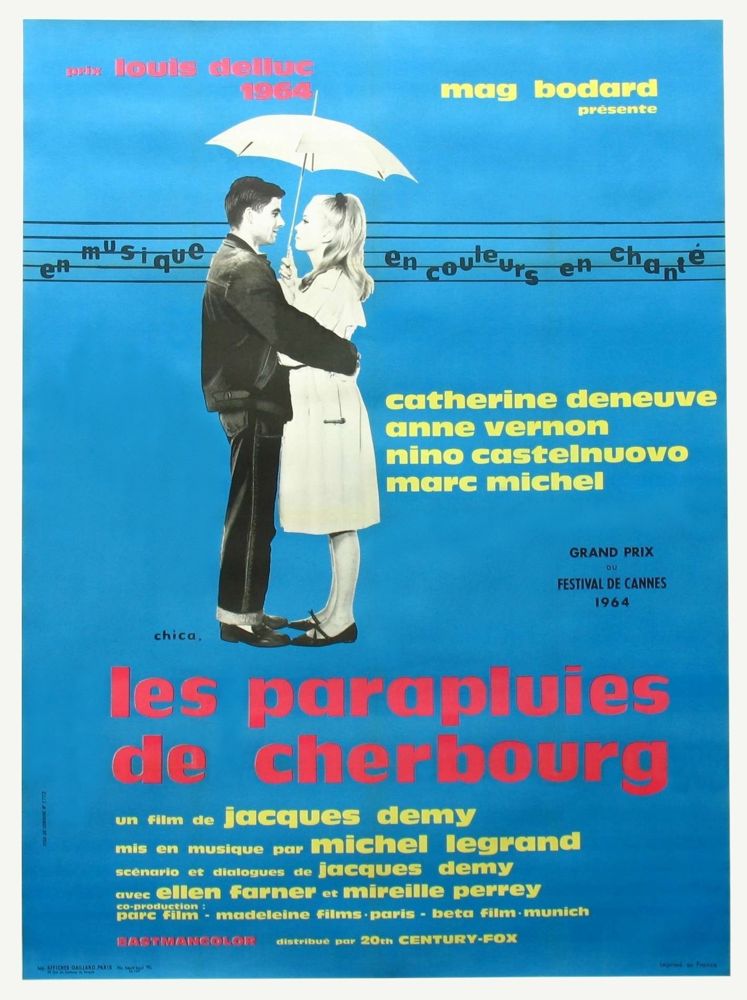

In 10th grade I entered a high school public speaking contest. I took it upon myself to compare and contrast two recent movie musicals — The Umbrellas Of Cherbourg and The Sound Of Music.

I was at the time a big fan of the French New Wave and almost completely immune to the genius of classic Hollywood musicals. Naturally I proved by unassailable logic that The Umbrellas Of Cherbourg was a masterpiece while The Sound Of Music was a bit of commercial fluff.

I just watched the two films again on Blu-ray. My thoughts about them . . . have evolved.

This may sound ridiculously obvious but when considering a musical it’s really important to consider its music. The music Richard Rodgers wrote for The Sound Of Music is, quite simply, beyond praise, beyond critical appraisal. Michel Legrand’s music for The Umbrellas Of Cherborg is also very fine, but not in the same league as Rodgers’s. Both serve the artistic ambitions of their respective movies with equal felicity and skill, but Rodgers’s score has a timeless brilliance that transcends its emotional or dramatic functions. He wrote melodies that have a life of their own, that are immortal.

Only one of Legrand’s melodies has something of that quality:

Still, there are half a dozen songs in the Sound Of Music in the same class, and no others in The Umbrellas Of Cherbourg. To be fair, The Umbrellas Of Cherbourg is not a musical structured around set-piece numbers. It’s all sung but most of it is jazzy recitative evoking normal spoken dialogue. What this means in practice, though, its that the great set-piece melody at the heart of the movie has to carry the whole emotional weight of the film, musically speaking.

There are no memorable melodies that provide contrast, that embody the various ancillary moods of the film — it’s either vernacular recitative or the grand lyrical passion of this one melody . . . ultimately a tenuous structure.

Demy’s lyrics for the recitative and for Legrand’s great central tune are purely functional dramatically. Oscar Hammerstein’s lyrics for the Rodgers tunes are exercises in virtuoso wordsmithing — bordering on the treacly in passages, perhaps, but mostly dazzling in their simplicity and ingenuity, a combination of qualities that only a poet of genius can pull off.

Hammerstein died soon after the premiere of the Broadway play. The last lyric he completed before he died was the one for this song:

What a way to go out, on an accomplishment of pure perfection.

In general, looking at the two movies today, I find that I’m better able to appreciate the uses of virtuosity, the emotional effectiveness of virtuosity, and the dramatic satisfactions of the traditional book-musical structure. By the same token, Robert Wise’s impeccable cinematic technique, rooted in Hollywood studio practice, seems as potent as Demy’s more personal and inventive style.

I still get choked up, as I did as a teenager, at the ending of The Umbrellas Of Cherbourg, but I get choked up more often throughout The Sound Of Music, at the simple sweetness conveyed by virtuoso technicians of the musical form, a sweetness conjured up without insistent aesthetic pretension.

As a teenager I used to think it was more important to be cool than to be kind — cool by my own quirky standards, perhaps, not by anyone else’s, but still . . . cool. Now I know that kindness is the greatest of all virtues, that without kindness, life has no meaning whatsoever, however cool you are or think you are.

I still think that The Umbrellas Of Cherbourg is a kind of masterpiece, but I now think that The Sound Of Music is a masterpiece, too, and in some ways a greater one. The Umbrellas Of Cherboug remains cooler than The Sound Of Music but it’s not a whit more powerful as a expression of life-changing human kindness.

One thing I didn’t appreciate as a teenager is the key thing the two films have in common — radiant and stupendous performances by their female leads, performances that don’t just redeem the films’ faults but obliterate them.

However saccharine The Sound Of Music is tempted to get, Julie Andrews’s English country-lass sexuality and music-hall good nature ground the film back in the real world. However arty and artificial The Umbrellas Of Cherbourg is tempted to get, Catherine Deneuve’s utter commitment to her role grounds the film back in authentic and persuasive emotion. Performances like those have a kind of music all their own.

[Note — when I say I get choked up by the ending of The Umbrellas Of Cherbourg what I mean is, not to put too fine a point on it, that I cry like a baby. By contrast, the idea that The Sound Of Music would also make me cry like a baby one day would have astonished my 16 year-old self. But I was so much older then — I’m younger than that now.]

we’ve been watching les desmoiselles de rochefort …

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Young_Girls_of_Rochefort

I love that movie. No great tunes in it, which keeps it out of the ranks of the great musicals, for me, but a great joy on every other level.