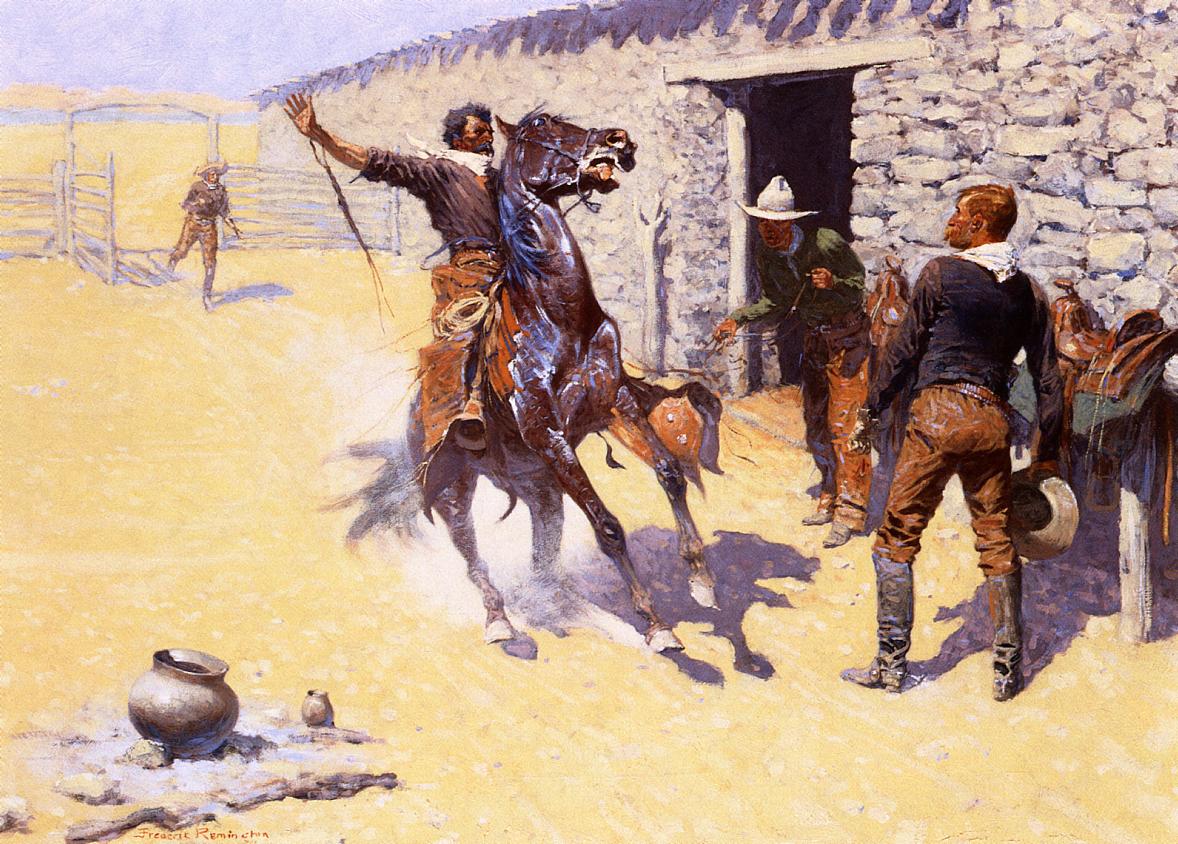

DOWN IN THE WEST TEXAS TOWN OF EL PASO

CATHY O’DONNELL

LEAVING CHEYENNE

I just saddled Old Paint and rode out of Facebook. I’d hung around that place for nearly five years and liked it well enough, made some good friends there, told my share of tall tales in the Silver Status Saloon — made a fool of myself there, too, from time to time but no one seemed to care too much.

Can’t say why I took a notion to ride off from the place — just an idea, I guess, that there might be better country further west, and that I might profit from some time on the move with less company around me. I felt good seeing the trail up ahead wind off into the distance, like a weight had been lifted off me, and bad thinking of sleeping out in the rain under a slicker on stormy nights, with none of the old crowd at the Silver Status around to stand me a glass.

If anybody asks about me back in town, someone is sure to say, “Oh, he was last seen heading off in the general direction of Montana.” I might go there, or I might go somewhere else.

AN LP COVER FOR TODAY

THE APACHES!

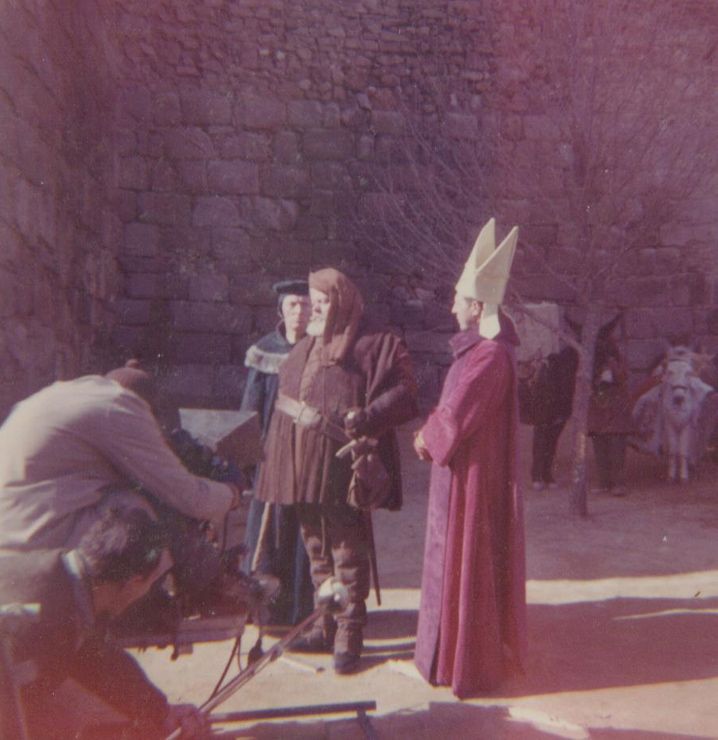

ON THE SET

DEMETRIUS AND THE GLADIATORS

In this rather lackluster sequel to The Robe Victor Mature reprises his role in the earlier film as the faithful ex-slave who recovers Jesus’s robe from the foot of the cross and carries it to Rome. In this film he’s in love with Lina, a chaste Christian girl, played by Debra Paget, but separated from her when he assaults a Roman soldier in her defense and is sent to gladiator school.

There, because he’s such a super hunk, he catches the eye of the lascivious Messalina, wife of Claudius, the Emperor Caligula’s uncle. She contrives ways to save his life and throws herself at him sexually. Messalina is played by Susan Hayward, and she is smoking hot in the film. In fact, she gives the picture the only juice it has.

The scenes of gladiatorial combat are clumsily staged, the Christian characters are all drips, and Jay Robinson’s Caligula is such a camp caricature of the mad emperor that he can’t be taken seriously as a villain, though the performance is certainly amusing.

Paget’s Lina is so thoroughly insipid that your heart leaps up when Demetrius loses his faith and decides to commit adultery with Messalina, which sort of subverts the film’s nominal allegiance to Christian virtue. By the same token, when Demetrius gets his faith back and stops boffing Messalina, the picture is essentially over.

The film, like The Robe before it, was a smash hit, but it’s hard to imagine why. The novelty of Cinemascope, in 1954, and Hayward’s carnality must have carried the day with audiences of the time.

Click on the images to enlarge.

A COMIC BOOK COVER FOR TODAY

A WESTERN MOVIE POSTER FOR TODAY

A PAPERBACK COVER FOR TODAY

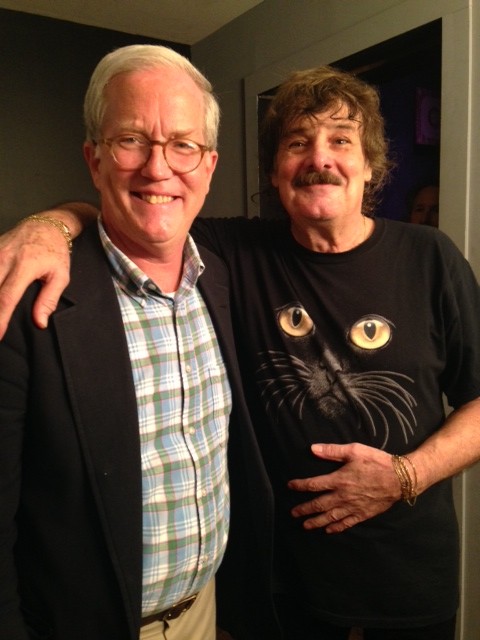

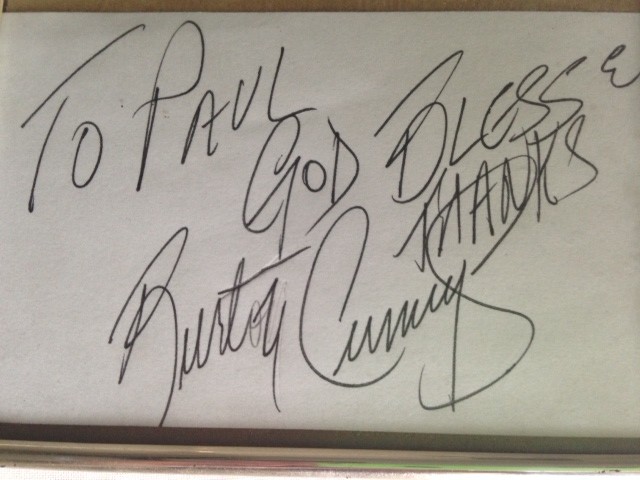

THE PASTOR AND THE POP STAR

PZ goes to see one of his favorite pop stars in concert, becomes a part of the event and writes about it below:

TAKE COURAGE — HE IS CALLING YOU

In the Bible a blind man calls persistently on the Lord to be healed. He finally gets the message back: “Take courage. He is calling you.” A good thing then happens.

I felt like the blind man recently, when someone I admire decided he wanted to see me.

Burton Cummings, who became famous long ago as lead singer and keyboard player of The Guess Who and later launched a solo career, is a rare artist who seems to me almost completely unfiltered. What I mean is, he rarely filters his emotions. His songs are full of unfiltered feeling — so much so that they are sometimes too hot to handle. Songs like “These Eyes”, “Stand Tall”, and “Sour Suite” are hard on the listener yet massively cathartic.

“I’m Scared” made a special impression on me, because it tells the story of Cummings’s spiritual epiphany that he had while sheltering from the cold one day in St. Thomas Episcopal Church at 53rd and Fifth in Manhattan (above). Something happened that day, and the song is still one of his most popular, if not the most popular of anything he’s ever written.

Well, last week, at my wife’s suggestion, I went to see Burton Cummings at the City Winery on Varick Street in Soho. When I arrived, in the middle of a thunderstorm, I passed in a note, hoping against hope, to a member of Cummings’s team, that an Episcopal minister was there tonight who had an association with what the song “I’m Scared” refers to as “the Cathedral of St. Thomas”. (I’ve preached there several times over the years, and led forums there, and been good friends with two long-term rectors of the parish.)

Then suddenly, in his intro to “I’m Scared”, Burton Cummings said that he understood “there is a pastor in the audience tonight” to whom he wished to dedicate the song. He asked where I was sitting, and the teenager sitting two seats away from me, shouted, “He’s here! He’s over here!” I couldn’t believe it.

Then, at the end of the show, he announced that he wanted to see me as soon as possible.

Like the blind beggar in the Old Story, I went forward. Cummings’s manager, Lorne Saifer, took me by the elbow straight into the inner sanctum. There, literally bathed in light — for Cummings’s videographer, Lil Sarafian, was filming our meeting — was the man himself.

What transpired was so lovely and so dear, and so personal, that I can barely believe it happened. We spoke for ten minutes about Cummings’s spiritual beliefs; what the song “I’m Scared” had meant to his mother, who died two years ago; and what he thinks about religion today and its purpose. He told me he had grown up in the Anglican Church of Canada, and when I mentioned that St. Thomas is an Episcopal (i.e., Anglican) church, he said, “Oh, you see! I thought it was Presbyterian!”

Then the seer put his arm around me and called for a photo. He gripped my hands in both of his, and in the most heartfelt possible way, thanked me for coming. He thanked me — as if.

The manager escorted me out and twinkled, “You see, pastor, prayers are answered.”

Well, that’s it. Not only are the songs of Burton Cummings the very instance of unfiltered emotion in music, but our “splendid combination” (Gene Chandler) that night was unfiltered, too. Something passed between us. To quote Cummings again, “I thought that stuff was invisible.”