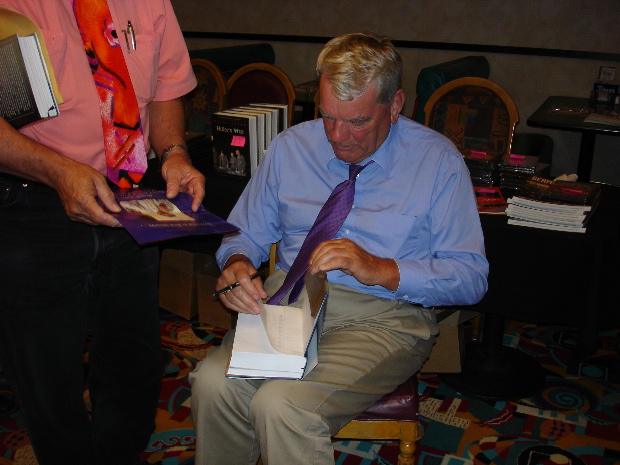

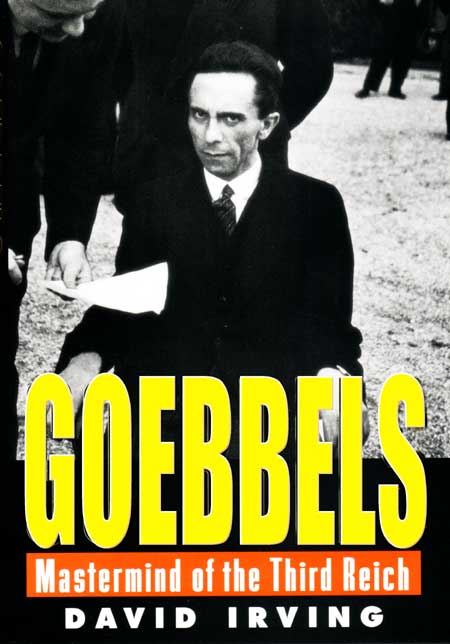

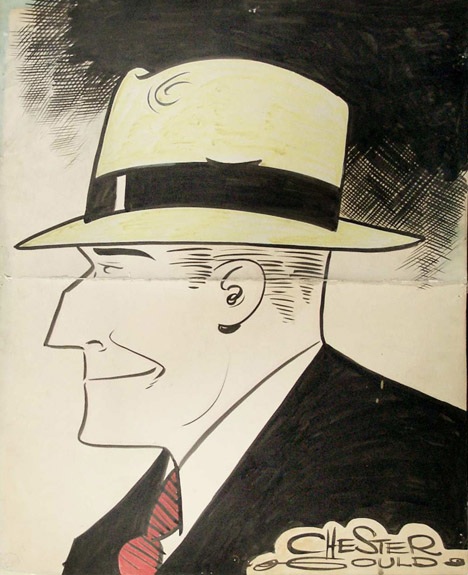

For many years historian David Irving (above) has been called a holocaust denier. In 1996 he brought a libel suit against historian Deborah Lipstadt for calling him that — and lost. So he is now officially a holocaust denier, at least in England.

It’s a fair verdict, depending on how you define holocaust denial. Irving accepts that atrocities were perpetrated against Jews by the Nazi regime on a mass scale, but not on the sale accepted by most historians. He also denies that the mass extermination of Jews was an official policy dictated by Hitler.

Irving contends that most deaths in concentration camps like Auschwitz (about 90% of them by his reckoning) were from “natural causes” — overwork, hunger and epidemics, especially towards the end of the war when all of Germany was suffering from shortages of food and medicines. He holds the Nazis criminally responsible for such deaths, given the conditions in the camps and the injustice of imprisoning people in them, but insists that only about 10% of those in the camps were deliberately executed by their captors.

He accepts that perhaps as many as one million Jews were deliberately executed in the conquered eastern territories by the Nazis, mostly by being lined up beside trenches and shot, but insists that these were ad hoc murders by local commanders overwhelmed by the number of Jewish refugees sent to them from Germany and other parts of the Greater Reich — not done on direct orders from Berlin.

Irving also argues for a kind of rough moral equivalence between Nazi atrocities and Allied atrocities. He believes that about 10,000 prisoners were deliberately murdered at Auschwitz, for example — which most historians consider a preposterously low figure — and points out that many times that number of German civilians were incinerated in single fire-bombing raids on German cities like Dresden (below).

There’s a good deal of sophistry in Irving’s arguments. The idea that a million people could be murdered and their bodies disposed of by Nazi functionaries, even in distant territories, without this being known in the highest circles in Berlin, without Hitler’s knowledge and at least tacit approval, violates common sense.

Irving’s contentions about the number of people who died in the camps, including the percentage of them that were deliberately murdered, have been vigorously contested by other historians. The facts on which the debate hinges are arcane and exceedingly unpleasant, involving such issues as the amount of fuel needed to cremate a corpse versus the amount of fuel available to the camps for the purpose.

I have read more on this subject than I should have and confess that I find the technical details involved beyond my competence to evaluate and beyond my spirit to contemplate further.

Whatever you think of Irving’s arguments, it’s clear that there’s an ominous agenda behind his views of the holocaust — a desire to minimize the evil of the Nazis and emphasize the evil of the Allies — which is distasteful, to say the least. But there’s an irony at the heart of Irving’s work. Even the Nazi murders and atrocities Irving does accept based on his archival research add up to . . . a holocaust, one of the greatest collective crimes ever perpetrated by a “civilized” nation, one that’s hardly mitigated by any atrocities that may have been perpetrated by those at war with Nazi Germany.

It’s an irony that seems to be totally lost on Irving as he goes about his smug revisionism, and speaks to his moral failings as a man. Only one or two million Jewish deaths can be attributed to the Nazis, he argues, not six. Only one or two million? You have to wonder how a man who thinks in terms like that can sleep at night.