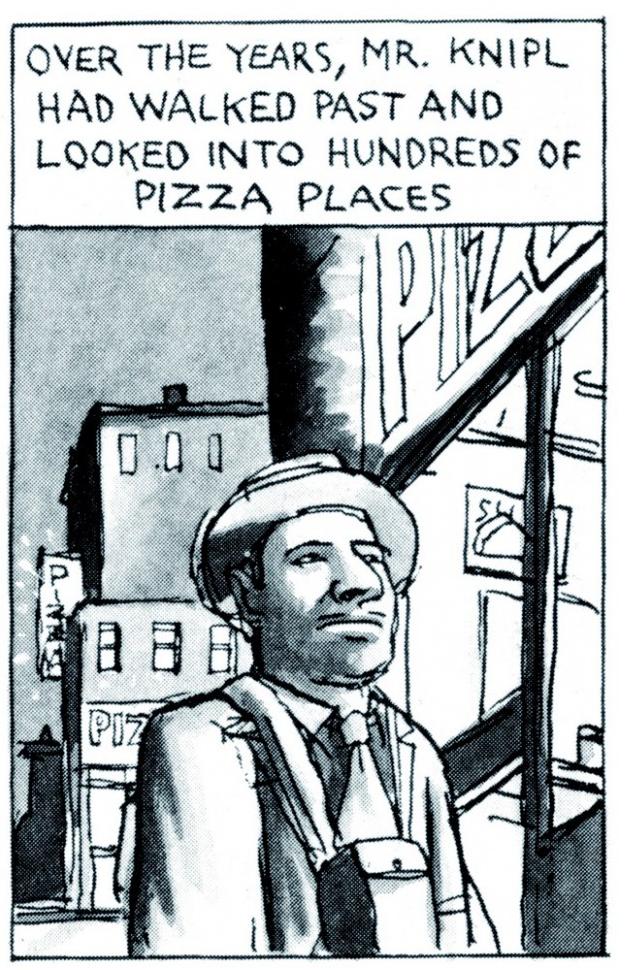

Ben Katchor is one of the truly great modern comic strip artists. He has a quirky drawing style, influenced a bit by the work of Ben Shahn, and quirky obsessions. Julius Knipl, Real Estate Photographer is a Katchor strip that appears in The Forward and other publications. Some of the strips are collected in The Beauty Supply District, a book I’m reading now.

They’re set in an imaginary New York that resembles sections of the real New York as it once was, vestiges of which remain — clusters of small-time manufacturers, retailers and wholesalers of modest industrial products and novelties.

When I first moved to New York in the 1970s I lived on a street in Chelsea which housed many such establishments — a maker of flags, a maker of coat-hangers, a maker of trophies. They’re all gone from my old neighborhood now, but they live on in Katchor’s strips, along with the eccentric salesmen who used to hawk such goods, the local cafes and delis that served the owners and employees of such firms.

They become in Katchor’s strips a kind of self-enclosed universe of desperate hustle and baffled ambition and weary resignation. It’s a universe that seems to know it’s doomed but carries on regardless. Today’s New Yorkers are dining in upscale restaurants that once housed cheap novelty display rooms, living in wildly expensive lofts where flags were once sewn. Katchor’s world is populated by the characters whose ghosts must still haunt such places.

It’s hard for me to believe that Manhattan once had large sections that were working class.

My impression is that the people who owned or worked in these small-scale establishments lived in the outer boroughs and commuted to work in Manhattan — at least by the time I moved to the city. But such establishments certainly proliferated in my old neighborhood.

You can look to the Corleone family for a pattern. They kept the storefront premises in Manhattan, the center of commerce, even as the family fortunes enabled them to flee the tenements for grander digs on Long Island. The guy that owned the building that housed my first loft, and still ran a one-man carpentry shop on the first floor, lived in Queens.

Watch Jules Dassin’s film Naked City, shot on location in New York in the late 1940s. Visit the Tenement Museum on the Lower East Side. Manhattan had working class people living there probably until the 1960s or ’70s.

For sure. It was a real city, once upon a time.

I share your esteem for the funnies, especially “Krazy Kat” and all things Herriman. I assume you know Gilbert Seldes’s “The Seven Lively Arts” (1924), which makes a case for comics as an art form and has a whole chapter devoted to Krazy, “The Krazy Kat That Walks by Himself.” He called the strip “”the most amusing and fantastic and satisfactory work of art produced in America today.”

I’m a big fan of “Krazy Kat” and am working my way through the many collections of the strip now in print. It’s consistently enchanting.

I think that strip may be unmatched for its linguistic richness–the “black cat” hipster talk, Yiddishe inflections and idioms, and sui generis lingo. Herriman was, as I recall, from New Orleans and of Creole descent, listed as “colored” in official paperwork. There are so many joys in “Krazy Kat,”starting with the love triangle–Krazy, Offissa Pup, Ignatz (dog loves cat and hates mouse, cat loves mouse, mouse is up to no good) and ending nowhere. There is plenty to engage intellectuals here and plenty to love. Much is visual: the unstable landscape rolling by, the adorable characters. Krazy’s red bowtie The black cat has long associations with anarchy. Ignatz is a German name, a version of Ignatius. Is Krazy Kat a boy or a girl? I think it was e.e. cummings who consistently called Krazy “she” but insisted she was really closer to a penguin or a meatloaf in appearance. I recently found an animated cartoon from 1916! It is just swell.

Shux! I forgot the orthography, dollink. An animated Krazy cartoon from 1916 doesn’t credit Herriman. But the spelling is pure Kat.

Oops. The animated cartoon does credit Herriman, big time.