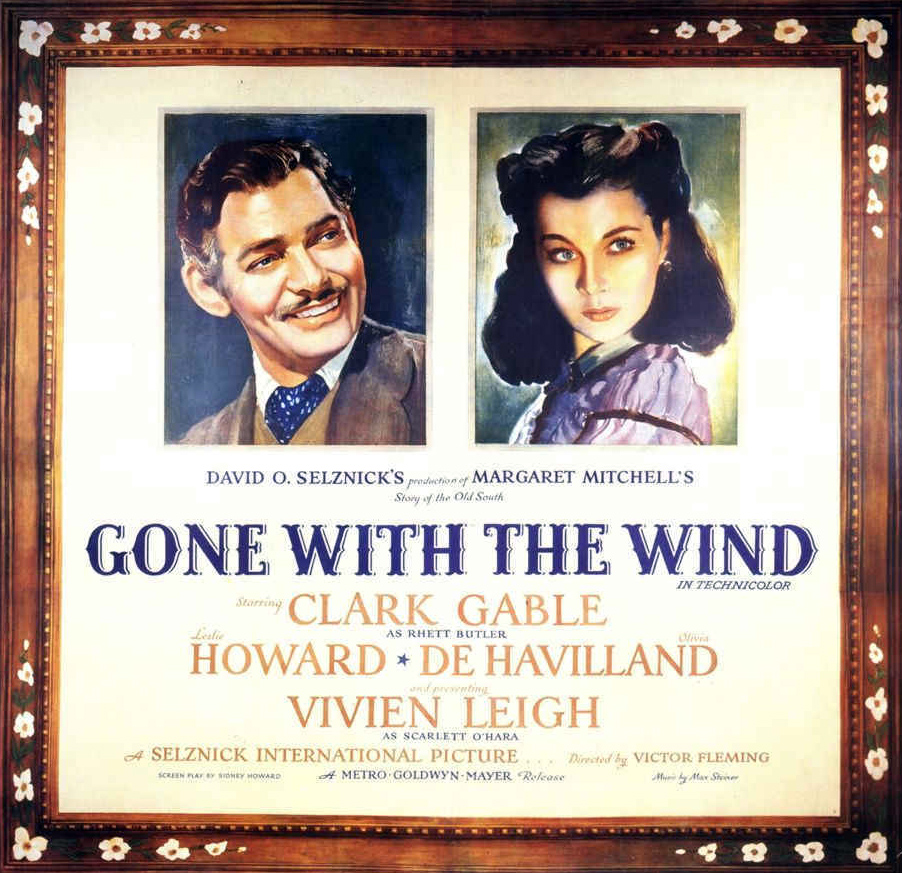

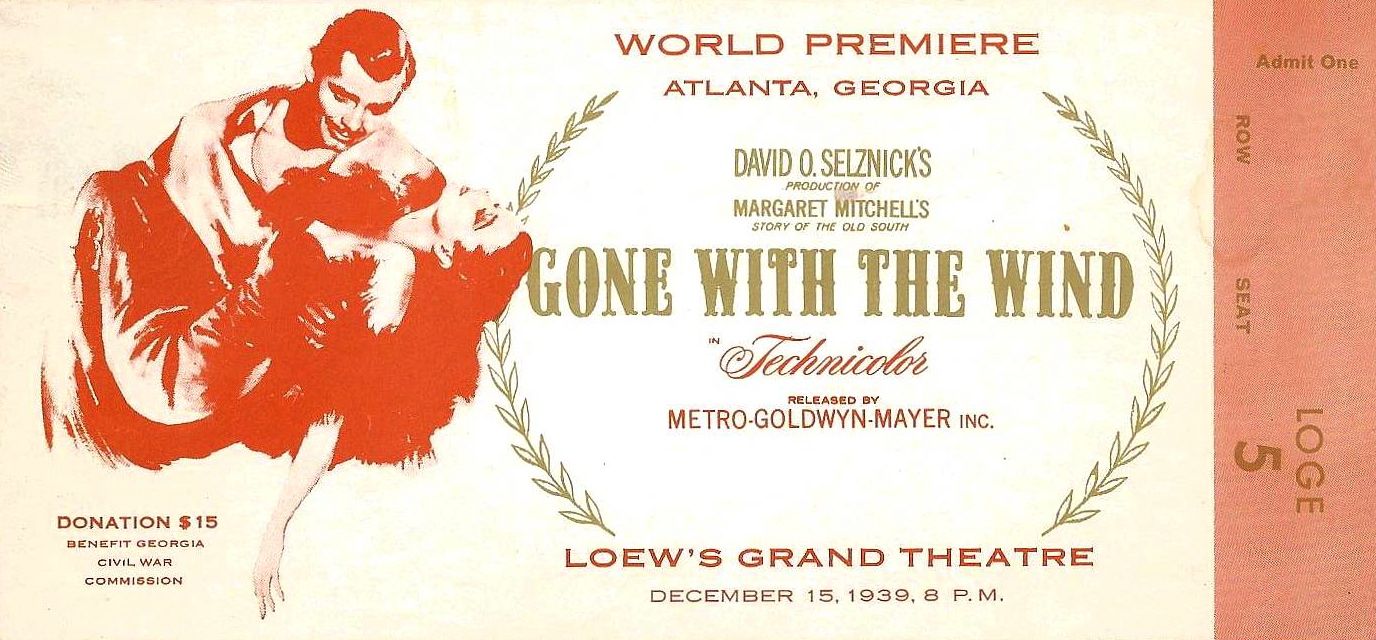

Gone With the Wind arrived in Wilmington, North Carolina on 26 February 1940. The whole world was abuzz about the film, which was already on its way to becoming the highest grossing movie of all time, in adjusted dollars. (The Birth Of A Nation may well have made more money but complete box office records for it have not survived, so we will never know.)

Nowhere was the buzz more intense than in the South, anxious to experience the romantic vision of antebellum Dixie that lived, however preposterously, in most Southern hearts. Young Southern women were going to see the notorious Scarlett O’Hara in action, courted by none other than Clark Gable, the screen’s premiere heart throb, as Rhett Butler.

An advance ad for the film in Wilmington’s The Morning Star read, “Wilmington and East Carolina Welcome Gone With the Wind With Open Arms!”

My mom (pictured today at the head of this post), who grew up in Wilmington, was 14 years-old at the time and she and some girlfriends had plans to go downtown to see the film on its opening day. It would not be like any other trip to the movies.

The film was playing at The Carolina, Wilmington’s premiere movie palace, located on the corner of Market Street and Second, just blocks from her father’s, my grandfather’s, men’s clothing store on Front Street. The Carolina had a marble-faced lobby and a whites-only policy — it was too classy to admit blacks, even in a special segregated section.

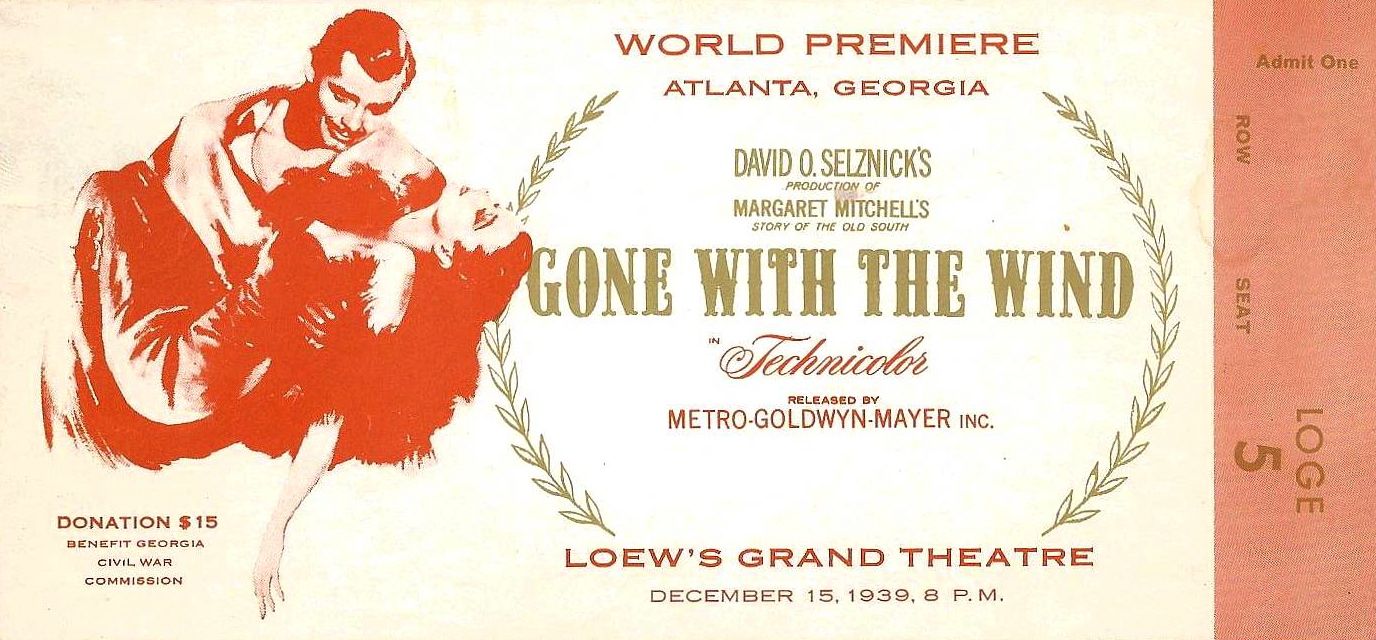

Gone With the Wind would be playing in a modified road-show presentation, carefully negotiated by the film’s producer and part-owner David O. Selznick and its distributor and part-owner MGM. There would be two “continuous run” showings per day, at 10am and 2pm, priced at 75 cents a ticket, three to five times the price for a regular movie. (Continuous run meant that you could go into the theater in the middle of the first show and sit through the first half of the second show — the seats weren’t reserved.)

At night it was reserved seating only, with tickets priced at $1.10. (These could be bought in advance at a furniture store downtown.) Because the movie ran nearly four hours, a transportation company had arranged for special buses to ply the regular city routes after hours, picking up patrons in front of the theater at 11:45 at the end of the 8pm show.

It was an event, a big event. My mom was beside herself with excitement about it. But the night before the opening, her father decided that he would not allow her to see the movie. He was a fairly strict Baptist, who would not permit card playing in the home on Sundays and did not approve of movies, even the grand Southern epic that was Gone With the Wind. My mom was devastated.

In her 80s she still remembered the moment vividly. “I went to sleep that night,” she told me, in hushed tones, “thinking I wasn’t going to see Gone With the Wind.” The dashed dreams of a 14 year-old girl are not small things, and they don’t grow smaller after a mere 70 years.

The next morning, however, her father had changed his mind — he relented and let her go see the movie with her friends, and she became one among millions enchanted by that marvel of popular art when it was brand new.

Her impressions of that first showing — she’s seen it several times since — are vague, but she always remembered that it had an intermission. An intermission!