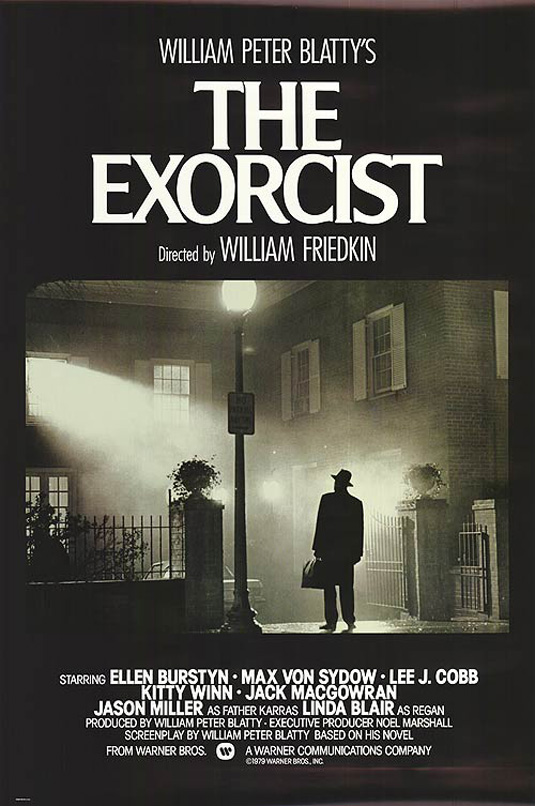

William Friedkin’s The Exorcist is a hard film to write about. It doesn’t lend itself to any sort of aesthetic analysis because it makes no appeal to our aesthetic sensibilities. There is only one image in the film which has any kind of aesthetic beauty or power — the shot of Father Merrin arriving at the McNeil house at night in a light fog, adapted for use on the poster. (The image was inspired by a painting by René Magritte.)

There is tremendous craft at work in the film but it might best be described as ruthlessly utilitarian — all of it is designed to unsettle the viewer, to induce a sense of creeping dread, and it does this with irresistible efficiency.

Friedkin has spoken of wanting to give a documentary feel to the look of the film but that’s not quite what he does. The film is carefully lit and mixes artfully composed shots, including tracking shots, with zooms — a mix not normally found in documentaries.

The main effort of the cinematography is to resist glamorizing the settings or the actors — to present them neutrally. Dark scenes and light scenes alternate regularly, to keep the viewer off balance, but the dark scenes are not atmospheric in an expressive way — they’re just set in dark places. (Quiet scenes similarly alternate with loud scenes in the precisely modulated soundtrack.)

The acting, which is uniformly fine, also resists glamorizing any of the characters — its aim is to convey psychologically convincing reactions to extreme and increasingly fantastic events.

You would never fantasize about being any of the characters — you wouldn’t even relish the prospect of spending time with them, with the possible exception of young Regan before and after her possession. And yet you are absolutely riveted by their ordeals, wracked with sympathy and fears for them. This is all extremely unusual for a Hollywood film.

The unease which the film evokes proceeds from everyday anxieties — rats in the attic, a mentally disturbed child, harrowing medical procedures, social humiliation — to supernatural horrors in such well-calculated stages that we are prepared to accept the horrors as mere magnifications, or manifestations, of the familiar anxieties.

It’s an absolutely brilliant exercise in audience manipulation, but the film deals with subjects of such substance and depth that it can’t be dismissed as cynical sensationalism for its own sake.

It’s a great film, but great in ways few other films are, willing to sacrifice artistry for impact, aesthetics for subliminal emotional effects. It’s still, 41 years on, one of the scariest movies ever made, and one of the most affecting.

Click on the images to enlarge.

Nice piece. I’m reading “Rosemary’s Baby” right now and was wondering if it was one of the inspirations for “The Omen” and “The Exorcist.” Instead of “What if a woman’s unborn child was Satan?” it’s easy to see other writers asking, “What if a young child was Satan? What if a teenage girl was?”

“The Exorcist” has a somewhat different theme than “Rosemary’s Baby” or “The Omen” — it’s not about Satan entering the world in human form but about Satan, or some demon, possessing a human being, through that human being’s vulnerability. It’s about possession rather than incarnation. This makes it much more affecting emotionally, to me, because the possessed child remains intact in its innocence and can still be rescued. It’s ultimately a film about divorce and the devastating, almost dehumanizing effects of divorce on a child.