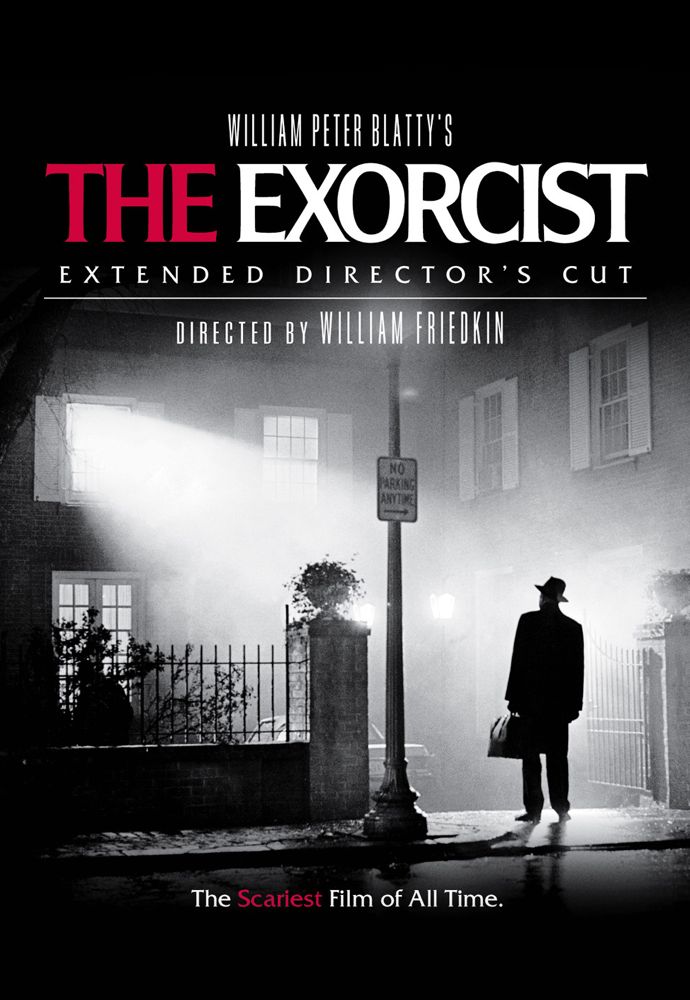

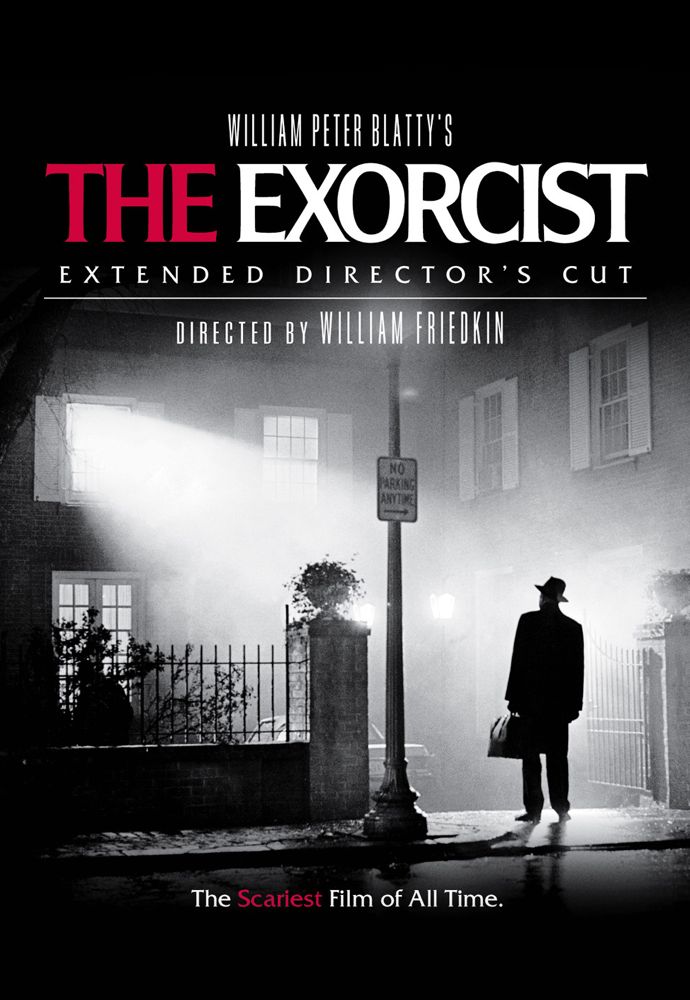

[Note: This analysis of the extended director’s cut of The Exorcist contains spoilers. If you haven’t seen the film you ought to do so immediately, but you should watch the original theatrical cut first, for reasons I outline below.]

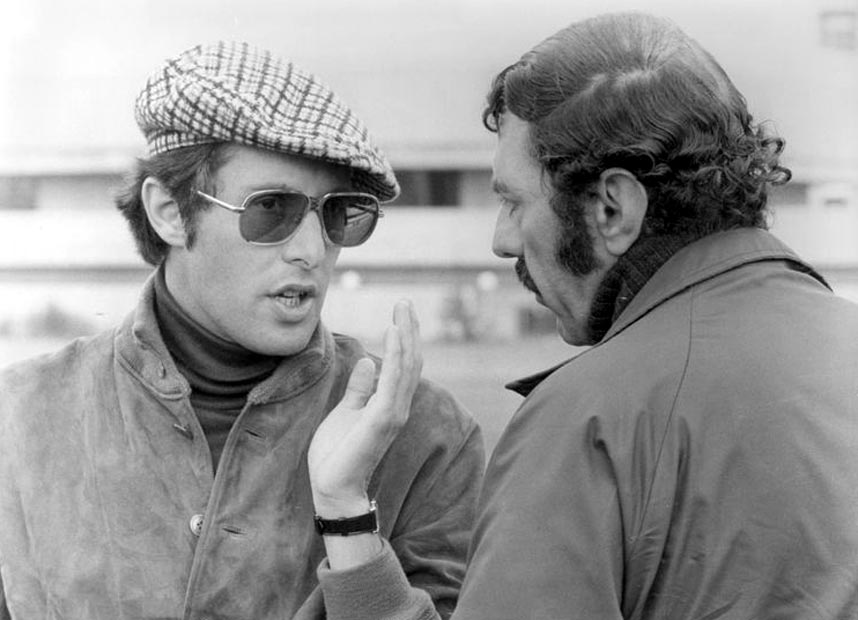

In 2000, William Friedkin (pictured below in that year with screenwriter William Peter Blatty) created an extended director’s cut of his 1973 film which restored several scenes eliminated from the original theatrical release, adding about twelve minutes to the running time of the film. All of the restorations, for various reasons, are unfortunate and seriously undermine the film’s power.

One of the greatest virtues of the original cut of The Exorcist was its pacing, moving by inexorable but largely subliminal degrees from ordinary anxieties and misfortunes into the realm of the supernatural. Friedkin’s calculation of this progress was impeccable in the original cut and tremendously effective.

In the original we sense — without being obviously alerted to — the tensions of the McNeil household, the psychological disturbance at work in young Regan as she tries to deal with her parents’ divorce. The depth of that disturbance doesn’t become alarming until Regan urinates on the carpet during the course of one of her mother’s parties.

It’s one of the most harrowing moments in the film because it combines the social distress of Regan’s mom and her guests with a graphic representation of the child’s emotional instability. It is followed by the first potentially supernatural event of the film — the violent and uncanny shaking of Regan’s bed.

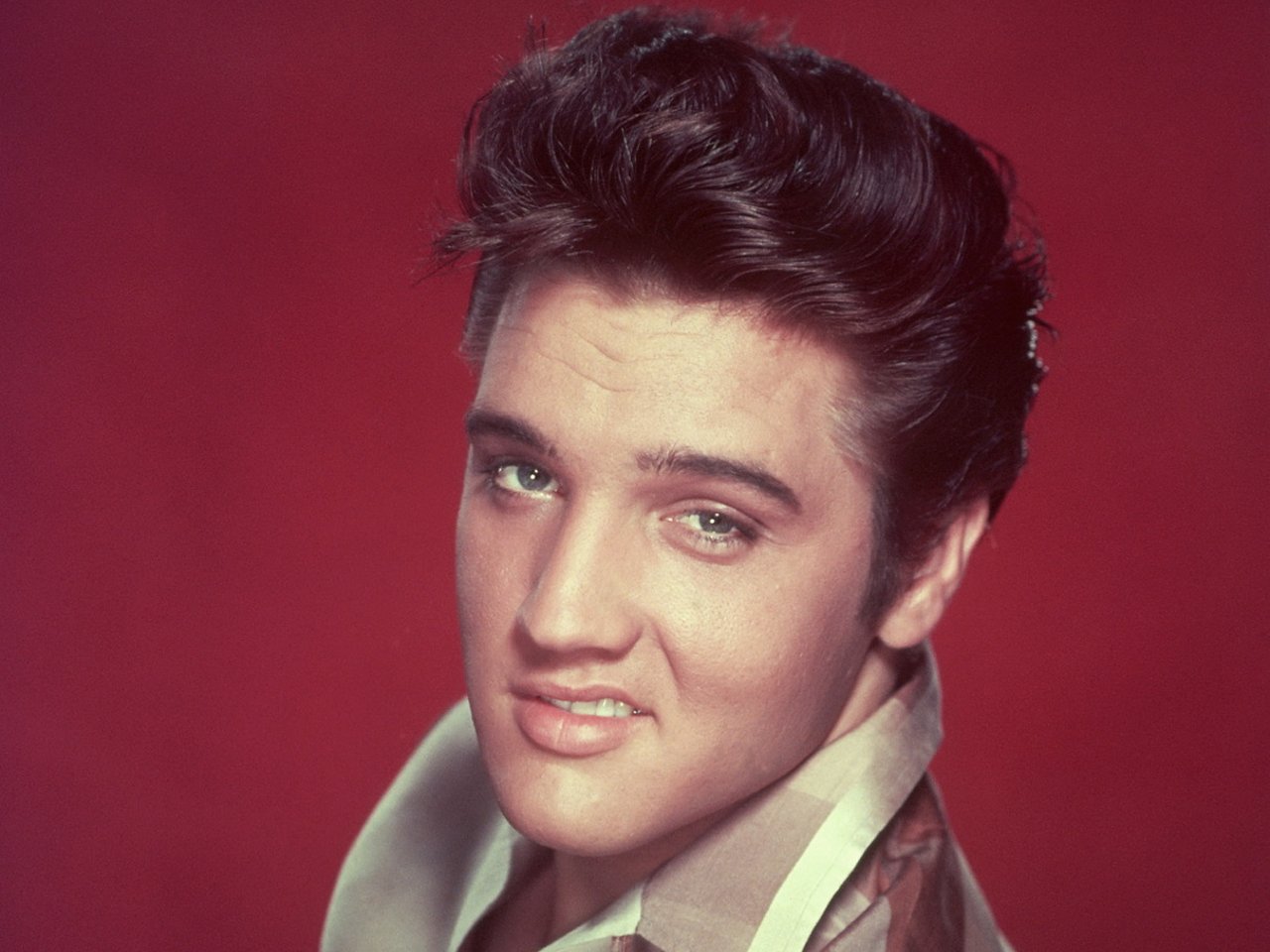

Friedkin, however, in his extended cut, has chosen to restore an earlier scene (above) of Regan being examined in a hospital, which reveals her developing neurosis more clearly and warns us how serious it might be or might become. This scene totally undercuts the urination episode, prepares us for it and lessens the shock of it.

At the same time the restored scene doesn’t tell us anything we haven’t already sensed about Regan’s state of mind, and as usual in a drama, especially in a horror film, what we sense tends to be far more powerful than what we are told.

Friedkin also restored a brief scene that was meant to follow the news of Burke Denning’s death. The moment Chris McNeil learns of this, Regan appears crawling upside down and backwards down the stairs, like a spider.

Friedkin originally cut the scene because the wires used to create the effect were visible on the stunt double who performed it, and this was in the days before such wires could be eliminated digitally.

It’s a potent and creepy image but it’s out of place at that moment in the film. In the first place, as Friedkin and Blatty once admitted in a filmed interview, it gives the scene a double climax, lessening the impact of the news of Denning’s demise.

More importantly it shifts our attention from the mystery of Denning’s death, a possible murder committed by Regan, to a graphic and undeniable demonstration of Regan’s demonic power. The murder mystery element, which soon involves the police investigator Lieutenant Kinderman, is a kind of diversion from the supernatural angle, and intriguing on its own. It seems like a too obvious red herring, however — pretty much irrelevant — in the wake of Regan’s spider crawl.

Friedkin restored a scene (above) in which Father Karras listens to a tape Regan made for her father before she became possessed. It gives Karras an appreciation of the normal child Regan once was, but it’s an appreciation we as the audience already have.

Reintroducing the absent father here also seems too on the nose. In many ways, The Exorcist is about the effects of divorce on a child, but this theme works best when it’s implied, when it plays on our emotions indirectly. If we are given too many chances to see Regan’s possession as a metaphor, it loses its power to engage our unconscious.

Our culture may intuit the destructive effects of divorce on children, but it’s not something we want to face up to — we want to see divorce as a rational and neutral way of dealing with a troubled marriage, which children experience as something to be expected in the normal course of things (which they never do.) We have to be tricked into contact with our darker intuitions about the subject — as in movies like The Sixth Sense, which is also a film about divorce masquerading as a horror film.

After father Merrin arrives at the McNeil home to begin the exorcism, Friedkin has restored two scenes of quiet before the ritual begins — a wry and warm exchange in which Chris McNeil gives Merrin some coffee laced with Brandy, and a briefer exchange (above) in which Merrin asks Chris what Regan’s middle name is.

Friedkin has said he thinks these scenes humanize Merrin, and perhaps they do, but they also undercut the impression Merrin gives of an implacable determination to confront the evil in the McNeil home at any cost and without any delay. These displays of courage and haste — because Merrin knows he hasn’t got many human resources left for the task at hand — are emblems of his heroism, and they lose some of their weight in the context of the restored scenes.

When Merrin and Karras take a break in the middle of the exorcism, Blatty had written, and Fiedkin had filmed, an exchange between them, in which Merrin proposes the idea that the target of the demon was never Regan, but the two priests, whose faith the demon hoped to undermine. Friedkin has restored this exchange (above) in his extended cut.

It conveys an interesting idea, and a valid interpretation of Regan’s possession, but it strikes me as too limiting. Surely Regan was not chosen at random — surely her vulnerability as a child of divorce is part of the meaning of the film. Spelling out one facet of that meaning undercuts others, unnecessarily in my view. A good story can resonate on many different levels, and in many different ways, for different viewers.

Blatty’s desire to instruct the audience on the tale’s meaning, to reduce it to one meaning, was misguided.

Finally, Friedkin has restored the original lighthearted coda Blatty included in his screenplay, when Father Dyer and Lieutenant Kinderman (above) start to strike up a friendship. Blatty said this was meant to reassure viewers that all was right with the world again in the wake of Regan’s salvation, but it rings false in the shadow of the great contest between good and evil we’ve just witnessed.

Are we really supposed to believe that this contest has ended with the rescue of one child? The very idea cheapens the thematic grandeur of the tale. We should walk out of The Exorcist in the grip of awe and dread, and perhaps a provisional exaltation — but certainly not with good humor and satisfaction.

I suspect that the observations above accord pretty closely with the thoughts and intuitions of Friedkin when he made his first cut of the film. They were the right thoughts and intuitions and he should have stuck by them.

A new director’s cut has commercial value, of course — it gives people a reason to buy yet another version of the film, and this one is certainly worth taking a look at. Friedkin has also confessed that he restored many of the cut scenes out of affection and respect for Blatty, who has always regretted their loss — and there’s something admirable about that.

Still, the original theatrical cut remains superior and definitive.