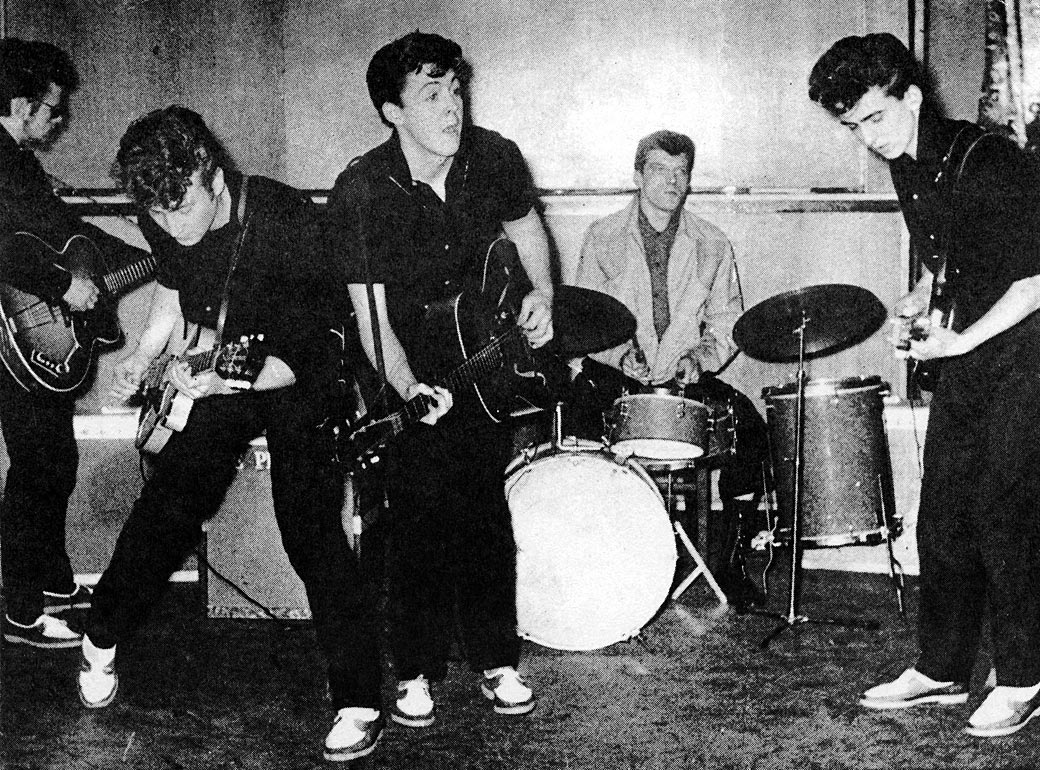

John, Paul, George and Ringo recorded as The Beatles for seven years, producing 214 tracks. Almost everything they created together was magical, expertly crafted, joyful, sublime in simple and sometimes not so simple ways.

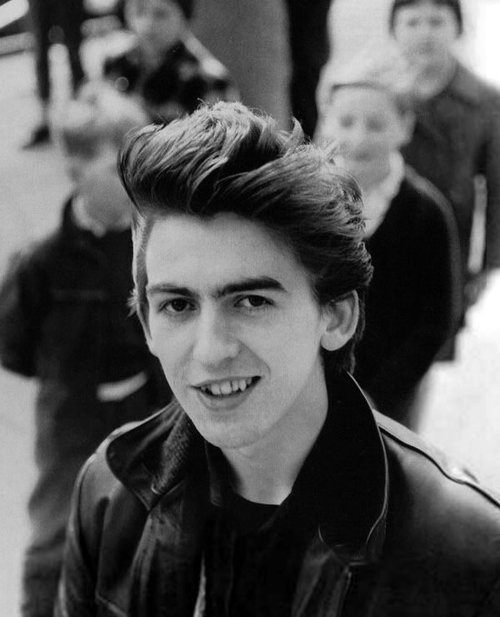

And then The Beatles were over, the peculiar phenomenon called The Beatles was over. Beatlemania, which never really went away while the lads were turning out new work, changed into something else — Beatles obsessiveness. As John, Paul, George and Ringo worked to define themselves as individual artists, sometimes collaborating with each other, sometimes squabbling about the past, manic Beatles fans began dissecting their music, collecting studio outtakes, writing volume after volume about the work and the career of The Beatles.

The impulse was clear — finding something new or generally unknown about The Beatles was a way of warding off the truth that there would probably never be any new Beatles music.

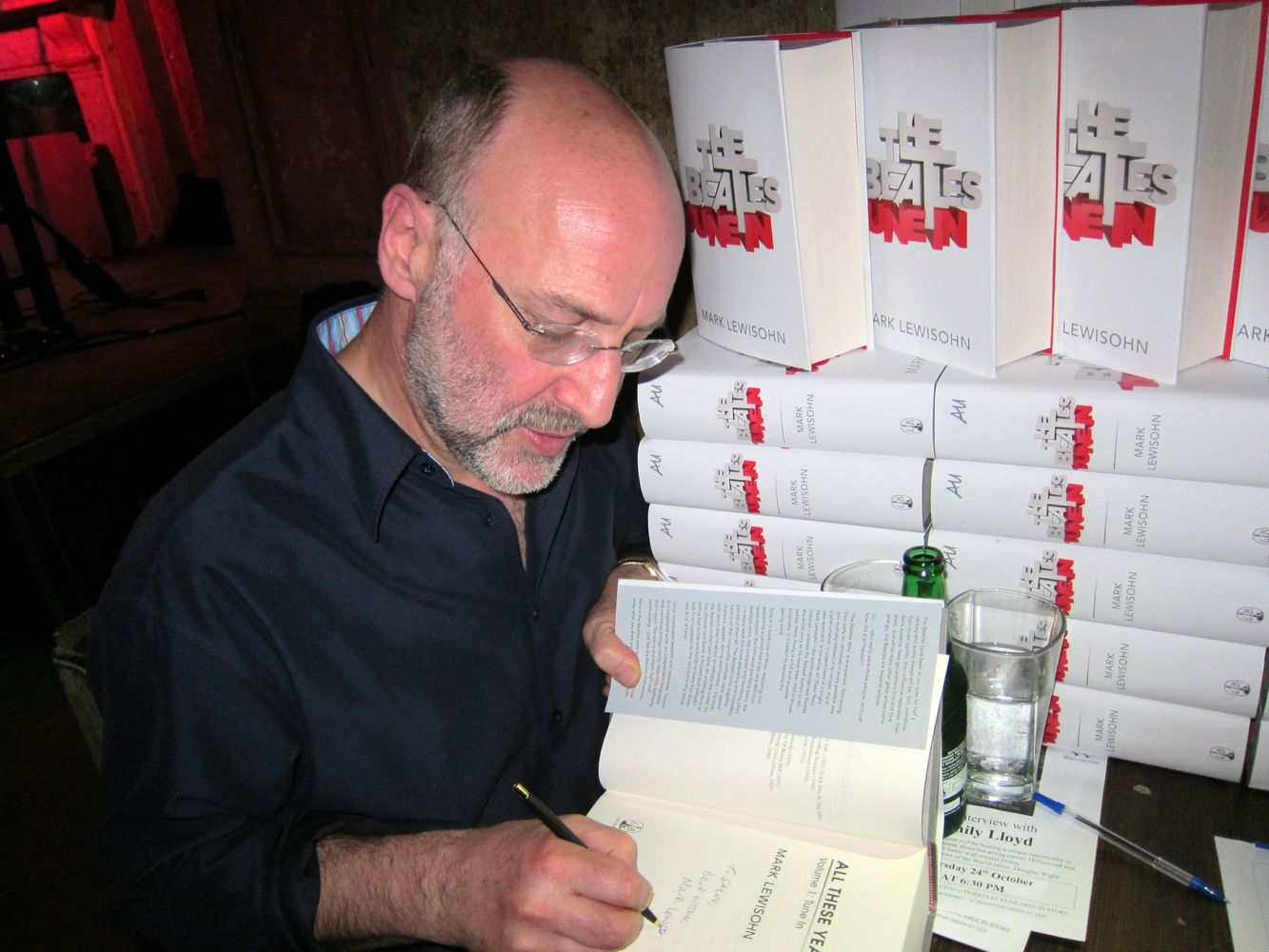

Mark Lewisohn’s magnum opus about The Beatles, All These Years, of which the first volume, Tune In, has just been published, is the ultimate expression of Beatles obsession. It aims to put between covers every fact that’s known, every fact that probably can be known, about The Beatles.

Tune In is available in two editions, the regular trade edition, which comes in at just under a thousand pages, and an “extended edition”, in two volumes, of over 1700 pages (at this point only available in the UK.) It follows the lives and careers of John, Paul, George and Ringo (and George Martin and Brian Epstein) — as well as the state of the trans-Atlantic music business — until 1962, when The Beatles had their spectacular commercial break-out.

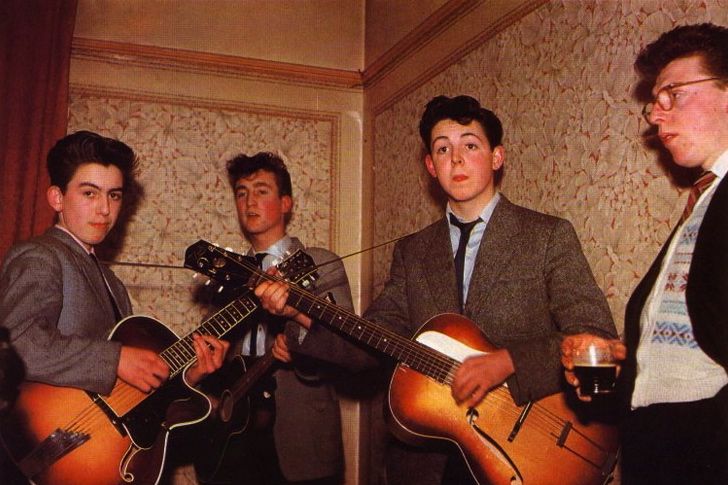

The detail in the extended edition I’m reading is staggering — it’s like entering a parallel universe made up entirely of facts about or relating to The Beatles. You and I don’t know or remember as much about our own families and lives as Lewisohn has unearthed and set down about the families and lives of The Beatles. It would be a fascinating exercise in fanatical exhaustiveness even if it weren’t about four extraordinary artists.

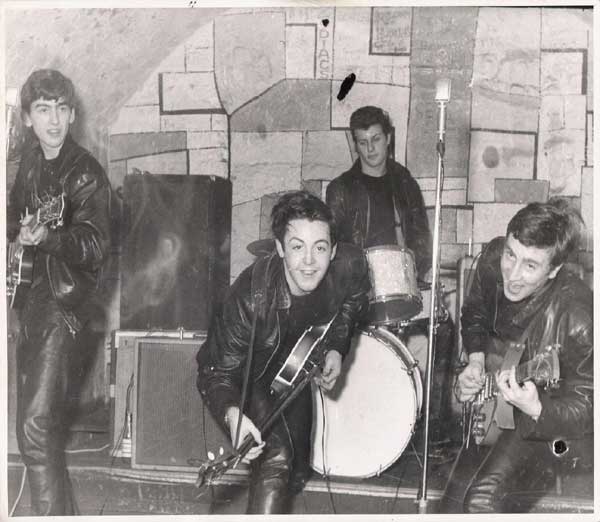

Lewisohn’s style is chatty and readable, if not particularly elegant, his method meticulous to a mad degree — if you want to know the exact street address of the strip club in Liverpool where the lads briefly played before they made it big and the precise layout of the club, you’ll find it here.

Call it overkill, call it an epic love song to their work — whatever you call it, it’s amazing. It brings the group to life again in the only way it can be brought to life again, except in the recordings themselves — by telling us things we never knew about the lads, about the creation of their music, and by putting us back in touch with the times they inhabited and changed, for many of us the times of our own youth.

If you love The Beatles you’ll love the book, but it will also make you sad. This is the last word on the group — a long, loving, dazzling last word. From now on, only the music will have anything new to tell us, but fortunately it will keep on doing that forever.