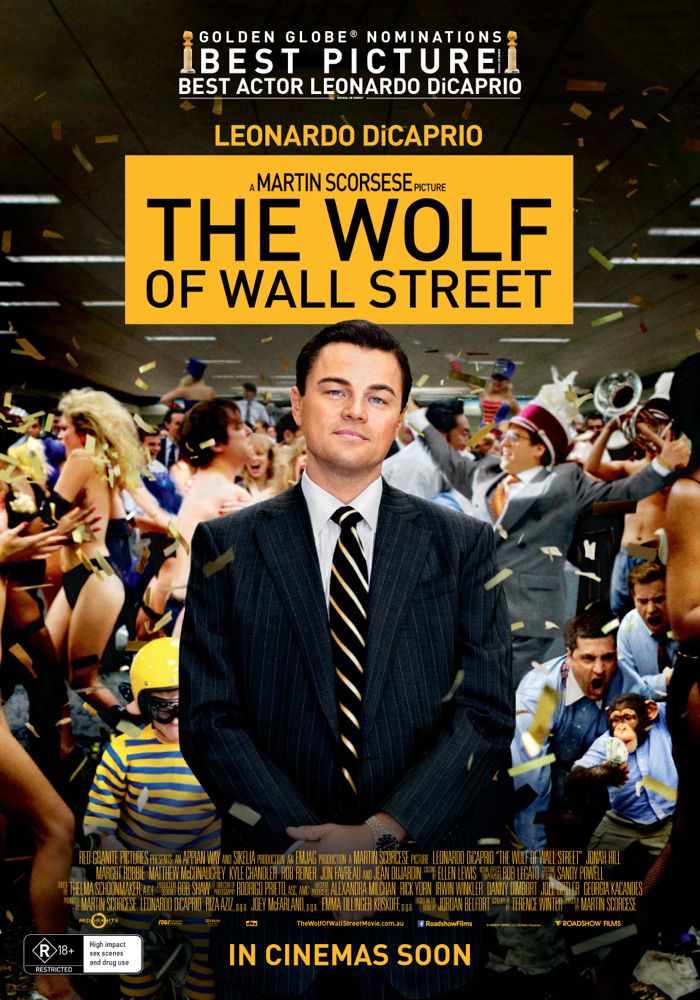

For a while, watching this movie, I had the idea that it was going to be a profound and important evisceration of the moral depravity of the Wall Street institutions that crashed the world economy in 2008 — a moral depravity at the heart of the American system.

It’s nothing of the sort. It posits the idea that there are elements within the American system determined to bring the morally depraved criminals on Wall Street to justice, and capable of doing so. In short, don’t worry too much about Wall Street criminality — the F. B. I. is on the case.

Ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha.

Martin Scorsese, once a fiercely independent filmmaker, has become an apologist for the plutocracy. Fuck him.

Click on the images to enlarge.

Why come down harder on Scorsese than on David Irving?

I come down pretty hard on David Irving, but the nearly universal hatred of him has tended to obscure some of his virtues. He’s also a patent scoundrel — not a great artist like Scorsese who’s sold out, a fact which the nearly universal admiration of him has tended to obscure. And my hatred of “The Wolf Of Wall Street” would never lead me to deny that parts of it are brilliantly made or that much of the acting, especially by DiCaprio, is brilliant. Belaboring the obvious or endorsing the common wisdom are tiresome exercises — what’s not so obvious or accepted makes for more enlightening contributions to the conversation of culture.

Who is the intended audience for the respective works?Whose ideas, if accepted, would do the most harm? Whose motives are the most unclean, if you will?

I tend to follow Hilberg in thinking that Irving and other holocaust deniers are not threatening, since their views can be demolished with facts. Hilberg even said that they were useful in motivating responsible historians to become more industrious and meticulous researchers. A popular movie which suggests that the government is hard at work trying to suppress Wall Street crime could lead to far worse consequences down the road — like another collapse of the world economy. The cleanliness of motives doesn’t see terribly relevant. There are some very nasty people encouraged by people like Irving but condemning Irving more than he’s already been condemned — suppressing more of his books and throwing him back in jail — won’t discourage them, because they’re nuts to begin with. Giving Irving his due as a researcher while still pointing out that he’s got a screw loose strikes me as the most effective way of dealing with him, and again, I think Hilberg would agree, because that’s basically what he did.

Evasive answer. You don’t ask if it’s credible to think people will believe the premise of a Hollywood comedy-drama, but you do deny that Irving could be believed. And so you do not address the question of what would happen if he were. The latter is the more serious question: how would Neo-Nazis and radical Islamists, for example, benefit from the views of Irving and other deniers? The Nazis were “nuts to begin with” but they were extremely effective in recruiting a nation to act on their beliefs. Why do you think Holocaust-denial is a crime in some places?

oops. ignore second to last posting. I hit “post comment” before I finished my sentence.

I have removed the premature post in question.

I dipped into Hilberg’s book last night and couldn’t put it down. Curiously, he offers an explanation for why the Nazis were able to “recruit” ordinary Germans to act on Nazi beliefs — because ordinary Germans already possessed those beliefs themselves and thus didn’t need to be recruited. They were already down with the program and just needed permission to do what they were inclined to do. To the degree that propaganda about it was needed, it only reinforced ideas that had been around for centuries.

It makes a lot of sense and in fact explains why no single directive or central planning bureau for the destruction of the Jews was needed. Irving uses this fact to argue that the destruction wasn’t national policy. Hilberg’s argument that it was national policy in every sense of the word is far more damning than the idea that the Nazis used rhetoric to sell the policy to credulous underlings.

My sense of why Hilberg thought it was counter-productive to get worked up about holocaust denial, much less make it a crime, was first that it imputed to the deniers too much credibility and power and second that it diverted attention from the real causes of the holocaust, which lay not in the provocative language of a few nuts but in the hearts of a whole people.

Hilberg argues that anti-Semitism was deeply embedded in the whole history of Western civilization but that it had always been tempered to a degree by counter impulses of humanity. The Nazis just decided to be done with “tempering”. This explains why so many people around the world — and not just Jews and “liberals” but even those temperamentally prejudiced against Jews — were shocked by the extreme nature of Nazi policy (even before the death camps,) and why the Jews were taken so totally by surprise when they realized that their usual methods of coping with persecution were not going to work with the Nazis.

It’s an elegant and profound analysis, I think, explaining both the historical continuum in which Nazism emerged and also its singularity.